Labor first announced the $3 million super tax way back in February 2023 yet debate about its merits has only started to heat up since the election.

The government wants to increase the rate of tax on earnings from 15% to 30% on the portion of superannuation balances of more than $3 million. Critics have homed in on two areas of the plan. First, the lack of indexation. Second, that the extra tax will also apply to unrealised capital gains.

The latter has proven controversial given it’s largely unprecedented globally, it’s likely to be messy and complex, and it will undoubtedly lead to unintended consequences when it comes to investment decisions. There have even been suggestions that those holding illiquid assets like farms with limited income or other assets may be unable to cover the additional tax impost on unrealised capital gains.

Ben Phillips and Richard Webster from the ANU’s Centre for Social Policy Research wanted to find out more about the income and wealth of those holding more than $3 million in super and whether they could absorb Labor’s new tax.

Here are the study’s key findings:

1. Around 87,000 individuals have super accounts with +$3 million.

That compares to Treasury’s figure of 80,000. The authors concede that at least on this number, Treasury is probably more accurate given it has access to tax data whereas they’ve relied on ABS survey-based estimates.

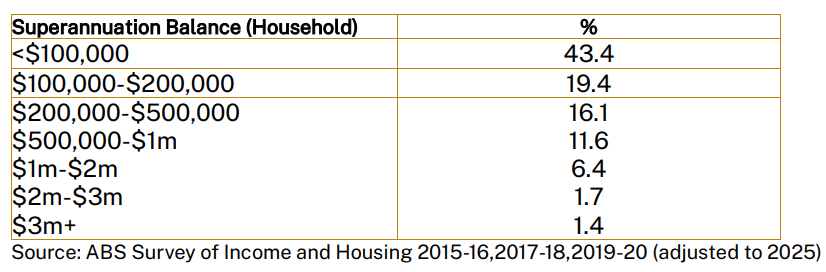

At a broader household level, only 1.4% of households have super balances above $3 million. Around 90% of households have super balances of less than $1 million and almost 20% have no super at all. And the average household super balance is $387,000 while the median balance is just $143,000.

Household superannuation balances, 2025

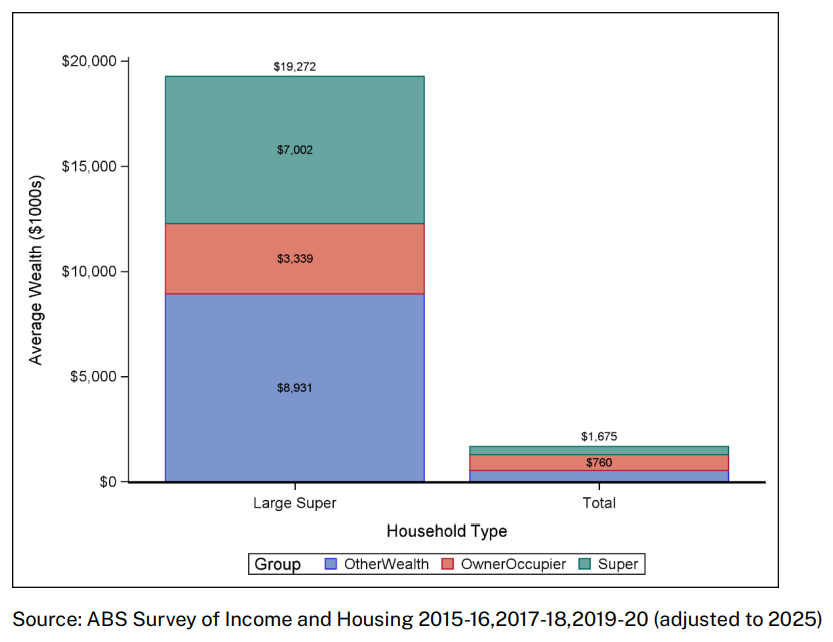

2. The average wealth of a household with at least one superannuation balance exceeding $3 million is more than $19 million.

Households with large super balances (with at least one member having +$3 million in super) have wealth averaging $19.3 million compared to $1.68 million for all households, or about 11.5x more.

The wealth isn’t just tied up in super. Of that $19.3 million, an average of $7 million is in super, $3.34 million is in owner occupied housing, and the rest is in other assets.

Total wealth and asset allocation by household type

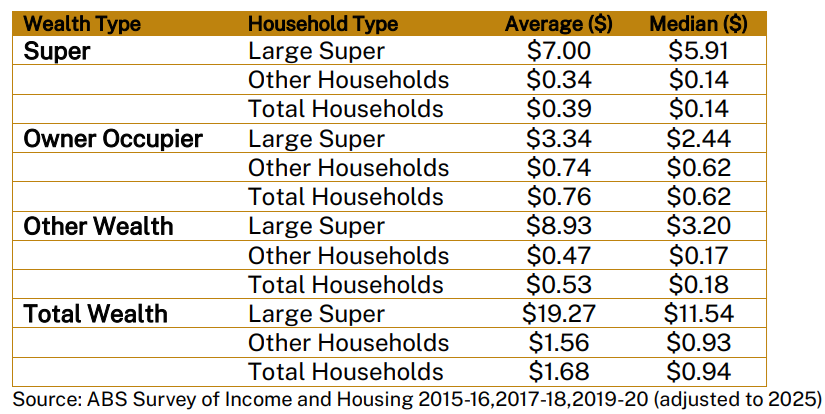

Total wealth and asset allocation by household type (in millions)

Note: ‘Large super’ = households where one person has a super balance >$3 million.

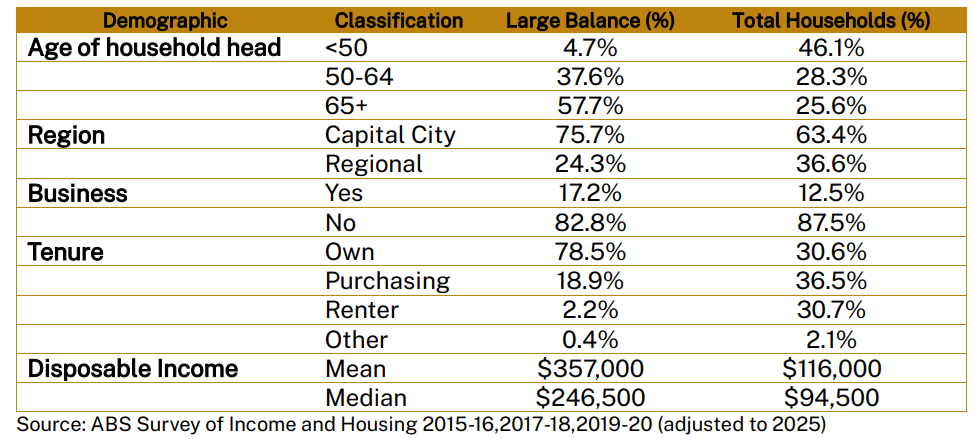

3. Most of those with +$3 million super balances are over 65 and own their house outright.

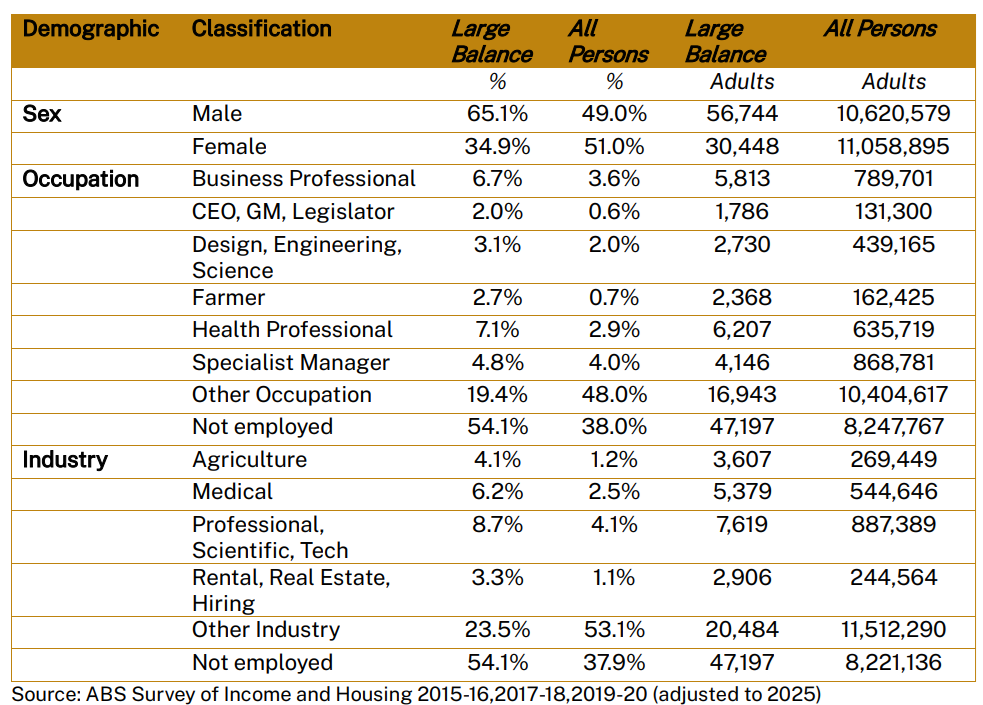

The study breaks down the demographic profiles of those with and without large super balances. For the 87,000 people with super balances of more than $3 million, it reveals:

- Three in four live in capital cities

- Two-thirds are over the age of 65

- More than half don’t work

- Of those who do work, most are in professional occupations

- Nearly eight in 10 own a house outright

- The average and median wealth levels are 12-13x that of the general population

Large superannuation and all household demographics

Large superannuation and all household demographics

Note: ‘Large super’ = households where one person has a super balance >$3 million.

4. Less than 1% of those with super balances will struggle to pay the tax on unrealised capital gains.

Using super and wealth data from the ABS, the study applies a crude test to estimate the number of people that may struggle to pay an unrealised capital gain tax liability.

The study models a scenario where an individual with $4 million in super records a 10% gain, and assuming no contributions or withdrawals, incurs an extra tax of about $19,000 (the tax liability would be 0.15 x (($4.4m - $3m) / $4.4m) x $400,000 = $19,091).

If that extra tax is more than 10% of the household’s disposable income and other wealth (wealth not in super or in the home), then that household fails the stress test.

In this case, the household could struggle to pay the tax if they are also unable to easily pay the tax from their super savings.

The research finds that only around 500 of the 87,000 individuals with super balances exceeding $3 million, or 0.6%, fail the stress test.

If the model assumes a 20% capital gain, 750 households or 0.9% fail the test.

The study concludes that “the impact of the extra tax would likely be relatively easily absorbed by the vast majority of impacted households.”

Taxing unrealised capital gains is still a bad idea

The study deliberately stays away from giving an opinion on whether taxing unrealised gains is good policy or not. I won’t be so shy.

Most people that I speak to are at least open to the idea of the super tax.

The lack of indexing is difficult to fathom though I suspect that the government didn’t want to include it in government budget forecasts heading into the election and may relent on the issue at some point soon.

The tax on unrealised capital gains is the bigger headscratcher. Why do it? To force people out of SMSFs? To punish farmers? I’m not sure. Whatever its motivations, it is messy, complex, and unnecessary.

It’s likely to result in those with super balances of more than $3 million diversifying at least part of their balances into other assets (is it contributing to the recent rise in house prices?). That will mean less revenue from the tax than the government estimates.

More broadly, time will tell whether the new rules improve fairness in the super system or decrease trust in super as a vehicle for retirement savings.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.