For the umpteenth time, tax reform is back on the agenda—this time as the centrepiece of Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ latest economic summit aimed at lifting productivity. He’s now positioning himself as a champion of efficiency and a warrior against red tape. But it’s hard to take that seriously when, according to recent reports, the Albanese government has added more than 5,000 new regulations in its first term alone. It’s a familiar pattern: a flurry of committees, consultations and reviews, with little real appetite for structural change.

We’ve been here before. The Henry Tax Review, delivered in 2009 and chaired by Treasury Secretary Ken Henry, was promoted as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to overhaul Australia’s tax system. The goal was to build a fairer, simpler, more sustainable framework for an ageing population and a globally competitive economy. But from the outset, its hands were tied. The GST was off-limits, as were tax-free super withdrawals after 60, and the politically sensitive excise duties on alcohol and tobacco – three of the most significant and contentious levers in the tax mix. That exclusion crippled its ability to deliver truly comprehensive reform.

Of its 138 recommendations, only a handful survived. The super guarantee was locked in to hit 12%. A mining tax limped through, so diluted it sparked industry fury and helped topple a PM. Small and medium businesses got a company tax cut, but the rest – think income tax tweaks, stamp duty reform, and family payment overhauls – were swept under the rug.

The problem is that any real tax changes are politically toxic. Just look at the current system. Once a person earns $135,000, they lose 39% of every extra dollar. That jumps to 47% after $190,000. These are hardly extravagant incomes by today’s standards, yet we’ve created a structure where effort is punished at the margin. It discourages productivity and encourages people to find ways to minimise tax – hardly a recipe for economic growth.

There’s been talk for years about eliminating the capital gains tax exemption on the family home, but that’s a practical impossibility. No government would dare touch it – and even if they tried, the wide disparity in house prices across Australia would make it unworkable.

Reducing the 50% capital gains tax discount is another idea that’s often floated, but implementing it is far from simple. Any change would have to start from a set date – but even before then, markets would be distorted. A rush of purchases would likely be followed by a slump, throwing long-term planning into chaos. And unless inflation is factored in, removing the discount would breach a fundamental tax principle: you shouldn’t tax inflationary gains.

Super is always in the firing line. There’s talk the government might impose a 15% tax on pension-phase accounts that are currently tax-free. But that would defeat the entire purpose of super: to provide a low- or zero-tax environment in retirement. A couple with $800,000 invested in their own names would pay no tax anyway, thanks to offsets and franking credits. If you tax their super, they’ll just pull the money out and invest it outside the system.

Then there are the perennial rumours about family trusts. Many small business owners—who are also among the country’s main wealth creators—rely on trusts for asset protection. If you’re a sole trader or in a partnership, your personal assets are on the line if things go bad. That’s why most use trusts or companies. A trust doesn’t pay tax—it distributes income to beneficiaries, who then pay at their marginal rates. Yes, trusts can offer tax advantages, but they’re modest. Distributions to minors are taxed at the top marginal rate above $416 a year. And with the 30% bracket now stretching to $135,000, there’s little point targeting trusts with new taxes—owners will simply shift distributions to wages.

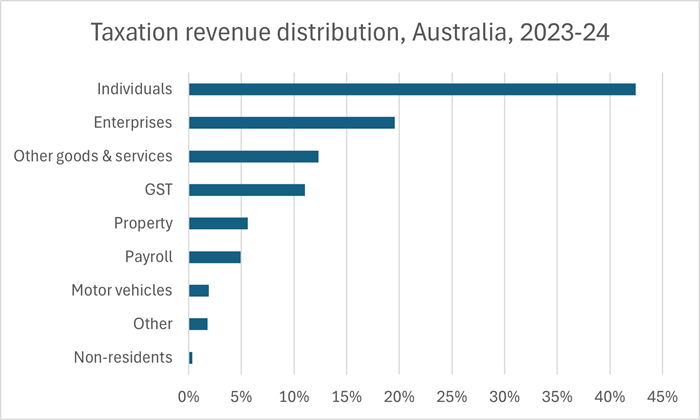

Source: Firstlinks, Australian Bureau of Statistics [www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/government/taxation-revenue-australia/2023-24]

If we’re serious about reform, the only practical solution is to lift the GST to 15% with no exemptions. That would hit the black economy hard and ensure retirees – who currently contribute very little – help cover the rising cost of services.

Of course, any GST increase will be slammed as regressive. But so are petrol taxes, liquor excise and cigarette duties – and no one seems to object to them. The strength of the GST is its efficiency. It’s almost impossible to avoid. It captures a broad slice of the cash economy, and while it does affect low-income earners, it hits big spenders hardest – those with the most disposable income.

Noel Whittaker is the author of Making Money Made Simple and numerous other books on personal finance. His advice is general in nature and readers should seek their own professional advice before making any financial decisions. Email: [email protected].