The Roman emperor Nero, apocryphally, fiddled while Rome burned in 64 AD.

Few politicians in modern times can play a violin or fiddle but they are very good at rhetoric, filibustering and back-flipping. And this explains why in Australia they consistently score so low on the Roy Morgan ethics and honesty ladder: indeed, below 15 points out of a hundred, sitting with union leaders, but above drug dealers, car salesmen and realtors. If that is any consolation.

The wasted tax enquiries and summits of recent years testify to the insincerity or lack of courage of governments since the Howard/Costello era.

Facts have rarely been put on the table for the voting population to get perspective, either historical or international. Vested interests, as usual, go as hard as they can to muster support for their rent-seeking, bleeding-heart platforms or political opportunism.

Voters should be advised or reminded that we are living beyond our means, and need to raise taxes - or cut welfare and support (political suicide) - to balance our budgets and arrest the growing national debt being left to our children. The public deserves perspective.

What are the realities?

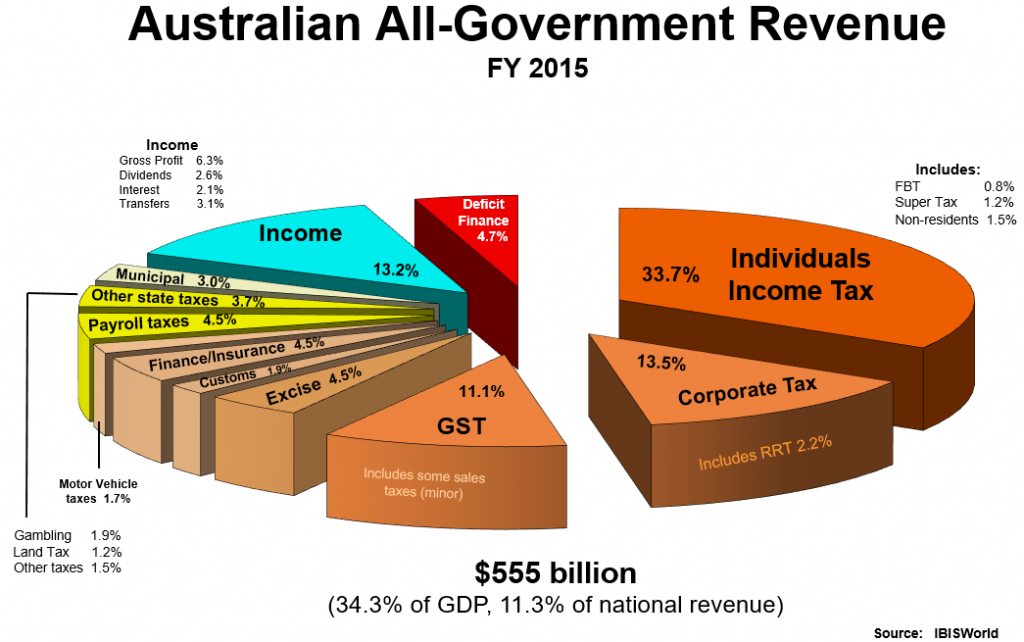

The first exhibit reveals that government at all three levels raised $555 billion in 2015, just over a third of the nation’s GDP. The vast majority of it is via taxes, supplemented by income from GBEs (government business enterprises) and borrowings for the deficit.

It is nearly three times the share of GDP as when the nation federated in 1901, but then and for decades later, helping the less fortunate was a case of charity and family or tribal support. There was no national defence force, no pensions for the olds, no unemployment relief, no free education, little health care, no support for industries nor many other support services which we take for granted today. And want to keep.

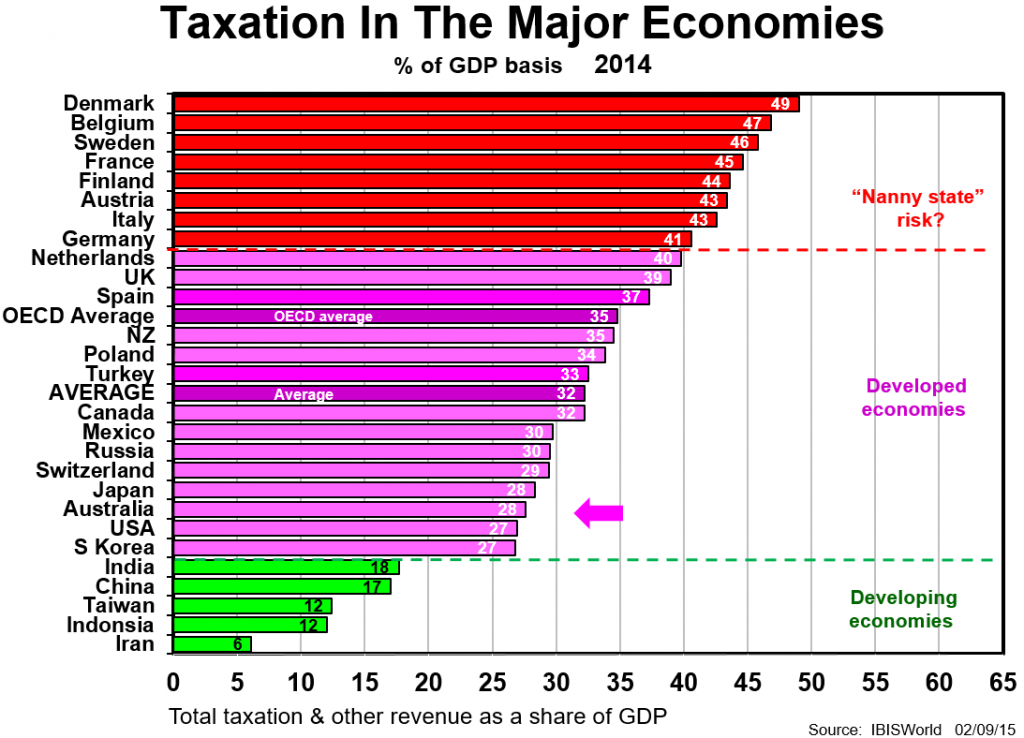

If anything, we could be regarded as a bit mean-spirited with a current level of taxation at 27.7% of GDP in 2015. This compares with over 30% not so long ago, and is far below the OECD average of 35% of GDP; but not as lavish as many so-called nanny-states at over 40%.

The mischievous, self-serving and fallacious argument about the damage done by an increase in the GST and removing current exemptions on food, education and health to fixed and low income earners is scaremongering. It ignores the accompanying protection to such vulnerable households that would be given by legislation: governments are loathe to commit electoral suicide when it comes to taxation reform. Pensioners and other disadvantaged individuals and households would be largely compensated.

So let’s turn to some of the myths and lies about our current taxation system.

Myth Number 1: We are highly taxed already

No, we are certainly not taxed highly by international standards, as seen in the second exhibit, and not by historical standards.

Let’s put the lie to the suggestion that we are highly-taxed or over-taxed once and for all.

Myth Number 2: Raising the GST is regressive

We are the lowest GST nation in the developed world at an effective average rate of 4½% on goods and services, given the aforementioned exemptions. This compares with an effective average rate of 14% in the OECD; over three times our rate. It is hardly an unprecedented or risky step to raise the level as a way of balancing our budget.

Leaving the nominal rate at 10% but removing exemptions from the present regime would in itself lead to a balanced budget, provide room for compensation of the low and fixed income sectors of our population, and allow for adjustment to the tax thresholds arising from bracket-creep.

Raising the level to 12.5%, again without exemptions, would create room for a number of other initiatives as well, such as substantive reduction in personal income tax scales; reduction in corporate tax levels; elimination of some state taxes (eg stamp duties, payroll tax), or at least most of them. Doable, one would think.

Myth Number 3: Our payroll taxes are a disincentive to employ more staff

There is always talk of getting rid of payroll taxes, they being one of the bêtes noire of business. However, by international standards, we are low down the ladder of those that have labour taxes. Even if we lump in super payments (although they are not a tax, like social security taxes in other countries) into labour taxes, we are just over half the OECD average.

Myth Number 4: Our corporate rate of tax is uncompetitive

There has been a more recent push to lower our corporate tax rate from 30% to, say, 25% (and lower the Small to Medium Enterprise tax rate of 28.5% as well).

But the Australian corporate tax rates are not really too far out of kilter, being close to the average of developed economies.

There is a case to lower the tax rate if it would lead to higher investment from retained profits, thereby creating growth and productivity in the economy. A 27.5% rate would be a good start.

Myth Number 5: The rich don’t pay enough taxes

One of the few ugly genes in the Australian ethos is envy and covetousness, in stark contrast to the aspirational genes in the USA. Fairness and equanimity is one thing – and we are good at those things by and large – but pulling down the ‘tall poppies’ is just plain silly.

The rich and well off, 40% of Australian households, pay the vast bulk of all taxes anyway, a stonking 87%! Some 60% of households pay less than 13% of all taxes. So, there is a lot of humbug and politicking in the area of who is copping the tax load. As usual, facts ruin a good story, or lie.

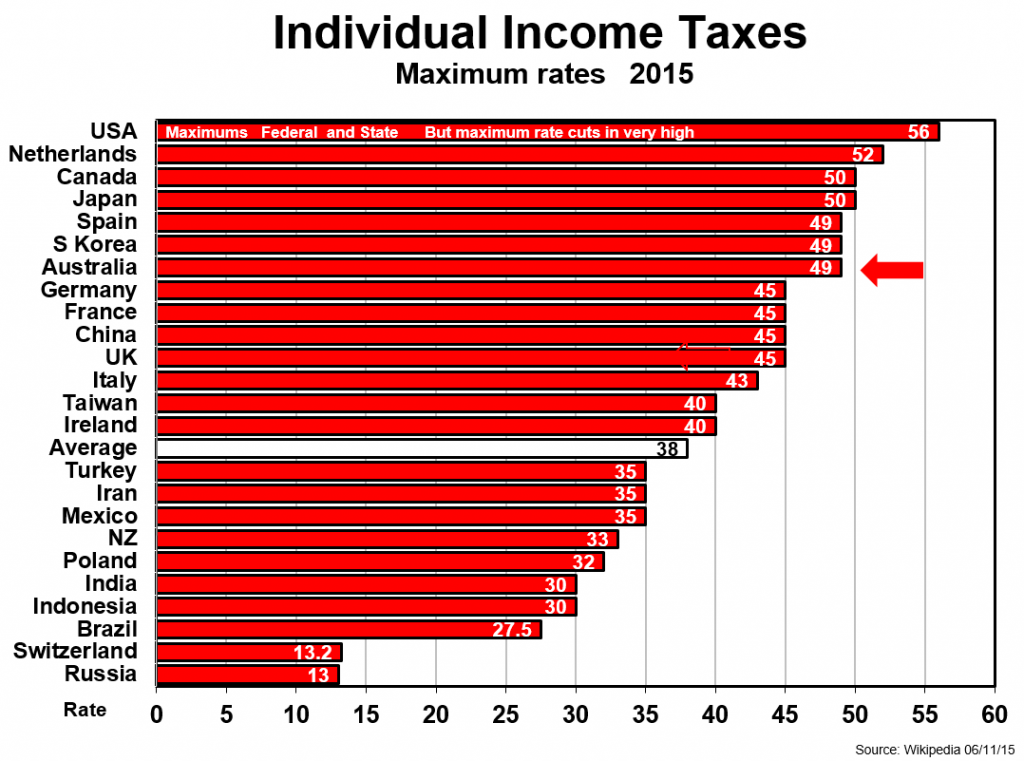

That said, bracket-creep in the individual income tax regime - the automatic follow-on from rising wages and inflation - is an issue that governments must, and do, address from time to time.

Our maximum individual income tax rate sits uncomfortably near the top of the international ladder as seen in the above chart, so this and other threshold rates do need addressing as part of a reform package. The Treasurer is addressing this issue in the government’s deliberations. We are taxing our citizens - rich and middle class alike - too highly. We should be lowering these direct taxes and replacing them with higher indirect taxes, especially the GST. The rich and well-off will pay much more of this GST as a result anyway, compared with the lower income households.

After all this, what should we do?

We are blessed with a very low national debt in 2016 that acts as a fiscal safeguard to our economy, but we need tax reform nevertheless. We are living beyond our means, primarily by not raising enough taxes by historical or international standards to cover spending, although that is not wildly out of control.

To try and save our way into balanced budgets is regressive, and unachievable anyway. We would lose services considered essential by 21st century standards, and equanimity in the community.

We should alter the mix of taxes in favour of the indirect (wealth spending) taxes to encourage savings, investment and productivity. The GST should be increased. Income taxes should be lowered. And the potentially disadvantaged poor and fixed income earners need to be compensated at the same time. All doable, with vision, courage and salesmanship.

Phil Ruthven is Founder of IBISWorld and is recognised as one of Australia’s foremost business strategists and futurists.