Investors are bombarded with tips on how to win in the stock market. Pick this stock; choose that stock. Follow this expert; follow that expert. Ride this new theme; ride that new theme.

There’s so much information out there that it can be confusing even for seasoned investors.

What often happens is that many investors don’t have a specific investment strategy or style for achieving their goals. That makes them vulnerable to following the latest stock fad or listening to the new hot tip from their local stockbroker.

And some investors do have a strategy, though not one that suits them. They may be a short-term trader who gets stressed out and that stress takes a toll on their investment results. Or they may be an investor in growth stocks but get queasy paying higher prices for these types of companies.

In my experience, it’s often best for investors to employ one strategy that suits them – and to stick to it. Doing this filters out a lot of market noise. It can make you focused and disciplined, and over time, more of an expert in your given strategy.

What are the best stock strategies to choose from? The following is a list of nine strategies that are tried and tested. And I’ve broken them down to those that will suit beginner, intermediate, and advanced investors.

Novice investors

1. A broad stock market ETF

I’ve started off with the simplest method. Broad market ETFs give investors exposure to large swaths of stock markets. They provide access to the best companies and a slice of the growing profits and dividends that they earn.

The strategy has proven itself over time. Equities have consistently outperformed other asset classes in the long term. And broad market ETFs have captured the gains in equities at minimal cost.

Industry titans including John Bogle and Warren Buffett have endorsed buying broad market ETFs.

This method suits beginner investors and those that don’t have the time or inclination to follow markets.

For the Australian market, the largest broad market ETFs include Vanguard’s Australian Shares ETF (ASX: VAS), Betashares’ Australia 200 ETF (ASX: A200), and iShares’ Core S&P/ASX 200 ETF (ASX: IOZ). For international markets, the best known ones are Vanguard’s MSCI Index International Shares ETF (ASX: VGS) and iShares’ S&P Global 100 ETF (ASX: IOO).

2. Growth at a reasonable price

Growth at a reasonable price, or GARP in industry parlance, encompasses many different investment strategies. For simplicity's sake, I’m going to endorse one particular strategy: buying blue chips with growing earnings and dividends at a reasonable price.

Why this strategy? First, buying blue chips is less risky than purchasing mid- or small-cap stocks. Second, those with growing earnings and dividends generally have better prospects than those that aren’t growing earnings or don’t have any earnings. Third, buying at a reasonable price ensures you don’t pay too much for companies and have a margin of safety if things go wrong.

The trick with GARP is to purchase companies that not only have historically grown earnings and dividends but will continue to do so. That can require research into both the business and the industry it operates in.

The other trick is to pay a reasonable price for the company. There are many ways to value stocks. For beginner investors, checking the price-to-earnings (PE) ratio of a company versus both the market and its industry is a good start.

For example, let’s take a well-known company such as Wesfarmers (ASX: WES). It owns well-love brands such as Bunnings, K-Mart, and Officeworks. It’s consistently grown earnings over time and the prospects look reasonable given its dominant market share in the hardware, discount department store, and office supply categories.

It’s priced at a 34x forward PE ratio, compared to the ASX 200’s forward PE ratio of 19x. That’s a steep premium and while it’s a quality company, the question is whether it warrants such a big premium.

You’ll also want to compare its price to other blue chip retailers such as Woolworths (ASX: WOW), Coles ASX: COL), and JB Hi-Fi (ASX: JBH), and see how it stacks up.

This type of exercise can at least give you an initial feeling about whether the price for Wesfarmers is reasonable or not.

The GARP method will suit investors who want to be more involved with their investing and the stocks they choose.

Intermediate investors

3. Founder-led companies

Research both in Australia and overseas shows that companies led by their founders generally outperform indices.

In Australia, fund manager, Blackwattle, did recent studies into the issue. They found that an equal-weighted portfolio of 50 founder-led companies on the ASX outperformed the ASX 300 by a whopping 18% a year in the decade to October 2024. The founder-led stocks included WiseTech, ResMed, Fortescue, Goodman Group, and Block/Square.

What explains the superior performance? Blackwattle believes founder-led companies have long-term thinking, higher investment in innovation, risk tolerance, strategic decision-making, and alignment.

Recent ructions with Mineral Resources and WiseTech show the risks with investing in founder-led companies. Founders in businesses can sometimes have unchecked power and that can lead to some of the problems that we’ve witnessed of late.

It’s a fine balance between having a leader who is driven, entrepreneurial, willing to lean into risk at the right times, and one who goes off the deep end!

4. Dogs of the Dow

Michael O’Higgins popularised an investment strategy of investing in underperforming companies named “Dogs of the Dow” in his 1991 book, Beating the Dow.

This approach is a deep value style of investing.

O’Higgins advocated buying the ten worst-performing stocks from the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) over the past 12 months at the beginning of the year but restricting the selection to those still paying a dividend.

The strategy has a long-term track record of beating the Dow index and it’s shown to work in Australia too.

However, this method is only suited to those with a certain psychological makeup – one that isn’t afraid to buy deeply unloved companies that have gone down significantly in price.

5. Low price-to-earnings/cashflow

US investment legends David Dreman and John Neff employed this strategy.

Neff managed Vanguard’s Windsor Fund for almost 30 years up to 1995. He achieved returns of 13.7% per annum, beating the S&P 500 by more than 3% a year.

He did it by buying beaten down stocks with low P/E ratios. He believed that as long as companies were fundamentally sound, a low P/E ratio meant they might be oversold and due for a rebound.

For example, Neff might look at a stock that was fundamentally sound and growing, and on a P/E of 10x versus a market P/E of 18. He might expect that company to grow earnings by 4% a year over the next four years, and for the stock’s P/E to rise toward the market multiple – let’s assume it gets to 15x by year four. If right, that would produce a gross return of 15% per annum over those four years.

It’s a conservative and even dull strategy that has proven itself over time.

It suits those investors who like a bargain, especially in the market.

6. Moats/compounders

A moat strategy involves buying great businesses at discounts to what they’re worth. This sounds like the GARP method mentioned above, though there are some different attributes.

Warren Buffett popularized the concept of buying moats. A moat is a sustainable competitive advantage. In capitalist societies, competition is the biggest threat to a company’s profits and returns. If a business has a competitive edge over industry rivals, it has the potential to earn excess returns.

Firstlinks’ parent, Morningstar, took Buffett’s concept and expanded it into an entire industry. Morningstar now has a moat rating for each of the 1,600 stocks that it covers globally.

What types of moats are there? Morningstar categorises five sources of moats:

- Network effect. A network effect occurs when the value of a company’s goods or services increase for both new and existing users as more people use them. It’s often found in technology enabled services such as social media, payment platforms, communications platforms, and e-commerce.

- Intangible assets. Investors often focus on tangible assets that are reflected on the balance sheet. However, just because something can’t be seen and quantified doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable. Patents, brands, regulatory licenses, and other intangible assets can prevent competitors from duplicating a company’s products or allow the company to charge higher prices.

- Cost advantage. Firms with a structural cost advantage can either undercut competitors on price while earning similar margins, or they can charge market-level prices while earning relatively high margins. In general, cost advantages stem from scale from firms that can spread their fixed costs over huge customer bases.

- Switching costs. When it would be too expensive or troublesome to stop using a company’s products or services, that indicates pricing power. For some goods and services, it is easy to switch to a competing product. For commonly purchased items competing products may simply be a shelf away.

- Efficient scale. When a niche market is effectively served by one or a handful of companies, efficient scale may be present because it is not worth it for competitors to enter the market given the small number of customers.

This can be a case where a pharmaceutical company has developed an effective treatment for a relatively small number of patients afflicted with a disease or where an expensive piece of infrastructure supports a targeted market like a railroad.

The moat strategy is suited to those investors who are willing to dig deep into industry and stock research.

Advanced investors

7. Dumpster diving

This strategy is like Dogs of the Dow though it requires even more fortitude and is therefore best used by advanced investors.

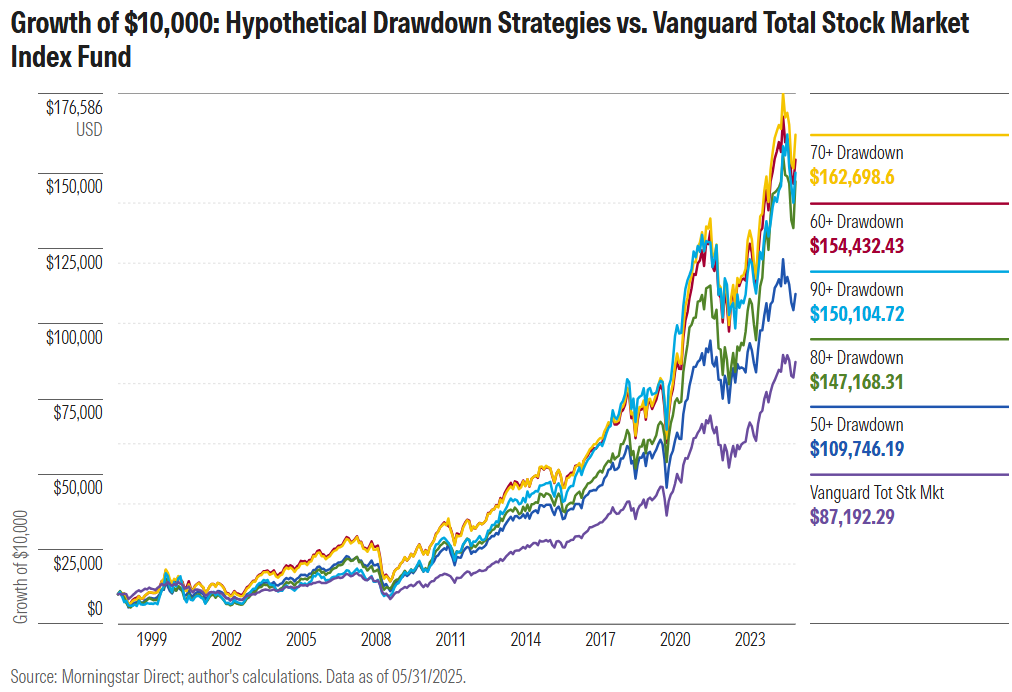

In an article in Firstlinks last week, Jeffrey Ptak investigated the strategy of buying and holding stocks after they’d gotten crushed. He tracked buying companies after:

50% or deeper drawdowns

60% or deeper drawdowns

70% or deeper drawdowns

80% or deeper drawdowns

90% or deeper drawdowns

Ptak found that all five strategies handily beat a broad market index fund in the US.

The catch is the strategy comes with higher volatility. That volatility will turn many off, though it’s an opportunity for an enterprising investor.

8. Factors

There are lots of quantitative shops that employ strategies based around ‘factors’. The factors include things such as momentum, quality, value and size.

For instance, momentum has shown to consistently outperform over time. It capitalises on the tendency of stocks that have recently performed well to continue outperforming. Put simply, “winners keep on winning” for a certain period.

Suffice to say, this is a sophisticated method only suited to highly advanced investors. However, there are ways to get exposure to factor investing via ETFs such as Betashares’ Australian Momentum ETF (ASX: MTUM) and VanEck’s MSCI International Quality ETF (ASX: QUAL).

9. Arbitrage

Arbitrage is a strategy that involves exploiting price differences for the same asset in different markets or locations to generate a risk-free profit. It works by simultaneously buying an asset in one market where it's priced lower and selling it in another where the price is higher.

There are simpler ways to use arbitrage too. For instance, buying a Listed Investment Company (LIC) at a 20% discount to its net assets is a form of arbitrage.

So is buying a company with net assets at a premium above the current share price.

Warren Buffett used arbitrage to great effect early in his career before taking over Berkshire Hathaway.

Summing up

Obviously, this isn’t a complete list of strategies. I’ve tried to cover the main ones which have been consistently successful.

The best investment strategy for you will depend on your age, background, experience, and risk tolerance. Please get advice if you need it.

Disclosure: Vanguard and VanEck are Firstlinks sponsors.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.