The federal election has been run and won, and many are asking the question as to why the polls did not predict Labor’s thumping win. A minority Labor government was the popular pollsters’ outcome, or a slender Labor majority at best.

But Labor trounced the Coalition with 91 seats won to 42 at the time of writing, to now take up sixty per cent of the lower house chamber. And it achieved this with only a little more than a third of the primary vote. In fact its primary vote was up just two percentage points from its 2022 win, to an underwhelming 34.7%, yet it has added 14 seats to its previous majority.

Compare this to Julia Gillard’s 2010 38.0% first preference vote, which only secured minority government. Or to Tony Abbott’s emphatic majority in 2013, requiring a significant 45.6% primary vote to win 90 seats. There is a clear upward trend in the ratio of seats won to primary vote, for the victor.

And with the Coalition’s share of the primary vote a clear rejection at just 32.2%, support for the two major parties is plummeting.

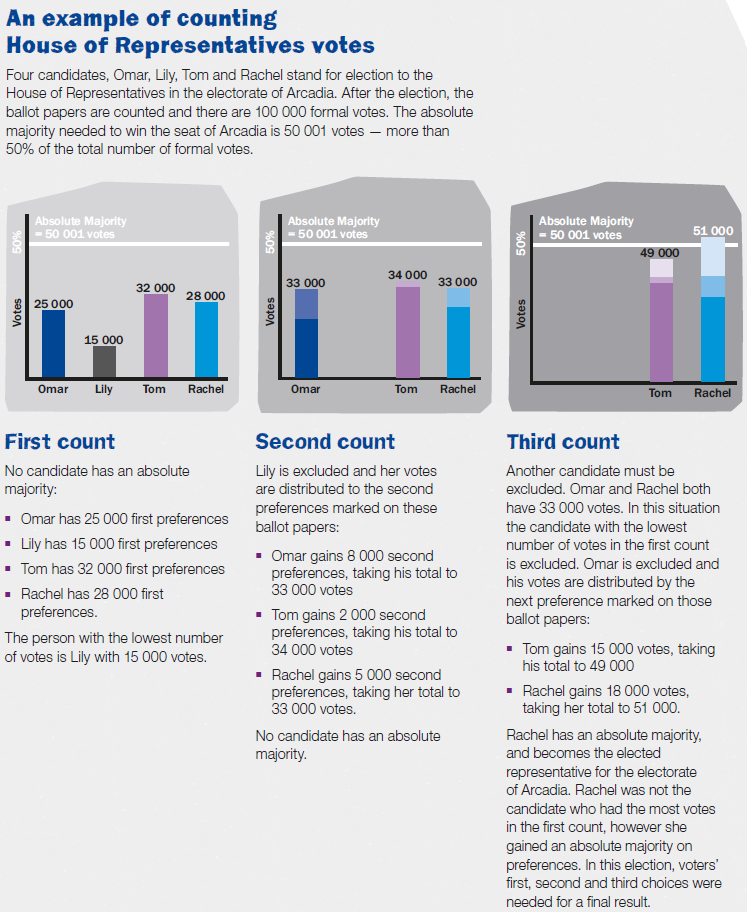

We also saw at this election, 138 of the 150 seats decided by preferences, including 15 seats that flipped on preferences after being behind on the primary vote. That, with the Labor two-party-preferred vote a whopping 20 percentage points up on its primary vote to 54.9%, reveals the extent to which preference votes contributed to the Coalition rout.

The significance of preference vote flows from minor parties and independent candidates is now more pronounced than ever. Which certainly creates havoc for pollsters. Trying to predict outcomes from national primary vote swings is becoming increasingly more difficult.

The problem is, polls focus on primary votes. But if future polling is to become more accurate, it needs to be recognised that preferences decide outcomes today, and polling methodologies must evolve accordingly.

Source: Australian Electoral Commission

But preference flows are not linear, and can vary significantly between electorates depending on the candidate and party profile. Which means a lack of data and modelling to accurately forecast vote flows. Unless more sophistication is introduced into the polling process, we should continue to expect the unexpected in future elections.

The fact that Labor was able to secure its huge majority with just over a third of the primary vote, highlights its ability to attract second, third, and lower order preference votes. And being able to jump over leading candidates after primary votes, including in Peter Dutton’s own seat of Dickson, displays a unique preference effect whereby the 'least disliked' candidate can prevail over the 'most liked'.

One interpretation of Labor’s low primary vote converting to a significant two-party-preferred result, is that a broad left of centre bloc exists in the electorate after distributing preferences. Differing political parties and groups exist because of different ideologies and values at a primary level, but can be aligned at higher levels on shared ideologies. And this election result reflects a more substantial alignment on the left side of politics via Greens, independents, and minor party preference flows.

This is the uniting effect of preferential voting: the bringing together of entities on a similar ideological page. Resulting this time in not just a Labor victory, but also a shift in aggregate voter sentiment on the political spectrum.

For the Coalition, the implications of the election results are such that it must shore up its base and lift its primary support. And at the same time appeal beyond its base to strengthen the preference equation. The challenge will be to determine to what extent it must pitch a more centrist approach to raise its competitiveness in a preferential voting system, without compromising its core political values.

A competitive opposition is essential for a healthy democracy to keep the government of the day in check, and be ready to step in as an alternative government.

For Labor, even with a supersized majority, it must not stray too far from centrist politics lest it weakens the majority bloc it heads up that has coalesced under preference votes.

The merits or otherwise of our preferential voting system have long been debated. The vagaries, challenges, and issues it throws at pollsters, voters, and political entities are intriguing, but must be adapted to, because it has been part of our voting system for a long time now, and it isn’t going away any time soon.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary.