Active fund managers have been copping it in recent years. On the one hand, passive funds have attracted huge swathes of money by offering investors a low cost and convenient way to access markets. And on the other, the growth in private investment has lured investors with the potential for outperformance with lower volatility, albeit with high fees attached. With their relatively large fees and mediocre performance, active funds have been caught in the middle and it hasn’t been pretty.

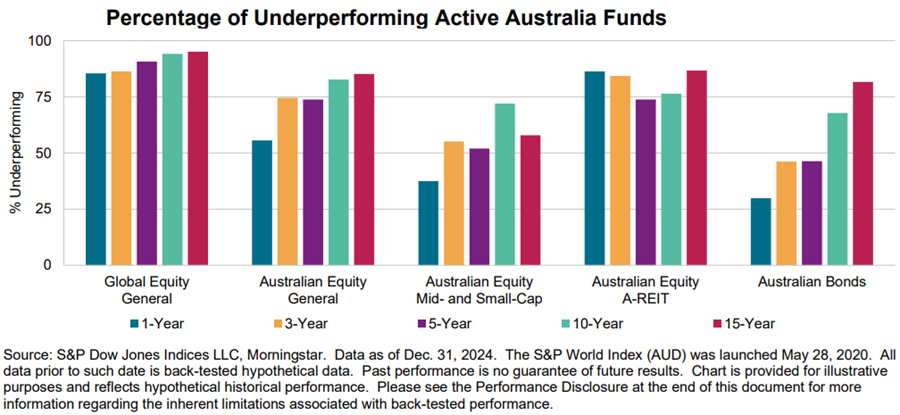

The above chart captures the poor performance of active managers. In 2024, 56% of Australian equity funds underperformed. Over the past 15 years, it’s been 85%. Global equity funds have fared even worse.

Australian mid and small cap equities funds and Australian bond managers did better in 2024, though their numbers are less impressive over longer periods.

Given all this, why would the average investor bother with active funds? Here are three reasons:

- The tide may be about to turn for these funds. That’s because two of the key trends of the past decade - the crowding into mega caps and low market volatility – are possibly reversing, which could be a boon for active funds.

- Even without this, there are still a lot of good fund managers, especially in the mid and small cap stock space, who have a consistent track record of outperformance.

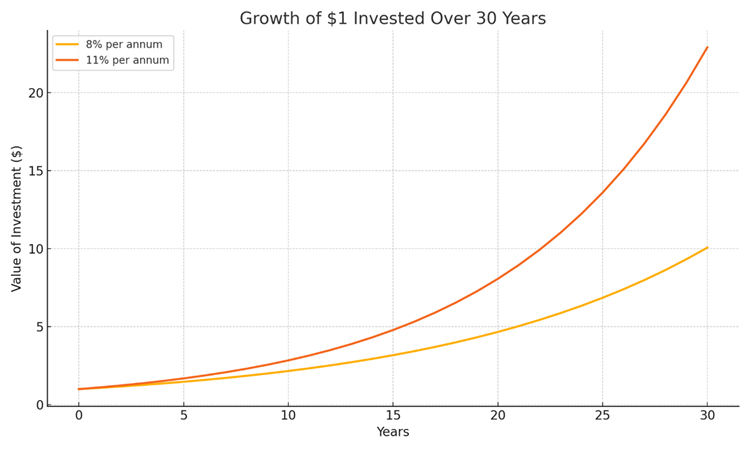

- Finding a good fund manager can make a big difference to a portfolio. The chart below shows a hypothetical example of what 3% outperformance from a fund can do in the long-term.

Source: Firstlinks, ChatGPT.

How to identify the best managers

So, how to identify active funds that will deliver for your portfolio? Here are the key traits that I look for:

1. A track record over +10 years

For me, a track record of outperformance is critical, and it needs to be judged over a long timeframe. The longer the better. Why? Because funds should be assessed over several business and market cycles.

For example, momentum and growth stocks have dominated over the past 10 years, while value stocks have lagged. Any momentum or growth fund that hasn’t outperformed in this environment has failed miserably. Conversely, any value-style fund that has managed to outperform has done a terrific job.

A longer track record allows for a more thorough assessment of a fund’s performance across different market environments.

2. Exceptional individuals/small team

In my experience, the best funds often have small teams. Larger teams can lead to there being “too many chefs in the kitchen.”

That doesn’t mean larger teams can’t work. Some mega global managers have mastered the art of teamwork and funds management.

In my experience though, they’re the exception to the rule.

3. An identifiable philosophy/process

Is a fund’s philosophy understandable? Has the philosophy and process been consistent over time?

A fund may have a great track record, but if I’m not comfortable with its philosophy and process, I generally walk away.

For example, I’ve never invested in well-known fund manager, Cooper Investors, because I’ve never understood their idea of finding ‘value latency’ in stocks to outperform over time.

I missed out by not investing with this exceptional manager, but I’m ok with that.

4. Manageable fund size

Size is the enemy of fund performance.

There are many stories of funds which perform well, win awards and get loads of media coverage, resulting in a surge of fund inflows, only for performance to then fade, with money quickly heading out the door.

Look up Neil Woodford in the UK or Bruce Berkowitz in the US. And there are plenty of Australian examples too.

That’s why I prefer to invest in funds that don’t get too big. Those that prioritise performance and clients over fees.

5. Low profile preferred

I prefer a low-profile fund over a high profile one. Part of the reason is that it can prevent fund size from becoming an issue. The bigger reason is that I like managers who focus on investing rather than marketing.

It’s why fund managers farming out back-office administration and marketing to the likes of Pinnacle and GSFM (both sponsors) makes sense for fund managers. The managers can get on with the job of investing money rather than worrying about the hundreds of other tasks needed to run a funds management firm.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, though I’ve neglected to mention one thing and that’s fees. That’s because I think good funds are worth paying up for.

How to spot red flags in funds

How can you avoid funds that end up being duds? Here are five red flags that I look out for:

1. Massive outperformance

If a fund shoots the lights out, it can be a red flag. The fund may have had a certain style that gained favour. Or they could have run a concentrated portfolio where huge gains came from a few stocks. Or they could have employed leverage to juice returns.

Think of “The Big Short” stars such as John Paulson and Michael Burry, who took huge bets shorting credit default swaps prior to the GFC, yet after those life-changing gains their track records since have been found wanting.

2. Changing of investment style/process

If a fund changes its investment style, philosophy, or process, it can be a big red flag. It can mean the fund is struggling and is trying to dig itself out of a hole. Unfortunately, that rarely works.

3. Big increase in funds under management

As mentioned above, a sudden, large influx of money into a fund can spell trouble for future performance.

4. Inappropriate benchmarking of returns

I used to see it more, but there have been Australian equity funds that benchmark their performance against the cash rate, rather than the ASX 200 or 300. If I see this from a fund, I steer well clear of it.

More often, I’ve seen funds switch the benchmarks that they measure their performance against. They may swap the ASX 200 for the ASX 300 or the ASX All Ordinaries index. That’s another red flag for me.

5. Lack of transparency on returns

I don’t like funds that only show ‘gross returns’ rather than ‘net returns’. Investors don’t pocket gross returns, they pocket net returns, and it should be disclosed as such.

Another red flag for me is funds that include their returns at a prior firm. For instance, a boutique firm may quote returns not only at the boutique but from when the same team worked at a larger firm prior to that. It’s a perfectly legal practice though I'm not a fan.

Let me know your views on active funds and whether I’ve missed any key points.

(Full disclosure: Firstlinks has a large group of sponsors, many of whom are fund managers. Also, our parent company, Morningstar, does fund manager ratings for a living, based around its five-pillar framework: process, performance, people, parent, and price (the ‘5’Ps’). Therefore, it’s a sensitive topic and I’m bound to get hate mail. The views expressed are mine alone and based on my time as a former fund manager, stockbroking research analyst, and now Firstlinks editor.)

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.