The super tax and its intricacies have rightly generated heated debate, though I think it’s time to ask some deeper questions:

Why did the Government choose to introduce this tax?

Why is the Government refusing to budge on aspects of the tax despite an intense public backlash?

What are the circumstances that allowed them to propose this tax?

Why are many wealthy people ok with the tax, albeit critical of it being applied to unrealised capital gains and there being no indexing?

Why have the merits of Baby Boomer wealth been at the forefront of the tax debate?

A simple answer to these questions would be that the tax can be put down to the Government needing to raise revenue and a small group of wealthy people being easy targets. I think it’s more complicated than that, and this will look at the key factors behind the policy as well as why more taxes on the rich are likely in future.

The young have pitchforks

Since the 1980s, Australia has adopted the deregulated, capitalist model of other developed countries such as the US and Britain. It’s resulted in us becoming a lot wealthier.

Since the GFC though, that model appears to have run out of steam. Economic growth and wages have stagnated, while asset prices have continued to boom. Those who’ve owned assets have been beneficiaries and those who haven’t have been left behind.

How has this happened? At least some of the blame can be apportioned to successive Governments being unwilling to address the key factors underlying economic weakness. They’ve been put into the too-hard basket.

Instead, Governments of both sides have been too happy to pump up asset prices to give the appearance of increasing wealth and collecting votes from asset owners along the way.

It’s led to an increasingly financialized world where Governments pile on more and more debt to keep asset prices inflated. Any economic downturn that threatens ever-rising asset prices is met with more Government stimulus and debt.

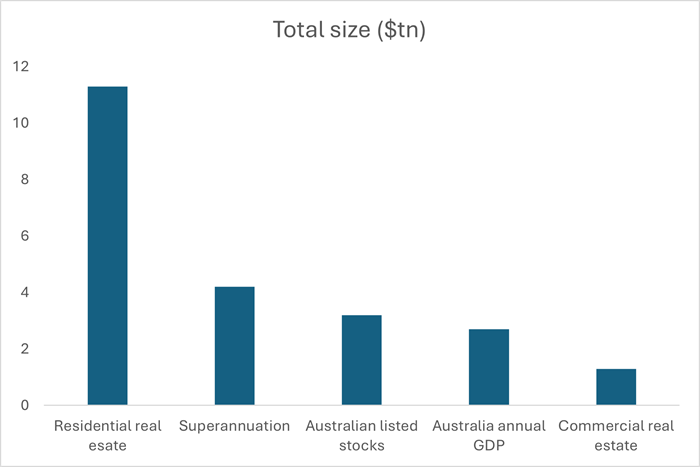

Sources: CoreLogic, APRA, RBA

The above chart is the poster child of this increasingly financialized world. Assets dwarf real economic activity. And things like housing, a largely unproductive asset class, crowds out investment in more productive areas.

Who’s benefited most from this situation? Undoubtedly, those who are retired or are retiring – largely, the Baby Boomer generation.

And who have been the biggest losers? The younger generations.

In this context, it’s hardly surprising that the young are revolting at the ballot box, turning away from the major political parties who’ve prioritised asset inflation over real economic growth.

And it’s also hardly surprising that the young support increasing taxes on those who’ve profited most from the asset gains.

Stretched Government budget

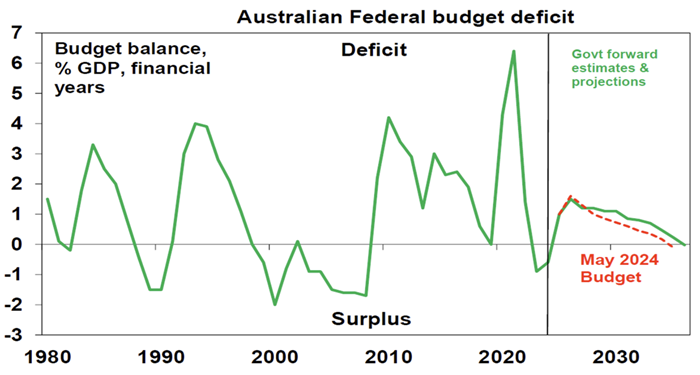

The state of the federal budget has been another factor behind the super tax. The Government is forecasting deficits for much of the next decade, and their predictions are almost certainly underplaying the extent of them.

Source: AMP’s Shane Oliver

Total public sector expenses grew by 9% last financial year, and that growth is unlikely to decline much in years to come. Many commentators put the blame on the Labor Government though that oversimplifies it because much of the spending looks structural rather than cyclical.

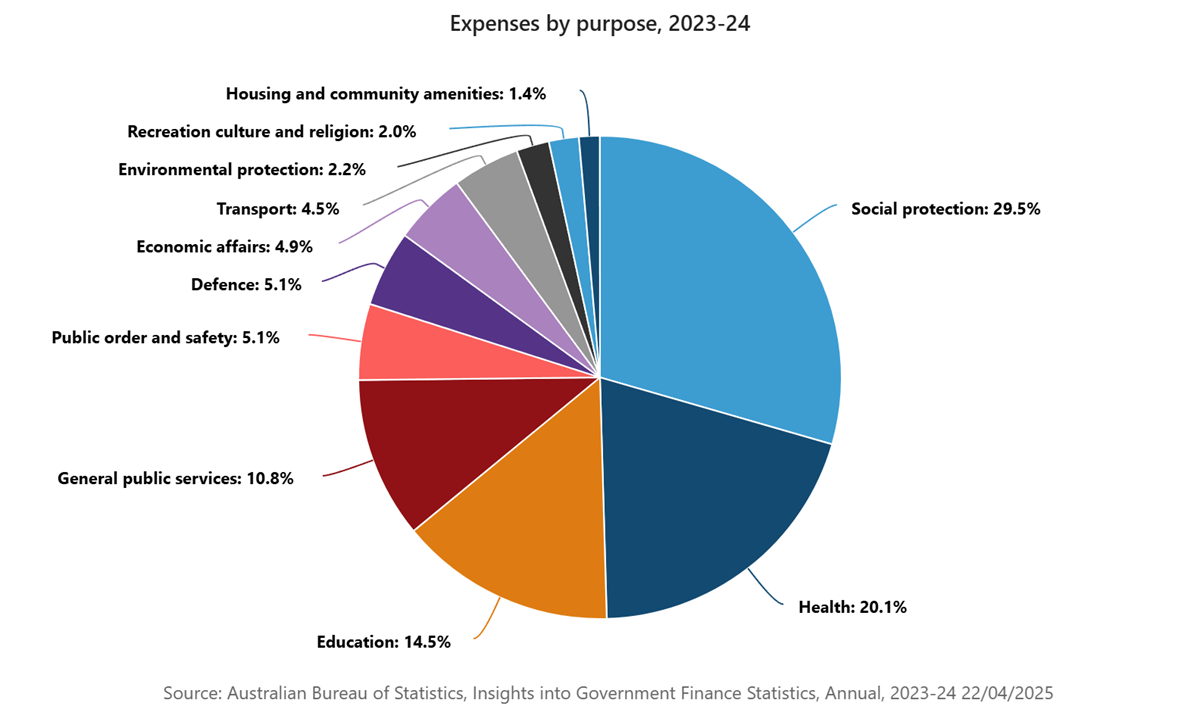

Breaking down the Government expenses, almost a third goes towards ‘social protection’. It entails Government payments for old age, disability, and family and children. This category of expenses increased 14% in 2024, thanks to higher Aged Care pensions and subsidies, NDIS costs, and childcare subsidies.

The second-largest expense category is health, which involves hospital services and community health services.

The third-largest expense is education, both school and tertiary. That’s followed by ‘general public services’, encompassing debt transactions and interest costs, and then public safety and defence.

Now, it’s hard to see the growth in the four largest expense categories decreasing much. An ageing population means more money going towards Aged Care and hospitals. NDIS seems to have a life of its own and while growth may slow, it’s an expense that almost certainly won’t go down. Meanwhile, education costs continue to increase well above the inflation rate and there’s no sign of that slowing down.

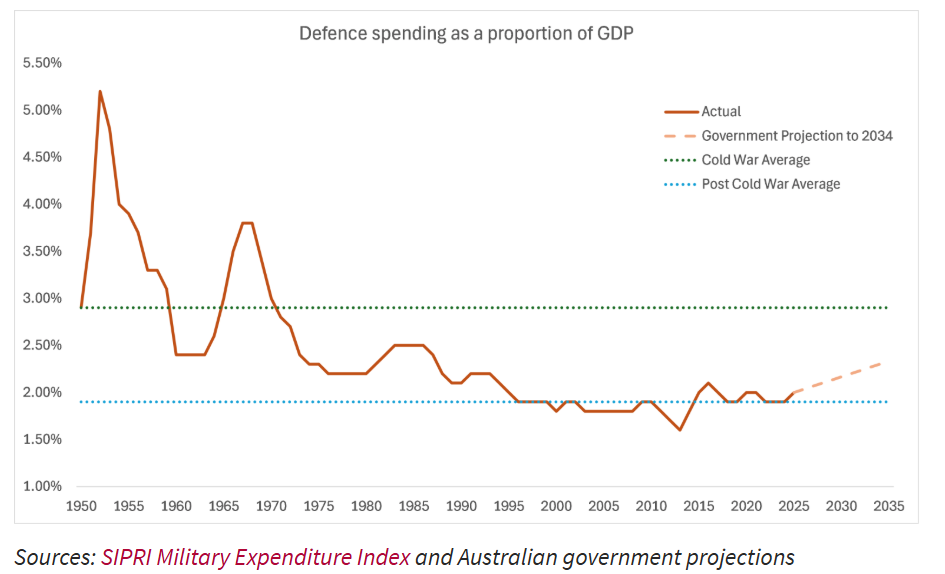

Defence is one to keep an eye on as Australia only spends about 2% of its GDP on defence. This is low compared to most of our history. And keep in mind that Donald Trump is pushing NATO allies to up defence spending from 2% of GDP to 5%.

While Government expenses continue to grow, income will be harder to find. Most Government revenue is raised through tax, and most of that comes from personal and corporate tax. Personal tax has been strong of late due to low unemployment and strong migration. These two drivers are expected to fade.

Meantime, corporate taxes are sputtering along as economic growth stagnates. Unless the economy revives, corporate taxes will struggle to grow much.

Whichever way you look at it, the odds are that budget deficits will increase in coming years. Potentially, by a lot.

The Government will need to fund these deficits. There are three main ways that it can do this: raise taxes, increase debt, or cut expenses.

As mentioned, cutting expenses will be hard to do. Increasing debt is an option that will almost certainly be taken up given Australia’s still relatively low debt to GDP. The other option is taxes, which is another lever that the Government will turn too.

Now, you may think that all of this is blown out of proportion given projected budget deficits are still relatively small and Government debts are low. But unlike periods before where deficits were higher, today we have low economic growth, high Government spending from an ageing population, and greater wealth inequality. Combined they will put further strain on the budget.

Tax concessions are prime targets

Another reason behind the super tax may be that our tax system seems to skew towards asset owners over income earners. Personal income taxes and savings are taxed at high rates, while many investments are not.

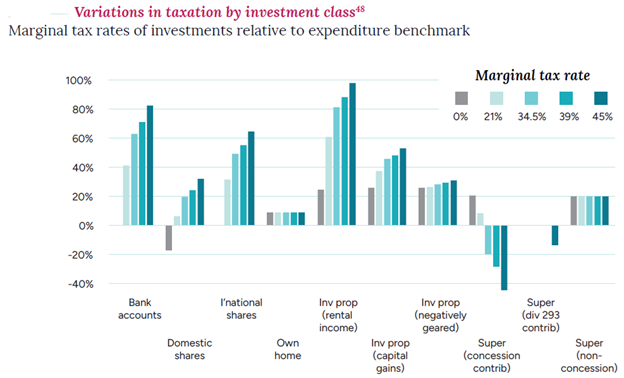

Source: Peter Varela et al 2020

Admittedly, this chart is from 2020 and outdated, though I haven’t been able to find an updated one. Nonetheless, it gives a flavour of the marginal tax rates of various investment versus expenditure.

What stands out are the relatively low tax rates on super, homes, and negatively geared property.

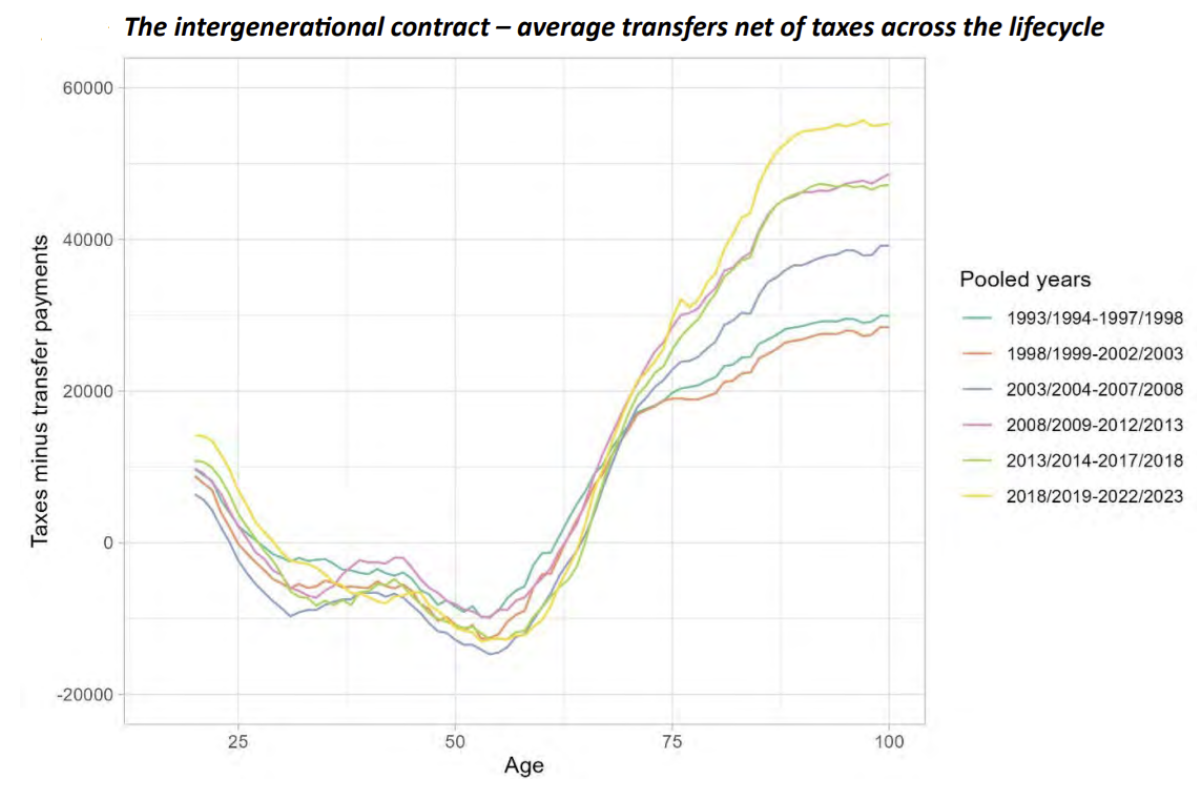

A recent academic paper from the ANU, ‘Measuring the changing size of intergenerational transfers in the Australian tax and transfer system’, gives further insights into who benefits most from the current tax system.

It found that the tax and transfer system had been more generous to older Australians than younger ones.

It said government spending on older people, including the age pension, aged care and health care, had increased significantly in real, per-person terms over time. By contrast, net spending on younger households had remained relatively constant.

And the figures weren’t distorted by an ageing population as they were measured on a per capita basis.

The rich are open (somewhat) to higher taxes

A remarkable aspect of the super tax debate is that there’s been less disagreement about the imposition of the super tax than about the lack of indexing and inclusion of unrealized asset gains. From comments in Firstlinks and elsewhere, it seems a reasonable proportion of the wealthy support the new tax.

How did it come to this? After all, these people played by the rules and now those rules are changing and upending their lifelong savings.

Demographer Neil Howe may offer insights into how this happened. Howe is well known for authoring a 1997 book with William Strauss called The Fourth Turning. An analysis of generation-driven historical cycles, the book predicted that a period of political, economic, and social upheaval would rattle the US midway through the first decade of the 2000s, culminating in an acute crisis or series of crises in or around the 2020s.

When the financial crisis hit in 2008, the book was hailed for predicting that event, and it’s since gone on to achieve cult status and even served as the inspiration for a Pulitzer-nominated 2019 play, Heroes of the Fourth Turning.

Howe has written a recent book, The Fourth Turning is Here, where he outlines that a crisis period is upon us where the old economic and social order will be ripped up as Millennials rise to power.

I won’t go into detail about Howe’s generational theory, suffice to say that I think it’s a stretch to organize history along generational lines and his forecasts are vague enough to get many people to believe in them.

That said, Howe’s views on how Baby Boomers will respond as power shifts to younger generations are intriguing:

“With the Crisis itself placing new burdens on the lives of younger generations, Boomers will choose to retain their moral authority by arguing—uncharacteristically—to impose sacrifices on themselves and other older Americans for the sake of their community. This will seem less surprising in the context of their own families; most Boomers today are already providing generously, sometimes more generously than they can afford, for their own children and grandchildren. But it will seem more surprising when they do so in the context of the national community and support tax and benefit changes that hit their own ranks the hardest. But the logic will be inexorable. The young, acting on behalf of the community at a time of peril, will now have a much better claim on resources than they do. So Boomers will let go.

“Everything will be on the table. A persuasive case will be made for taxing consumption and assets along with meaningful inheritance taxes, since these draw the most revenue out of affluent elderly age brackets… Stricter tax compliance measures will flush assets out of the tax havens of Boomer plutocrats. Rationing of high-end luxury services and goods may be instituted to save resources, if such opulence has not already been driven into the shadows by social stigma…

... Public benefits will also be overhauled. Entering prior Crisis eras, government spending on benefits to the nonindigent was minimal. This time, it is massive—and it flows mostly to the elderly…

Most Boomers won’t have their heart in this fight. Here too they will make large concessions and even rationalize them as participation in a larger cause.”

Howe’s predictions have eerie echoes to what is happening with the super tax debate.

Future courses of action

Government policies don’t just happen in isolation; there are economic, social and cultural circumstances which give rise to them.

My analysis above has tried to give context to why this super tax has come about. However, it also gives potential pointers to the future.

By 2040, I’ll surprised if most of the following hasn’t happened:

- Further taxes on wealthy super accounts

- Negative gearing removed.

- CGT discount reduced.

- Family homes, perhaps above a certain value, included in Age Pension assets testing.

- A higher and broader GST.

I’m not suggesting these things are right or wrong. It’s just that the confluence of factors mentioned - the anger of younger generations, rising budget deficits, the large tax concessions for homes, investment property, and super, as well as the seeming resignation of the wealthy to higher taxes – provide a fertile environment for further taxes, especially on the rich.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.