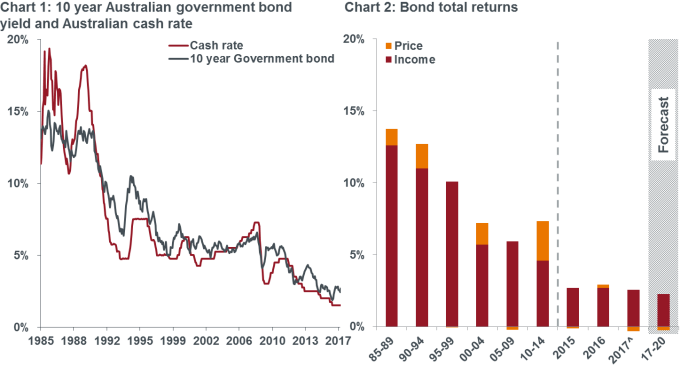

It is hard to believe, but back in August 1982, the Australian cash rate averaged 17% (the unofficial rate went as high as 19%) and the yield on a 10-year Australian government bond was 16.5%. Some 35 years later, the cash rate is 1.5% and the yield on a 10-year government bond is around 2.6%.

Over this period, the Australian fixed interest sector has been in a structural bull market, propelled by the shift from a high to low inflation environment and demographic factors which lowered real rates. More recently, conventional and unconventional monetary easing has driven yields even lower.

For investors in the sector, the last 35 years have generated handsome returns, even allowing for the 1994 bond bear market. Returns of 9.5% p.a. compare favourably to 12% p.a. from the Australian share market and 7.6% p.a. from cash over this period.

Source: Chart 1: Bloomberg, as at 30 July 2017. Chart 2: Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, Ausbond Indices, UBS, SBC Brinson. Spliced history of Australian Bond market returns. As at 30 June 2017. Forecast numbers are estimated projections only. ^CYTD 2017.

Beware the bull complacency trap

A common trap that investors can fall into is becoming complacent about the risks that may be building up in their sector exposures after a prolonged period of structural change and good returns.

With the global economy enjoying a cyclical recovery and central banks signalling a desire to begin withdrawing high levels of policy accommodation, investors’ attention should focus on two sources of risk embedded in the sector benchmark, the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index (benchmark) that have built up progressively since the GFC.

Lengthening benchmark duration = more interest rate risk

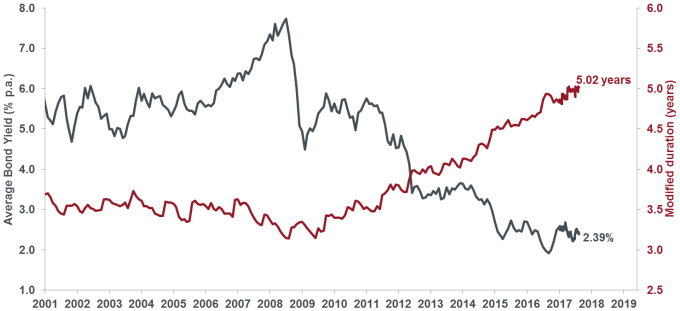

Just because the level of interest rates is low by historical standards does not mean that a small rise in rates will have a limited impact on sector returns. Investors need to be aware that since 2009, the duration (a measure of maturity term) of the Australian fixed interest sector has risen from around three years in mid-2009 to around five years currently.

In 2009 when bond market yields averaged around 5.5% and duration was three years, investors’ exposure to interest rate risk was such that a 1% rise in bond yields would have resulted in capital loss of 3%, delivering a total return of around 2.5% (i.e. the income of 5.5% minus the capital loss of 3% from rising bond yields).

Today, with average bond market yields of around 2.5% and the duration of the benchmark around five years, a 1% rise in bond yields would result in capital loss of 5% delivering a total return of -2.5% (i.e. 2.5% income less 5% capital loss). A 0.5% lift in yields would result in flat returns (i.e. 2.5% income less 2.5% capital loss).

Chart 3: Australian average bond market yield and modified duration

Source: Bloomberg, as at 11 August 2017. Date is monthly to December 2016, daily from January 2017. Australian bond market based on the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index.

With the RBA Governor indicating that the next move in rates is likely to be up, investors need to be mindful of the interest rate risk in the sector benchmark. Over the last few years, investors in passive fixed interest products have enjoyed a good run as interest rates fell and the duration of the benchmark lengthened.

Looking ahead, investors in such strategies need to be aware of their exposure to capital loss from even modest rises in rates. By way of example, the yield to maturity on the benchmark lifted from 1.98% at the end of July 2016 to 2.43% at the end of July 2017. With the duration of the benchmark at historically high levels, resultant capital loss more than offset any income, with returns down 0.24% over the period.

We believe active fixed interest strategies or absolute return strategies, where managers are not bound to hold duration at benchmark levels, are better positioned to preserve investors’ capital in a rising rate environment.

Benchmark compositional risk: lower-returning government debt, less diversification

Since the GFC, there has been significant change to the composition of the Australian fixed interest benchmark. The heavy issuance of increasingly longer-dated government debt (federal, state, supra national) combined with corporate deleveraging has hastened the ‘crowding out’ effect in the benchmark. As a result, the market weight of the higher-yielding credit sector in the benchmark has fallen from 36% in 2008 to around 8% in 2017 currently.

Investors in passive index strategies have progressively lost access to both the higher yields available in the credit sector and diversification benefits of broader holdings in the benchmark. Longer-dated government debt has increased the interest rate risk. The past year highlights the importance of active interest rate management in navigating the gradual reversal of the bond bull market.

Jay Sivapalan is Portfolio Manager, Fixed Interest at Janus Henderson Investors.