Part 1 of Lawrence's interview with Graham Turner can be read here.

Going global the right way

Global expansion has traditionally been difficult for many Australian companies. It was no different for Flight Centre. The difference maker was at Flight Centre, there was a group of co-founders at the helm determined to figure out and evolve their overseas operations. They also had the ability to make quick changes without heavy bureaucracy many other organisations face.

In 1989 the business opened its first overseas shops in London and California. Despite Skroo's (the nickname that Graham goes by) extensive experience in London, the shops struggled to gain traction. Skroo puts it down to two factors: timing and leadership talent. The expansion overseas was premature because in those days Flight Centre did not yet have the level of buying power it needed to acquire the cheapest possible airfares, meaning it could not offer the competitive pricing it needed to break into a new market. Its leadership talent was also quite thin which meant decision-making was made from afar in Australia; on the ground experience was lacking. The disappointing results led to the eventual closing of the London and Californian shops in 1991.

But unlike large corporates, Skroo’s operation was agile, could make quick decisions, and was determined to make the global expansion work. In 1995 they revisited the plan with a much stronger foundation. By then Flight Centre had just floated and had built up 350 shops in Australia, generating about $1 billion in revenues. With that also came a deeper talent pool of managers with greater skill and affinity to what Flight Centre was about - its corporate culture. The previous constraints which prevented a successful expansion were fixed. As Skroo puts it “this time we didn’t underestimate how difficult it was to start something up like that.”

Instead of hiring leaders overseas, Flight Centre sent, as Skroo put it “really good expats”, from Australia with a horizon of five to ten years to lead and grow the overseas operations. This tweak worked. It highlighted the importance of corporate culture and business acumen, which took years to develop. Eventually the expat would hand over to a local manager. Even today the formula for spotting internal talent has not changed - Skroo looks for those who make the right commercial judgements, reflect the corporate culture and are willing to relocate even with young families - “it is a big commitment and people prepared to make those commitments tells you something”.

It was with this approach that Skroo and his team would successfully expand into the UK and US throughout the 1990’s and would set Flight Centre on the path towards a true multinational business it is today.

Applying evolutionary psychology to corporate culture

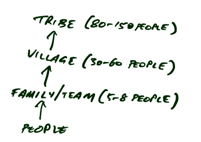

Conventional corporate structure is made of a hierarchical, pyramid structure which Skroo does not ascribe to. The reason is because it slows decision-making, adds bureaucratic layers and disrupts the flow of customer feedback back up to management. The secret formula Flight Centre employed during their rapid pace was based on the theory of evolutionary psychology written by Professor Nigel Nicholson from London School of Economics. The design of an organisation is centred around teams of 5 to 8 people which hark back to how our hunter gatherer ancestors liked to live and work as a family. Typically, 5 to 8 families make a village (an informal group that helps and works with each other), and 3 to 8 villages make a tribe. A tribe ideally consists of 80-150 people. Any larger unnecessary bureaucracy starts to creep in.

On organisational design: “You can take people from the Stone Age, but you can’t take the Stone Age out of people” - Graham Turner

This is how Skroo designed Flight Centre’s frontline teams - roughly 5 to 8 team members in any new shop, belonging to a village of 5 to 8 shops, which in turn linked to a tribe consisting of about 3 to 5 villages (15 to 25 shops). The ideal tribe had around 150 people. As Flight Centre grew beyond those limits, it had to inevitably embrace a level of bureaucracy which Skroo minimised by limiting it to a maximum of 3 or 4 levels - team level, followed by tribe level, then region level, then country level. Senior management should be a maximum of 4 or 5 levels away from frontline staff.

Organisational structure in the context of evolutionary psychology

To this day Flight Centre is structured this way and Skroo remains adamant the size of its board and senior management team should be no different than a family - a maximum of 5 to 8.

How to acquire companies

Skroo has overseen a 20-year track record of acquisitions and proudly stands by the fact he’s made plenty of mistakes. He is the first to admit a success rate of “50/50” is not impressive, but the courage of continuing to take risks is part of why Flight Centre has been successful. It is the reason that has enabled its longstanding leadership team to finetune its acquisition criteria and continue learning from mistakes.

For starters, he eschews “renovators” where on balance more time and capital are required than one estimates. He instead prefers ready-made targets that can already contribute immediately. The premium on acquiring these companies is worth it. Its biggest successes have come from acquisitions in adjacent markets. For example, Flight Centre was able to move into the corporate travel business through a string of acquisitions; it is now one of its largest business areas.

These days, Flight Centre has significant internal capabilities to grow by itself; it will only look to acquire where there are opportunities in niche markets where it does not already have exposure. That may be in new travel segments (such as leisure) or niche geographies where there are new growth opportunities. And this is the other key lesson Skroo has learnt - acquiring is not about empire building for the sake of organisational size; it is about building an advantage in a new niche.

The makings of a founder

To this day, Skroo remains the CEO and retains a significant shareholding. Reflecting on his own journey, I ask him the ingredients which made him a successful founder and what separated him from others. In typical Skroo fashion, he responds analytically with a sense of realism: “getting my hands dirty on an apple orchard by the age of six set a foundation for understanding small business. It’s not a requirement for success, but certainly helped me learn the basics”.

As he developed, it became clear he was a builder - two buses were never enough. With a dry grin he points out he was motivated to pursue life outside the family’s apple orchard because “it was so boring” and of course he pays heed to a splash of luck which helped him survive the cash crisis early on. Somehow, I suspect the element of luck is less than Skroo purports.

Lawrence Lam is Managing Director and Founder of Lumenary Investment Management, a firm that specialises in investing in founder-led companies globally.

The material in this article is general information only and does not consider any individual’s investment objectives. All stocks mentioned have been used for illustrative purposes only and do not represent any buy or sell recommendations.