One of the more controversial parts of our tax system – the capital gains tax discount – is currently under review in Canberra as part of a Greens-run Senate inquiry. The discount means that taxpayers who hold an asset for more than one year pay tax on only half of their gains.

Most submissions to the Senate inquiry have focused on the level of the discount. Arguments range from reducing it to zero to keeping it at 50%, though there is a loose consensus that the current settings are overly generous, and that the discount should fall to somewhere around 20–30%.

But rather than just debating the level of the discount, perhaps we should consider the reasons why we have such a discount in the first place and if there is now a better way to deal with these concerns?

Let’s start from first principles. Why shouldn’t capital gains just be taxed like other forms of income?

There are two good reasons why a realised capital gain shouldn’t be treated in line with other forms of income.

First, part of any capital gain is inflation. If you purchased some shares and they went up in price, but at the same time the price of the goods and services you would have purchased increased by the same amount, then this gain would not be “income” as you can’t buy anything extra with it.

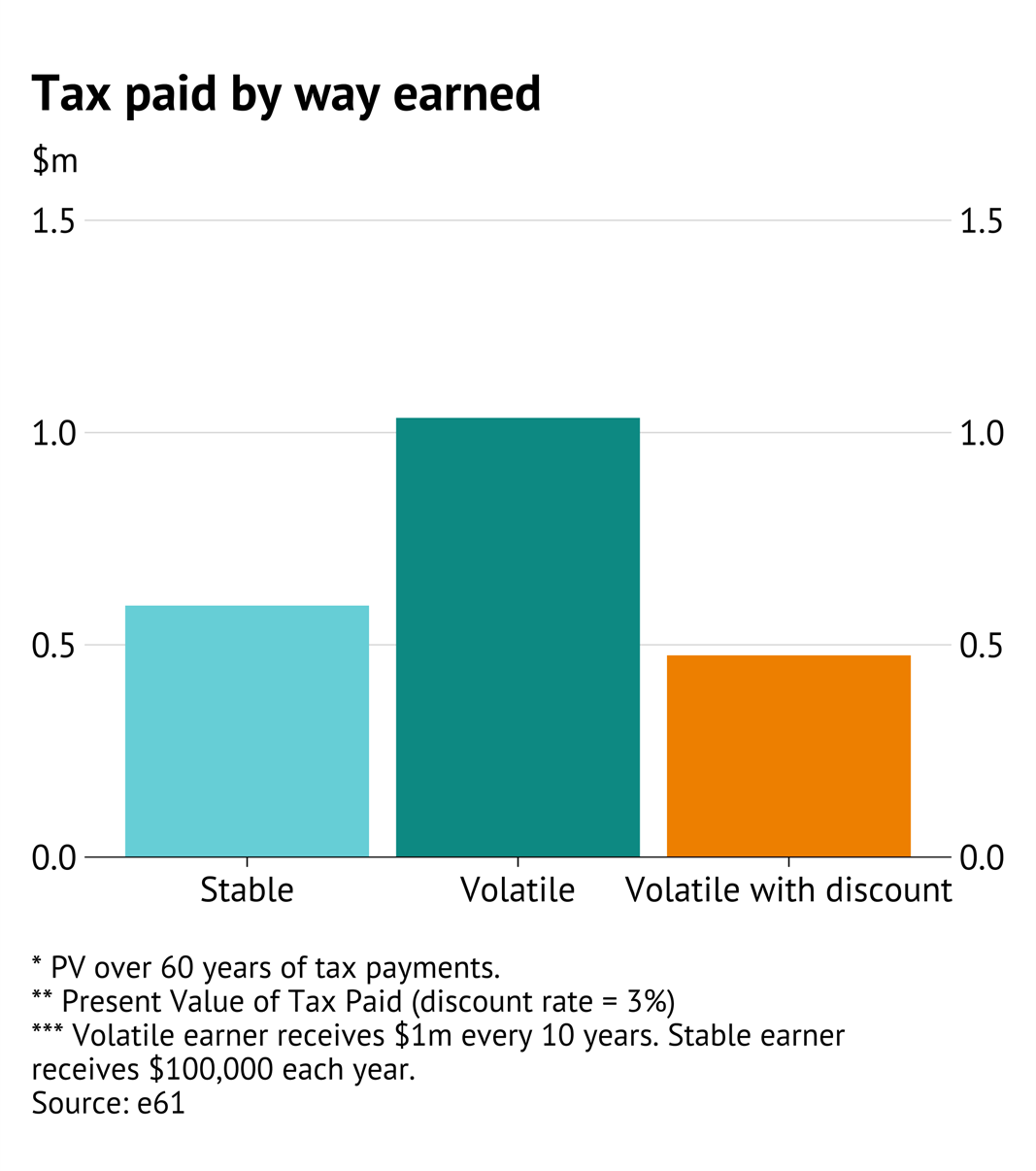

Second, capital gains are lumpy: they don't arrive in regular instalments like wages. Shares are typically held for four years before sale, houses for ten. And because our tax system is progressive, cramming several years' worth of gains into a single year pushes many taxpayers into a higher tax bracket.

To take a stylised example, an entrepreneur with lumpy income – earning the average full-time income as a capital gain once every 10 years – would pay 75% more tax than a wage earner receiving the same total lifetime income steadily over time.

The current capital gains discount was introduced as a simple way to mitigate these two justifiable concerns. However, it also has two important design flaws.

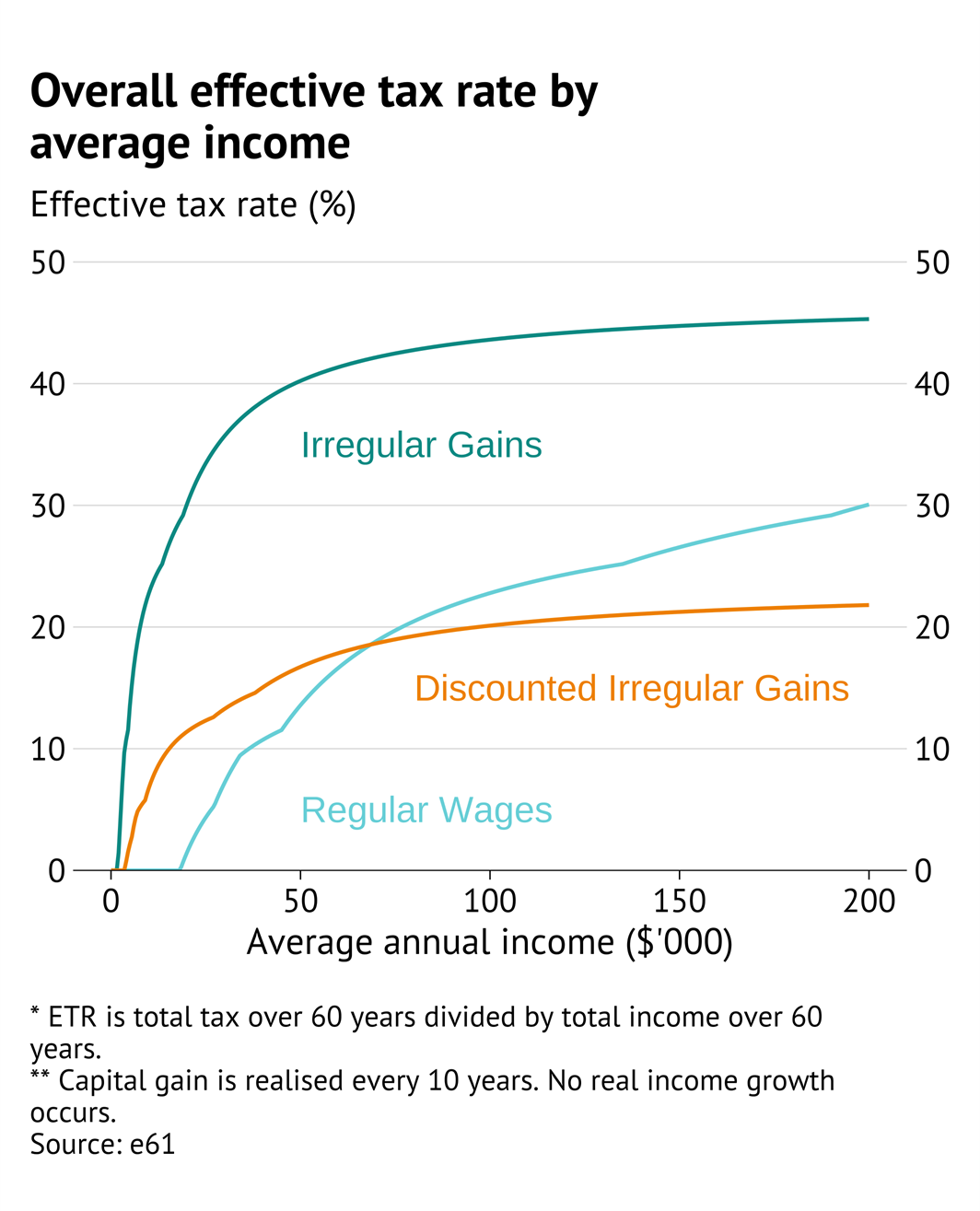

The first flaw is that it overcompensates high-income earners and undercompensates low-income earners for these issues.

Our analysis of tax records suggests that the current 50% discount overtaxes gains for individuals with incomes below $50,000, relative to a comparable wage earner. The discount then becomes increasingly concessional for higher-income individuals.

The second design flaw is that the capital gains tax discount provides an incentive for investors to shift towards capital gains generating assets and increase leverage.

While part of any capital gain is inflation and thus not real income, this is also true for other forms of capital income. Interest earnings, for instance, also contain an inflationary component, which means they are often taxed too heavily.

Applying an allowance for inflation only to capital gains distorts investment towards assets that generate gains as an inflation hedge. Furthermore, not taxing inflationary gains while allowing expensing for the inflationary component of debt incentivises individuals to leverage up.

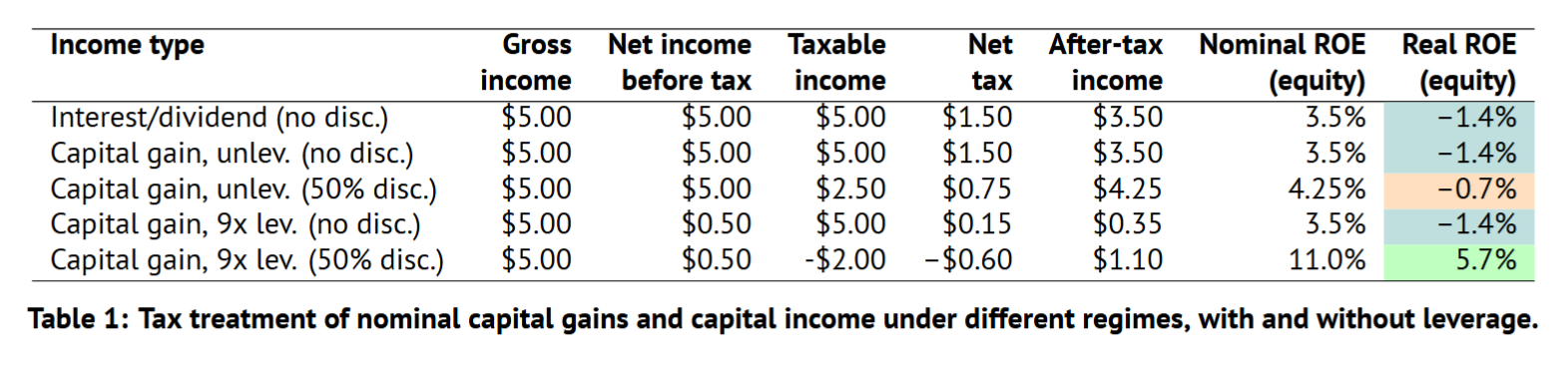

These effects can be illustrated by looking at an asset which only increases in value with inflation. Pre-tax the real rate of return is 0%, which means that a tax system that leads to a negative post-tax return is one that penalises such investments while a tax system that generates a positive return encourages them.

If we assume inflation and interest is 5% per annum and there is a flat 30% tax rate, then taxing nominal gains without a discount would lead to a –1.4% return on equity.

The capital gains discount would halve this loss to –0.7% if the asset was purchased without debt, seemingly reducing the distortion associated with taxing inflation. However, it also biases investments towards capital gains generating assets as the return on other capital income with the same real rate of return (e.g. interest) would remain –1.4%.

Leverage changes the story significantly when capital gains are discounted. If the individual borrows 90% of the capital necessary for the purchase, and has other taxable income, the return on equity becomes 5.7%. The investor generates a positive post-tax rate of return even though the asset price only increased by inflation!

This benefit for leverage would not happen without a capital gains discount – as income and expenses would be treated consistently by the tax system. In this case, the return would be –1.4% irrespective of the amount borrowed.

For this reason, individuals will borrow too much to purchase assets which act as an inflation hedge if there is a capital gains tax discount.

So, what's the alternative?

Prior to 1999, Australia’s tax system offered income averaging for lumpy gains and reduced taxable capital gains by inflation.

As discussed in the e61 submission to the Senate inquiry, this prior system highlights a way forward. With modern administrative data collection, such income averaging and inflation allowances could be incorporated into the taxation of all capital income in Australia – with appropriate adjustments to allowable expenses.

Rather than picking an arbitrary discount rate, these mechanisms would directly target the issues with taxing capital income at full rates. Simplified approaches – such as the dual income tax recommended by the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute – would also address many of these concerns.

In 1999, there was an argument that the trade-off between precision and compliance costs justified a broad 50% capital gains tax discount – leading to reasonable debate about whether this number is still appropriate. In 2025, it's worth stepping back and asking whether we can do better than just picking a new number between 0 and 50.

Matthew Maltman is a Senior Research Economist and Matt Nolan is a Senior Research Manager at the e61 Institute.