Shortly before Christmas, Treasury released draft legislation for a new version of the controversial Division 296 tax – the additional tax for those with more than $3 million in super. The new version does represent a significant improvement on the original proposal in that it no longer includes taxing unrealised capital gains. But there are definitely some stings in the tail.

Key points

If implemented exactly as outlined in the draft legislation, the new tax:

- is due to start from 1 July 2026 (ie, the first financial year would be 2026/27) rather than 1 July 2025,

- would be a brand-new tax levied on individuals (although it can be paid from super) – in addition to all normal super taxes which will remain exactly the same,

- will be charged as an extra 15% tax on the proportion of super ‘earnings’ (more on this later) that relates to an individual’s super balance over $3 million. However (the first sting in the tail), there would be a further extra tax of 10% on the proportion of super earnings relating to the proportion over $10 million. This means some people will pay an extra 25% (15% + 10%) tax on some of their super earnings. The Government talks about ‘headline rates’ of tax on those with large super balances being up to 30% and 40% respectively – this is simply adding the normal super fund tax rate of up to 15% to the new tax rates above,

- unlike the old proposal (which involved taxing unrealised capital gains), uses normal tax principles to calculate ‘earnings’ for Division 296 tax purposes. It even incorporates some special protections to allow SMSFs with capital gains built up before 30 June 2026 to avoid paying Division 296 tax on these gains when the assets are eventually sold, and

- calculation will have some similarities to the previous draft bill in that it will be:

A percentage x earnings x a tax rate

but (a second sting in the tail), the percentage will be worked out differently and the new method is designed specifically to stop people avoiding the tax by taking a lot of money out of super during the year.

A simple example

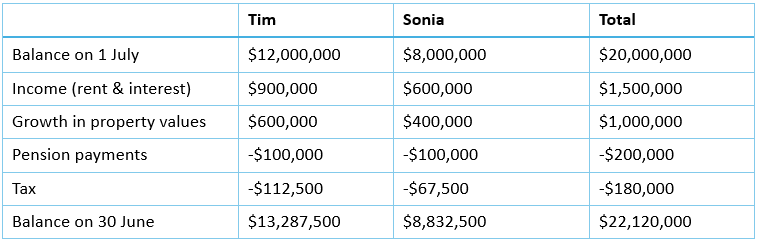

Tim and Sonia have an SMSF worth $20 million at the start of the year (1 July). Tim has $12 million and Sonia has $8 million. During the financial year, their super fund received income (rent on various properties and interest) of $1.5 million, and the properties grew in value by $1 million (but no properties were sold – no capital gains were realised during that financial year). Let’s say they drew pensions of $100,000 each ($200,000 in total). Their super fund would pay income tax in the usual way – let’s say that was around $180,000. For now, we’ll just ignore any expenses the fund might have paid to keep the calculations simple.

During the year, their super fund would have grown by $2.12 million (ie, $1.5 million in rent and interest plus $1 million in growth less pension payments and taxes of $380,000 combined).

Let’s say Tim and Sonia’s balances are $13,287,500 and $8,832,500 respectively at the end of the year as shown below:

We then work out their Division 296 tax in 4 steps:

Step 1: Add up the whole super fund’s ‘Div 296 earnings’.

This is $1.5 million (rent and interest). Notice how the “growth” amount is completely ignored? (Under the old version of Division 296 tax, it would have been included in each member’s earnings and the total amount would have been reduced by their share of the fund’s tax bill of $180,000).

Step 2: Divide the fund’s ‘Div 296 earnings’ between the two of them.

The details of how this will be done are yet to come – we need to see some more regulations. But based on what we do know, it’s likely the split would be 60% to Tim (on the basis that he has around 60% of the fund) and 40% to Sonia. This means the $1.5 million divided between them would be $0.9 million and $0.6 million respectively.

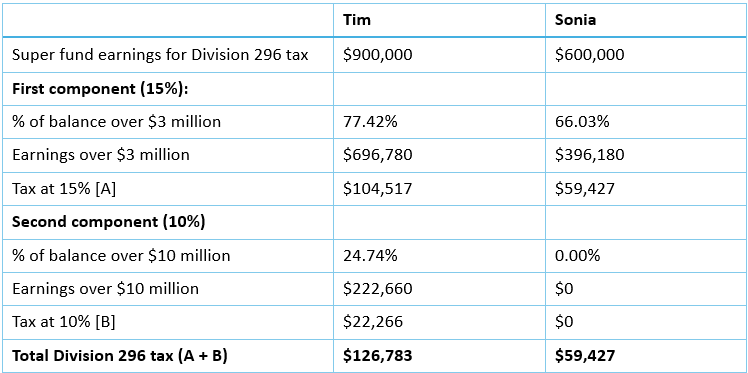

Step 3: Work out the % of their super balances over $3 million and $10 million.

Under the old version of Division 296 tax, this would have been worked out using their end of year balances only. The new version will be based on the higher of their balances at the start and end of the year (with a special concession in the first year – 2026/27 – more on this below).

In other words, for Tim we’d work out this % based on the higher of $12,000,000 and $13,287,500. Like many people, Tim’s super balance has grown during the year so the right number for him will be $13,287,500.

Of this, 77.42% is over $3 million (ie, his balance is over $3 million by $10,287,500 and this represents 77.42% of his total balance). In addition, 24.74% of his balance is over $10 million. The equivalent figures for Sonia are shown below.

Step 4: Apply the two tax rates to these proportions of the earnings amount.

There are some interesting features of this tax that will change some of the planning strategies we might have adopted under the old method.

A different approach for the percentage

As mentioned above, when working out the proportion of super over a threshold ($3 million or $10 million), the new draft bases this on the higher of the member’s super balance at the start and end of the year. Previously it only depended on the balance at the end of the year.

This is a big issue for those hoping to realise gains in a particular year and then withdraw a lot of their super before the end of the year to avoid Division 296 tax. The Government was presumably on to this one!

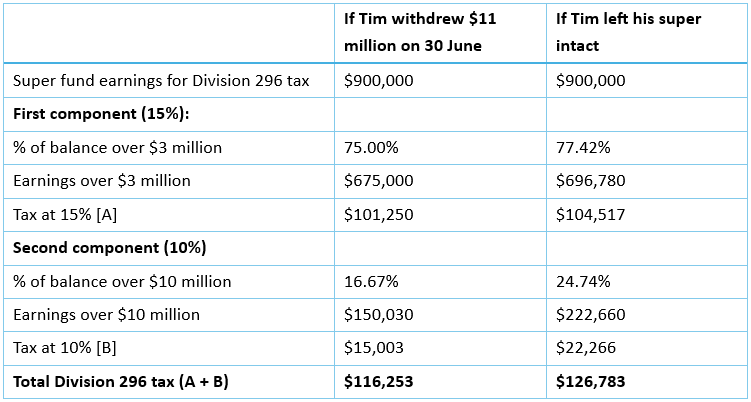

For example, what if Tim had withdrawn $11 million of his super right at the end of the year (bringing his balance down to $2,287,500)? Under the original proposal, this would have been enough to avoid Division 296 tax altogether. His super ‘earnings’ might still be very high but the percentage subject to the tax would have been 0%.

Under the new method, the super balance used to work out how much of Tim’s super fund earnings is over $3 million and $10 million would be based on the higher of two balances: his balance at the start of the year ($12 million) and end of the year ($2,287,500).

The big withdrawal would change his Division 296 tax a little bit but not much:

There is a special transitional rule in 2026-27 – the percentage will be based on the member’s super balance on 30 June 2027 only.

That means people seriously intending to extract a lot of superannuation because they have no intention of ever paying this tax realistically have until 30 June 2027 to do so. If Tim’s big withdrawal (above) had occurred in 2026/27, for example, he would have been able to avoid Division 296 tax entirely.

Capital gains

So far we’ve ignored the possibility that Tim and Sonia’s SMSF might sell one of its properties during the year.

If it did so, the fund would realise some capital gains. Normally these would be taxed and now that we’re going back to ‘normal tax principles’ for Division 296 tax, they’ll be caught in the tax net too.

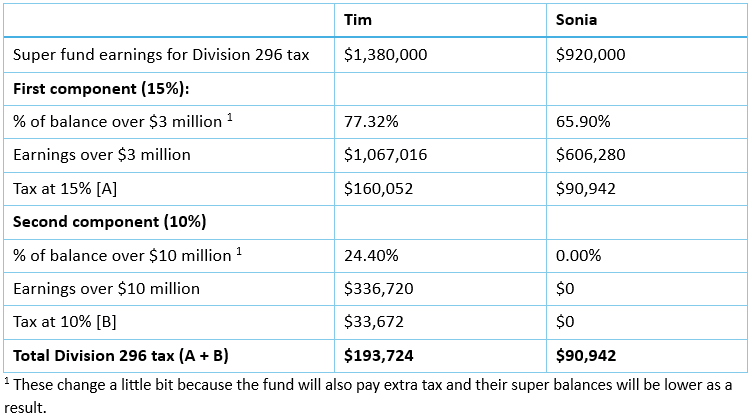

For example, let’s imagine everything is exactly as before but this time, Tim and Sonia’s SMSF sold a property. The property was purchased for $1.8 million in 2027 and sold for $3 million in 2030, making a capital gain of $1.2 million. This would trigger an extra tax bill in the super fund (so their end of year balances would be a little lower) but it would also mean the ‘earnings’ used to work out their Division 296 tax would include some of this capital gain.

Super funds only pay tax on two-thirds of their capital gains if they’ve owned the asset for more than 12 months but even so, the ‘earnings’ for Division 296 tax would increase from $1.5 million to $2.3 million ($1.5 million plus $0.8 million i.e. two-thirds of $1.2 million).

This changes the figures a lot:

Note – if Tim and Sonia’s SMSF had capital losses carried forward from previous asset sales, these can be used to reduce the normal tax paid by the fund. The same applies to Division 296 tax. For example, the ‘earnings’ amount shown above was $2.3 million between them because it included $0.8 million (two-thirds of the $1.2 million capital gain). If the super fund had $0.3 million in losses carried forward from previous asset sales, only $0.6 million would be included in earnings (two-thirds of $0.9 million).

There is a special concession that allows Tim and Sonia to shield existing growth from this tax.

Importantly, if Tim and Sonia’s SMSF already owns the property on 30 June 2026, any growth built up before that date can be protected.

For example, if they bought it in 2020 rather than 2027 and on 30 June 2026 it was already worth $2.5 million there would be an extra step.

While the fund would still pay the normal amounts of capital gains tax (i.e., based on the whole capital gain of $1.2 million), the earnings used for Division 296 tax would be less. The capital gain taken into account for Division 296 tax would only be $333,333 (ie, two-thirds of the gain that built up after 30 June 2026, being $500,000).

A critical point here – that special treatment isn’t automatic. Funds wanting to take advantage of it will need to opt in using an ‘approved form’.

The requirement to opt in is an important one because it comes with a deadline: the due date of the SMSF’s 2026/27 annual return. Funds that – for example – lodge their return late will miss out. Similarly, funds that just lodge their return without specifically opting in will miss out (we don’t know exactly what the opt in process will look like yet).

Note that any SMSF can opt in – even one with no members who have more than $3 million in super at 30 June 2026. It might still be attractive to do so if any of the members expect to be over $3 million in the future and the fund has already accrued large gains.

The ‘opt in’ happens at a fund level rather than a member or asset level. In other words, funds are either ‘in or out’ of the relief, they don’t get to choose to opt in for some assets but not others (eg assets that are currently in a loss position). It also – curiously – means members who join that same fund in the future will benefit from the opt in if pre-July 2026 assets are eventually sold while they are a member.

A new challenge for the future

The special protection for capital gains built up before 30 June 2026 will be useful in the near term but eventually most SMSFs will be selling assets they bought after this tax started.

The way in which the percentage is calculated (taking into account both the start and end of year super balances) creates all sorts of headaches in different circumstances.

Example: Jane and Kris both had $15 million in super at the start of the year (1 July 2030). They were fortunate in that one of their SMSF’s investments exploded in value during 2030/31, significantly increasing their super (it’s May 2031 and looking more like $25 million each). They would like to de-risk and sell the asset but they can see Division 296 tax will be a major issue for them. They need to make some decisions quickly.

They could hang on to the investment for now and accept that when they eventually sell it in a few years, their ‘Div 296 earnings’ will include a very large capital gain AND the percentage of this amount which is subject to tax will be based on a really high balance (likely to be $25 million at least). Even if they make a large withdrawal from super in the same year they sell the asset, this might not lower their tax percentage very much since we’ll now look back at their start of year balance as well.

Or they could sell it ‘now’ (May 2031) and immediately withdraw the money from super. That way at least the Division 296 tax percentages would be based on $15 million (ie, their super before it increased dramatically).

Or they could hope that in the future they will have other assets they can sell first (at much lower gains) to get their overall super lower at a time when their ‘earnings’ are still low. This will require careful management!

Different CGT relief for large funds

Large funds will adjust the fund’s actual realised capital gains for the first four years only (2026/27 – 2029/30) – presumably on the basis that mostly assets are turned over during this timeframe (whereas many SMSFs tend to be ‘buy and hold’ investors). We’ll need the regulations to see exactly how this will work.

Splitting the fund’s Division 296 earnings between members

Once the fund has calculated its ‘earnings’ overall, it will need to split that global amount between members since Division 296 tax is a personal tax calculated at the individual level.

For an SMSF, the precise method will be set out in Regulations (yet to be released) but additional guidance issued by Treasury indicates the regulations will involve relying on a special actuarial certificate. This makes sense in that the style of calculation required is similar to the calculations used for actuarial certificates already in place for many pension funds.

Of course, not all SMSFs with members impacted by Division 296 tax are in pension phase – so some accumulation funds will find they need an actuarial certificate for this purpose for the first time. Hopefully this will be administered in a practical way so that it is not necessary for every single fund to obtain an actuarial certificate ‘just in case’.

Interestingly, Treasury has specifically highlighted that SMSFs holding specific asset pools for specific members will be required to use the same method as all other funds – effectively ignoring any specific asset allocations.

Large funds (ie other than SMSFs, small APRA funds) will again use a different approach. They will be required to allocate the Division 296 earnings amount in a “fair and reasonable” way between members.

What if ‘earnings’ are negative?

Unfortunately, there’s no refund for Division 296 tax under these circumstances – there’s just none payable for the current year.

This might happen if, for example, the fund has expenses that are much higher than its assessable income. While these could be carried forward and used to reduce both fund taxes and Division 296 tax in the future, there’s no immediate refund to the member.

What’s next?

The consultation period for this Bill is short – it ends on 16 January 2026. The Government is obviously keen to get the legislation tabled and passed quickly. They have included some improvements to the Low-Income Superannuation Tax Offset (LISTO) in the same Bill – presumably in the hope this will encourage other parties to support it.

It’s difficult to see where significant changes might be made – so I think we can expect to see this introduced as law if the Government can navigate the politics.

Meg Heffron is the Managing Director of Heffron SMSF Solutions, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This is general information only and it does not constitute any recommendation or advice. It does not consider any personal circumstances and is based on an understanding of relevant rules and legislation at the time of writing.

For more articles and papers from Heffron, please click here.