The 2017/2018 financial year was a bumper time for many fund managers, but something else jumped out at us when reviewing performance figures. When the worst equity manager returns 5%, you know it has been a near-perfect year. It’s the same in all classes with balanced super funds doing 10%+ and small cap funds returning between 10% and 35%.

But what really stands out is the best-performing Australian equity managers (Bennelong, Platypus and Colonial First State) achieved between 23% and 26%. In our experience, widespread 20% returns usually signal the ‘start of the end or the end of the start’. It’s not quite 2006 and 2007 when the median super fund returned 14% p.a. or 1987 when some equity funds hit 50% returns, but we’re reaching the stage where markets are in that swampy area between complacency and hubris. When things go pear shaped, everyone will say that it was oh so obvious.

Great year(s) fellas!

Manias affect all investors to some extent, so it’s unfair to point out individual examples, but the 2007 - 2010 period produced some wonderful examples of what happens at the end of complacency. MTAA was a large industry superannuation fund which had made a more extreme asset allocation than its peers. It was heavily weighted to alternative assets such as private equity and infrastructure. The fund was only 4% invested in traditional defensive assets. Everything else was either ‘growth’ or ‘alternative’ with 45% of the portfolio in illiquid assets (alternatives, PE, property etc.) with a large derivative overlay. It was working well too. By 2007, the fund had returned 17% p.a. for the previous four years. Maybe the investment team thought illiquid and alternative assets were safe, or maybe they thought it would never end. We remember contacting them (or their advisers) and were told politely that they only invested in assets that generated returns greater than 10%.

It didn’t work out for long though. The Fund generated a -23% return in FY2009 (and it was worse intra-year) and it took five years to generate returns higher than the low single digits, by which time equity markets had generated 20%+ gains. The investment return for the decade to 30 June 2017 was a meagre 2.4% p.a.

When good assets go bad

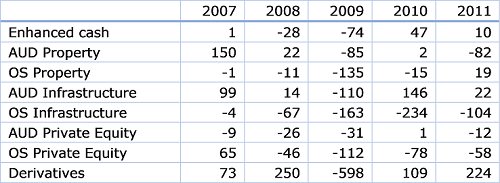

You would have expected the ‘true’ growth assets like equities to get shredded by the GFC, but they recovered quite quickly. What really killed MTAA was the exposure to alternative assets which were, or still are, considered ‘safe’ investments. The table below shows the capital gains and losses (in $ million) attributable to the alternative asset classes for each year.

Alternative and illiquid assets

Source: MTAA Annual Reports.

There were a couple of pertinent points:

- The divergence between the domestic and international versions of the same asset classes is enormous. Australian infrastructure bounced quickly (which is what you would expect as interest rates fell), but international infrastructure was still generating losses almost five years later. Similarly with property. While the Australian version was fine, international property was double digit negative.

- Given the point above, it’s interesting to speculate on why Australian ‘alternative’ assets in the post-GFC period did so well. Maybe they are genuinely low risk, maybe they were saved by the lack of a real recession or continued cash inflows into the sectors meant that prices never fell. We’ll find out the real reason some time in the next decade when markets falter.

The biggest saviour

The only reason MTAA did not end up a total rout was that the fund maintained its cash inflows. This was a combination of the super guarantee cashflows which are virtually impossible to turn off, and super fund reporting, which is well after the event. For most super fund members, the reporting comprises a colourful brochure once a year and which most recipients either don’t understand or throw in the bin. Few people withdrew their money from MTAA, which meant that the capital losses in 2008, 2009 and 2010 were spread out on a wider denominator and the 22% loss was much smaller than it otherwise might have been if their liabilities were more liquid.

Investment drivers

Investments are driven by factors which will determine their ultimate return outcomes and how messy the path is. For example, investment-grade bond returns are driven by duration and how likely an investment-grade company will default (not very often). The path is also influenced by sentiment. So, the ultimate returns of investment-grade bonds are stable and the path variability is driven by the duration.

Alternatively, equity and infrastructure value is driven by the economy and management and wars and politics and demographics, etc. Sentiment and risk aversion drives the path, and because they are very long duration, both the ultimate value and messiness of the path are highly variable and unknown. The example in the MTAA case is the offshore infrastructure which lost money for at least five years.

The implications for hybrids

We believe hybrids are closer to investment grade bonds with respect to ultimate returns, but they have other factors of not only default risk but near-death experiences with the issuer that will affect return outcomes. Their path is also affected by sentiment, but because of their shorter duration, they are far less volatile than equities. Which is why in the past 20 years, hybrids have had bad years, but they have tended to only last one year.

The other read is that investors should demand big premiums for illiquid investments, but they don’t receive premiums except in the immediate aftermath of a crisis. They then get hit by the next crisis and either scratch their heads or complain. It’s a non-trivial outcome as can be seen by the MTAA post-decade return of 2.5% p.a. driven by their exposure to illiquid assets at the wrong time of the cycle. Hybrids were more liquid than Australian corporate bonds in the last liquidity crisis and arguably more liquid than high yield bonds are now.

Campbell Dawson is Executive Director at Elstree Investment Management Limited. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual investor.