Death and taxes are the proverbial certainties in life. Life, however, is full of uncertainties, like just how long a recently retired 65-year old will actually live and what the share market is going to do for the first ten years of their retirement.

Using a concept first explored by Moshe Milevsky, it is possible to compare the relative uncertainty around retiree lifespans and equity market returns using Australian data.

Market uncertainty

Investors are, of course, aware that equity markets are volatile. If a capital sum is invested for a period of time, the amount of capital available at the end of the period will be uncertain. The question is: how uncertain?

This question depends on the investment timeframe. As a rule of thumb, equity markets are volatile in the short term, but over the long run there is some reversion to the mean that partially reduces this volatility. For a retiree, the impact of returns in the first 5–10 years after retirement has a big impact on their capital base. So a 10-year period is an appropriate term to consider in a retirement context.

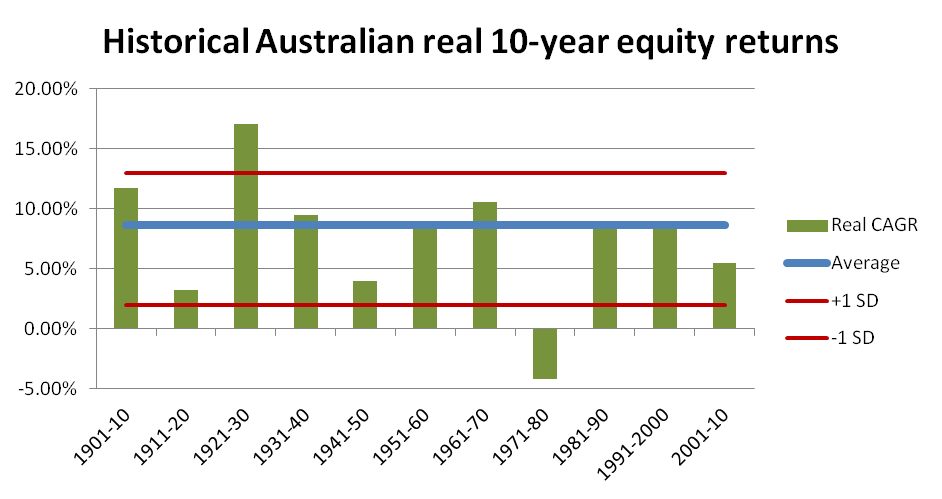

Data on equity markets from Credit Suisse, based on work by Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, provide the real returns on equities in Australia since 1900, split into 10-year periods. The returns for each decade can be seen in figure 1. These returns include all dividends and are before tax.

Figure 1. Real returns on Australian equities in 10-year periods.

Source: Credit Suisse using data from Dimson, Marsh and Staunton

One way to consider volatility is to look at the variation (standard deviation) from the average outcome (mean). Using Australian equity market returns, the mean real growth can be measured by the 10-year effective compound annual growth rate (CAGR): 8.7%. The volatility in this example is the measure of plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean, which is 13% and 1.9%, respectively.

Another way to look at volatility is to use a co-efficient of variation (the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean). Using the same average 10-year Australian example, the co-efficient of variation is 47%.

Life expectancy vs actual lifespans

What about the variation of actual retiree lifespans from average life expectancies? How much certainty can a retiree have about the length of their own life from retirement onwards? The answer to this question might be a surprise for most retirees and their advisers.

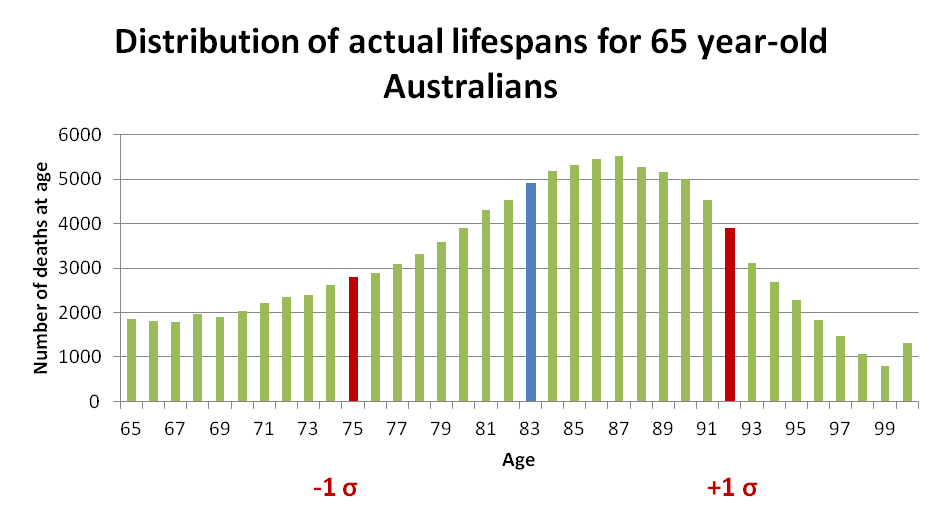

In 2012, the most common age at death for someone who was 65 years-of-age or over was 87 (the mode). Despite this, taking the probability of survival from age 65, the mean ‘expected’ length of life for a 65-year-old was 18.1 years or to age 83. In reality though, very few people live exactly that long. Some live longer and some not as long. The range of actual lifespans around this mean point is represented by a standard deviation of 8.4 years either side of 83, figure 2.

Figure 2. Number of deaths (males and females) by age at death, Australia 2012.

Source: ABS

For a 65-year-old, it is also possible to measure the volatility as a ratio between the variation of actual lifespans to the average life expectancy. Remarkably, the co-efficient of variation, the range of actual lifespans proportional to the mean, is also 47%. So it turns out that a 65-year-old has to cope with a lot of uncertainty around how long they are actually going to live.

Relative uncertainty

Both equity market returns over 10 years and actual lifespans (versus average life expectancies) for 65-year olds have the same relative level of uncertainty: 47%. While this result is generated through some selective data use, it does highlight that both the equity markets and actual lifespans at retirement are similarly uncertain.

Summary

Longevity risk is not just the risk of living longer and outliving retirement savings. Uncertainty around a retiree’s actual lifespan is another, more complex, aspect of longevity risk. Financial models and retirement plans generally revolve around average or expected life expectancies, done so for the sake of convenience. This is a serious industry shortcoming.

Two known retirement uncertainties – a retiree’s actual lifespan and the money earned on equity investments (pre-tax investment returns) – have a surprisingly similar dimension. Both forms of uncertainty need to be managed in retirement at the same time. The first step in doing this is to move away from planning for averages. Retirees know that they won’t achieve average share market returns and will build a portfolio to adjust for this.

What far fewer retirees will have realised is that they will almost certainly not live to their average life expectancy either.

Jeremy Cooper is Chairman, Retirement Income at Challenger Limited.