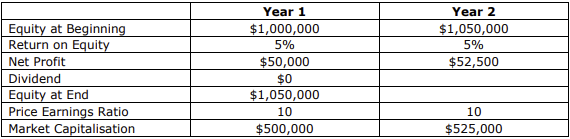

In last week’s Cuffelinks, I showed this table, where a company with a profit of $50,000 was trading on a price to earnings ratio of 10, to give a market capitalisation of $500,000. It did not pay a dividend, and in the second year, it made a return on equity of 5% again, giving it $52,500 in net profit. I left you with the question, with profits and market capitalisation rising, what’s the problem?

Table 1: How to lose money despite profits and capitalisation rising

On the surface things look rosy. The company is growing, equity and profits have increased and management is no doubt drafting an annual report that reflects satisfaction with this turn of events. But not all is as it first appears. Indeed management has, perhaps unwittingly, dudded shareholders.

Dividends and capital gains

As a shareholder your return is made up of two components – dividends and capital gains. If two dollars is earned and you don’t receive one of those dollars as a dividend, then you should receive it as a capital gain. If, over time you don’t, it has been lost and management may be to blame. Every dollar that a company retains by not paying a dividend should be turned into at least a dollar of long-term market value through capital gains.

The company has not achieved this and unfortunately lost its investors money. Even though the company appears to have grown – remember equity and profits are indeed growing – the reality is that as a shareholder you have lost money. How? The company ‘retained’ all of the $50,000 of the profits it earned in Year 1. You received no dividends. All you got was capital gain but the capital gains were only $25,000. In other words the company failed to turn each dollar of retained profits into a dollar of market value. And so investors have lost $25,000. If the situation were to continue, you should insist that the company stop growing and return all profits as dividends and if that is not possible, the company should be wound up or sold.

What happened to the other $25,000? You didn’t get the money as a dividend and you didn’t get it as a capital gain. It was lost. The only way of receiving it is if the price earnings ratio went up. That would require people to pay more for the shares and hoping for that to happen would be like betting on number 5 in race 7 or betting on black. And that is speculating not investing. It might happen but there is no way of predicting it. The worst business to own is one that consistently employs growing amounts of capital at very low rates of return. This is because for a low-return business demanding incremental funds, growth harms the investor financially.

By retaining money, the company is hurting investors as it expands. The reason for retention of profits is largely irrelevant because, either the money needs to be retained which makes it a poor business or management chooses to retain which makes them poor decision makers.

Many investors don’t understand this very real way of losing money even when the company is reporting profits. But investors aren’t the only ones for whom this lesson is lost. A large number of company directors don’t understand this ‘loss’ either or, if they do, they apply their knowledge with a dose of schizophrenia. Inside their businesses, they employ managers in a variety of divisions, who in turn conduct analysis to determine whether to expand their domain. If the returns aren’t high enough they don’t invest in expansion, instead sending the profits back to head office to be invested elsewhere for higher returns. But when the whole business isn’t earning a high return on equity, those same directors often don’t send the money back to the owners to be invested elsewhere. They keep the money! They find something to buy or they pay themselves more. And some, even if they do pay the profits out as a dividend, replace what they paid out by raising money through a dividend reinvestment plan or some other form of capital-raising. This is not a problem for a high return business, but it is reprehensible for a low return business with few prospects of improving its earning power (return on equity).

Back to our company above, many chief executives will present its results in the annual report as reflective of a great year. What they won’t say is that they have lost half of your money!

Thanks to return on equity, we are able to assess management’s treatment of shareholders and discern whether they are favoured or flouted.

Management act like owners

It is important to look for businesses where management act like owners and treat shareholders like owners. Keeping funds for growth when the returns are low is not acting like an owner. A manager who behaves this way is not treating you like one either. As Adam Smith observed in 1774, it is almost impossible to align the interests of a manager with those of the owner when the manager is merely employed to manage the company on the owner’s behalf.

The decision by management to pay dividends or retain profits falls under the heading of ‘capital allocation’ and when managers are making capital allocation decisions, it's essential that they increase the intrinsic value of the company on a per-share basis and avoid doing things that destroy it. In Part 3 of this guide, I will show how allocation decisions can have a material impact on the per share intrinsic value of a company. For executive directors, while it is important they understand how to run the business to its full potential, this knowledge and the positive results are wasted if the board knows little about capital allocation.

The above example demonstrates that a company with a low rate of return on equity will lose money for its shareholders if profits are unwisely retained. As Warren Buffett further observed, if profits are unwisely retained it is likely that management have been unwisely retained too.

Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund.