A defining trait of globalisation is how companies stretch their assembly lines around the world so that goods are made across many countries a long way from where they were sold. Western companies created ‘global supply chains’ over the past three decades by innovations such as:

- the shipping container that reduced transport costs and times

- the arrival of instant communications that allowed management to coordinate production

- the welcoming of foreign investment in emerging countries and

- the cheap labour that didn’t need to be highly educated to operate the machinery in the factories that were moved to China or elsewhere.

The shifting of low-paid factory jobs to the emerging world (where they became sought-after well-paid work) has had vast longer-term political consequences because it boosted inequality within countries while it reduced inequality between countries. The changes wrought by globalisation that have the most political currency are the US trade deficit with China and the widening inequality in the US that helped elect Donald Trump. A rise in protectionism and the rebuilding of immigration barriers that could occur over Trump’s time in power are often flagged as the greatest threat to the free flow of goods, people and money around the globe.

Industrial internet is the next big thing

But there is a larger, longer-term development that is likely to lead to a faster unwinding of globalisation. This catalyst is the coming of the industrial internet. Advances driving artificial intelligence and the internet of things (when devices communicate with one another), and their offshoots such as 3D or additive printing, robotics and automation will revitalise manufacturing in the developed world while dimming the appeal of locating factories in the emerging world.

This will occur for two main reasons.

The first is that western industry will rely more on highly-educated workforces to commercialise the latest technology and to build and operate smart factories, and these skilled people can be found at home. The second is the digital world will be a capital-intensive one. Thus, western manufacturers will have less need for the cheap labour found in the emerging world. The economic, investment, social and political consequences that will follow as technological advances unwind globalisation are vast. They will unfold for decades.

To be sure, the economics of making uncomplicated (or low-end) manufactured goods may still justify global production chains sprinkled through the world’s poorer countries. Today’s robots cannot yet do every intricate task traditionally done by hand. Smart factories still employ lower-skilled staff. The workers supervising robots at Amazon’s distribution centres don’t have to be highly-educated. Western countries will still encounter much tech-driven disruption, while the coming home of US manufacturing might feel empty when it doesn’t create enough jobs to compensate for the five million jobs lost in recent decades. Rather than being spurred by technology, it’s higher labour costs in China that is prompting many western companies to relocate factories back home (or to elsewhere in Asia). Other businesses may favour production at home for political reasons.

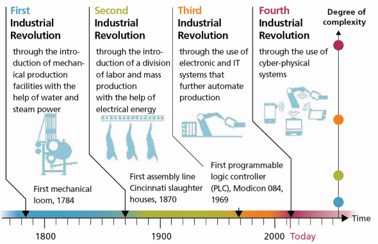

The fourth industrial revolution

However, partisan deliberations, wage relativities and rising protectionism are shorter-term considerations. The technology advancements associated with what many call the fourth industrial revolution are long term. Today’s technological leaps point to western companies locating factories close to their customers. For western companies their most important markets are in the west. The winners when global supply chains crumble will be the developed countries that are home to the most innovative companies, the smartest workforces and the largest consumer markets but also developing countries with big markets and large pools of educated workers at reasonable cost. The losers stand to be the world’s poorest countries that will miss out on attracting foreign investment, the world’s most basic manufacturing hubs, plus, uncomfortably, advanced countries that fail to take advantage of the shift, a list that could include Australia.

Source: DFKI (German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence).

The 3D difference

Technology has always driven the greatest developments in manufacturing. The world’s second great globalisation from 1980, for instance, occurred because technological advances allowed western businesses to exploit the cheap unskilled labour of the emerging world. The world of artificial intelligence and the internet heralds consequences of similar magnitude, but in reverse.

Consider the microeconomic consequences to be provided by 3D printing, which forms part of robotics and rely on the Internet of things. Additive manufacturing (3D printing’s other name) was invented in 1983 by Chuck Hall in the US. When using UV light to place plastic veneer on furniture, he thought of a way to create three-dimensional products.

Fine-tuning software is cheaper and quicker than resetting machinery on factory production lines, especially for one-off or low-volume goods. This attribute reduces the need for multiple specialist factories and overturns the theory underpinning economies of scale, which is built on the finding that the average and marginal costs of making items decline with volume. Reduced economies of scale and the need for fewer factory assembly plants undercut the justification for global supply chains.

An acceleration of 3D-printing speeds has allowed its use in mass production, and further dented the economics driving global production lines. Adidas, for example, is setting up 3D-printing factories in Germany and the US that will allow the footwear maker to deliver fashionable trainers to western shopping centres within weeks of design, whereas it takes months to fulfil orders via Asian-based factories using traditional techniques. Another advantage of mass 3D printing is that it reduces the need for warehouses full of spare parts. Thanks to 3D printing, US construction equipment makers Caterpillar and John Deere are moving their warehouse to the cloud. That brings production home to where head office and tech skills are located. Every advance in additive manufacturing gives western companies more incentives to bring home production.

The way 3D printing undermines the raison d’être of global supply chains is echoed across other forms and uses of artificial intelligence and the internet of things.

The changes are coming

Twenty-four-hour industrial robots lower marginal production costs while displacing the need for cheap human labour to perform tricky tasks. The digitalised world enables robots and devices to communicate across production chains to maximise efficiency, placing a premium on the skilled labour that can build and oversee high-tech plants. Sensors compiling ‘big data’ that is then run through software algorithms boosts efficiency, by forecasting interruptions to production better than factory foremen can. Other sensors will let customers know their items are about to break down, allowing for better client service. The internet of things will propel driverless vehicles, robo-trucks, pilotless planes and automated drones and boost the economics of local, land-based logistics far more than it will smooth international delivery across the seas. Smart grids will lower energy costs in advanced countries, another reason for factories to head homeward and reverse the globalisation of the past three decades.

Michael Collins is an Investment Specialist at Magellan Asset Management. Magellan is a sponsor of Cuffelinks.