Australian superannuation funds face a number of barriers in providing an adequate and sustainable level of retirement income for their members. This article looks at one such barrier, an investor behaviour known as ‘lump sum’ bias.

What is lump sum bias?

Public superannuation funds accumulate capital for people to retire on. But most people find it difficult to calculate how much retirement income their capital can reliably produce from year to year. They tend to over-estimate the amount of annual income it can reliably produce.

Anecdotes about such behaviour are common place. Retirement expert, Don Ezra, suggests that if you ask an intelligent, but non-mathematical, person how much yearly income a lump sum of $100,000 could reliably generate for the rest of their lives, their usual response would be in the range of $10,000 to $20,000. Most experts would put the correct figure at around $5,000 per annum, perhaps even less.

Lump sum bias is where people place a higher value on a lump sum than the actuarially fair and sustainable income stream it could produce.

In rational economic theory, a person should choose the payment outcome that has the highest discounted value. Behaviourally, however, people have a bias towards a lump sum payment. There are a number of factors that explain why people exhibit such bias, including:

- wealth illusion – one simply looks bigger than the other

- affect heuristic – people make a rapid, intuitive judgment because it feels like a good amount

- simple temporal discounting – people generally prefer dollars today over dollars tomorrow

- preference for certainty – people perceive the future as uncertain, and by taking a lump sum payment today, they eliminate a degree of uncertainty, even if they potentially sacrifice some ultimately higher value

- opportunity cost – people believe that having a single large sum might enable them to create or exploit an otherwise unavailable opportunity

- utility of money – people expect the utility of money to decrease as they age and that they will have fewer and less attractive opportunities to enjoy the money.

Evidence of lump sum bias

United States academic Dan Goldstein conducted an experiment where participants were asked to rate their satisfaction with either a $100,000 lump sum or monthly payments of $300, $500 or $900 for life. For a 65-year-old, such a lump sum is roughly equivalent to $500 a month for life.

Respondents had clear preference for the lump sum, even compared to the much more actuarially valuable $900 monthly payments. In fact, Goldstein calculated that the ‘indifference point’ (ie where people would take either) between monthly payments and a $100,000 lump sum was $1,065 a month, nearly twice what it should have been.

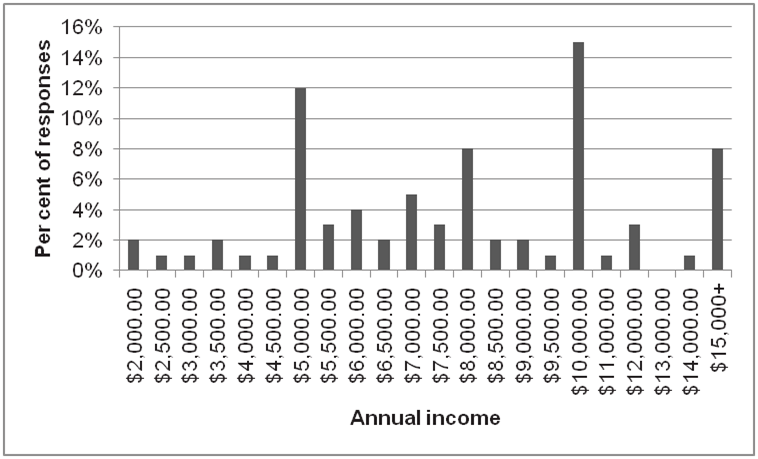

Australian financial research firm Investment Trends conducted a similar survey in Australia. They asked people 40 years of age and over how much minimum guaranteed annual income they would need for the rest of their life, in return for a $100,000 investment. Figure 1 outlines the results. The average response was $8,200 per annum, with $10,000 per annum being the most selected option. This is well above the actuarially fair amount of approximately $5,000 per annum.

Figure 1 Lifetime annual income required for a $100k lump sum

Summary

When it comes to developing an income plan for retirement, lump sum bias can negatively impact the planning process. People who are unable to determine an equivalent income stream from a lump sum might not be saving enough. In particular, people with smaller amounts of retirement savings feel that a lump sum is more adequate for retirement than an equivalent income stream.

Most super fund members get their periodic statement with their latest account balance on it. If they also received a projection of their annual income in retirement in today’s dollars (while highlighting the likelihood of a range of outcomes deviating from the average) it would help prevent them from falling short of retirement adequacy by over-estimating the value of their lump sums.

Aaron Minney is Head of Retirement Income Research and Phil Sainsbury is a Research Analyst at Challenger Limited.