Recently, the UK media was filled with pictures of the Chancellor of the Exchequer (same role as our Treasurer) Rachel Reeves in tears on the floor of the Parliament. Why was she crying? No one was saying, but the tears rolled down her cheeks as PM Keir Starmer was delivering a massive U-turn in his Labour government policy.

PM Starmer shelved a plan to cut disability payments following a rebellion by Labour’s backbenchers. The U-turn raised the prospect of the government hiking taxes or issuing more debt to fund its welfare system. It also cast doubt over the future of Rachel Reeves, who took the job a year ago promising a return to economic stability in Britain by sticking to strict spending rules.

Markets reacted savagely: investors sold off British government bonds and the pound fell sharply. UK government bonds tumbled in price, sending the yield on 10-year gilts up 0.12% to 4.58%. Markets are fearful that the Labour government has abandoned plans to cut ballooning and unsustainable welfare costs.

The UK government’s climbdown points to a broader truth for governments across the developed economies, where weak economic growth means countries are struggling to raise enough revenue to pay for rising costs from an ageing population. With voters largely wary of spending cuts, that leaves higher taxes as the most likely outcome.

Britain is already on course to register the highest tax burden since World War II thanks to big spending during the pandemic and paying out for energy subsidies after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile growth prospects remain soft. The country’s Office for Budget Responsibility says growth could be 1% in 2025 and economists say even this looks optimistic.

The UK’s Labour Party was elected last July with a historically large majority and a mandate to fix the nation’s public finances. Reeves came into office saying her aim was to repair investor trust in Britain’s establishment after former Conservative PM Liz Truss caused a market panic by unveiling unfunded tax cuts in 2022. Truss quickly resigned and her tax cuts reversed. The aftershocks of this policy continued to push up government borrowing costs. But in the ensuing 12 months since its election victory, Labour’s standing in the polls has slumped and it has had to reverse several unpopular benefits cuts to appease left-wing lawmakers who have urged higher taxation instead.

Reeves had said that she will stick by strict fiscal rules, which stipulate that day-to-day spending is matched by tax revenue and that government debt as a percentage of the economy will fall. In March, the cuts to disability payments were hurriedly introduced by the Treasury just before a review of departmental spending was scored by a budget watchdog.

In Britain, the number of people claiming disability or incapacity benefits has risen from 2.8 million in 2019 to 4 million in 2025. Currently around 1 in 10 working age people in Britain are on such benefits. The government aimed to tighten eligibility to bring these numbers down, get more people back into work and save billions of pounds.

But when the government released guidance stating that the cuts to disability payments would push some people into poverty, its backbenchers rebelled.

Will Australia face a similar fate?

PM Albanese’s Labor government was triumphant against a hapless Opposition campaign in the last election, and was not forced to confront serious scrutiny of its fiscal planning. The NDIS is a case in point, similar in many aspects to the UK experience related above.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), launched in 2013, represented a landmark in Australia’s social policy, providing tailored support to individuals with significant and permanent disabilities. However, its escalating costs, structural complexities, and vulnerabilities to fraud raise serious questions about its sustainability and efficacy.

NDIS cost and projected expenditure

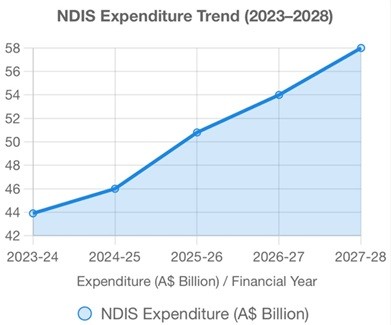

In the 2023–24 financial year, the NDIS cost Australia $43.9 billion, a figure that underscores its position as one of the fastest-growing components of the federal budget. Projections indicate this will rise sharply, with estimates suggesting the scheme could reach $50.8 billion in 2025–26 and potentially $58 billion by 2028, assuming the government meets its target of moderating annual growth to 8%. Over the next decade, cumulative expenditure could approach $600 billion if growth trends persist. The scheme’s cost has already surpassed initial projections, which estimated $22 billion annually by 2018, reflecting higher-than-expected participant numbers and service demands.

The chart below illustrates the NDIS’s cost trajectory from 2023–24 to 2028, highlighting the challenge of balancing growth with sustainability.

Source: Grok

As of December 2024, approximately 646,000 individuals accessed the NDIS, a significant increase from 36,000 in 2016, reflecting an 18-fold growth in participation. This surge, averaging $71,000 per participant annually, has driven costs ever upward.

The NDIS faces structural issues that threaten its long-term viability:

- Cost escalation and sustainability: the NDIS is financially unsustainable, with costs projected to overtake Medicare and defence spending by 2025. The scheme’s demand-driven nature and higher-than-forecast participant numbers have strained budgets, prompting calls for tighter eligibility criteria.

- Inadequate design: the disability community has voiced concerns over insufficient co-design, with changes often implemented without adequate consultation. The 2022 NDIS Act amendments aimed to address this, embedding co-design principles, but critics argue implementation lags.

- Bureaucratic complexity and access barriers: the NDIS’s focus on diagnostics over functional needs creates access challenges, particularly for those with less-defined disabilities. Lengthy delays in plan approvals and reviews further exacerbate participant frustration.

- Retreat of mainstream services: States and territories have reduced funding for non-NDIS disability programs, forcing individuals to rely on the NDIS, which was not designed to cover all disability support needs. This has inflated costs and strained the scheme’s scope. Fraud is a significant challenge, with estimates suggesting up to $2 billion annually, or nearly 5% of the NDIS budget, is misused, including by organized crime syndicates. Unregistered providers have exploited vague guidelines, claiming up to $20,000 per participant for non-essential services like luxury travel, misusing short-term respite funding. Overcharging is rampant, with providers inflating prices for NDIS participants, a practice dubbed the “disability mark-up.”

Look at the case with autism, a difficult condition to diagnose and one open to “interpretation”. Autism is the most common primary disability for NDIS participants, accounting for 35% of all participants. A significant portion of NDIS participants with autism are children, with a majority being male. The NDIS provides funding for a wide range of supports and services for individuals with autism, including therapies, assistive technology, and support workers. There has been a notable increase in the number of boys aged 5-7 accessing the NDIS, with 11.5% of this age group currently receiving funding. In the opinion of critics, this rate of disability cannot be legitimate.

The government has responded with some legislative reforms, but does the government have the courage to implement the major structural reforms required?

The NDIS remains a cornerstone of Australia’s disability support framework, delivering independence and dignity to hundreds of thousands. However, its financial trajectory, structural inefficiencies, and susceptibility to fraud demand urgent reform. The government’s 2024–25 budget allocates $468 million to bolster evidence-based supports, combat fraud, and improve transparency, but success hinges on effective co-design and robust enforcement. As the NDIS navigates its second decade, balancing fiscal discipline with its foundational promise of empowerment will be critical to its survival.

We would rather not see the Treasurer of Australia in tears on the floor of Parliament as promises are broken, the currency tanks and bond rates surge.

Paul Zwi is a Portfolio Strategist at Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.