Hello, and a very Happy New Year to you.

This time last year, I urged investors here at Firstlinks to ignore the “chorus of market watchers insisting the current rally in equities is overdone and that markets are ripe for a correction.” Instead, I explained why 2025 could be another positive year, revisiting the logic behind the bullish stance we’ve maintained since 2022, and through 2023, and 2024.

Turns out, 2025 was indeed another positive year.

For convenience, the logic behind the belief in a solid 2025 was based on two conditions precedent: positive economic growth coinciding with disinflation. Show me a time since the 1970s when disinflation coincided with positive economic growth, and I will show you a period that is likely to have featured a solid stock market performance led by innovative companies with pricing power.

Since 2022, when we turned positive, innovative companies have led investor returns.

From their low in November 2022, Alphabet’s shares have risen 269% at the time of writing, Meta is up 613%, Microsoft is 122% higher, Apple up 115%, Amazon is 177% higher, and Nvidia – the company at the epicentre of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom – is 1,476% above its 2022 low.

So, despite calls at the beginning of 2024, for a downturn, the conditions that buoyed equities in previous years – positive growth and disinflation – persisted. Perhaps unsurprisingly equities markets also rose.

This time last year, however, I noted that disinflation and positive economic growth, when combined with America’s unique advantages – including world’s best productivity and demographics, world-leading investment in research and development and energy self-sufficiency could capture the collective imagination of investors to such a degree that the boom could become a bubble by late 2025.

Then, in August, here in this column, I wrote, “I am not advocating selling out of stocks, not by any stretch, but it may now be a good time to consider bringing forward any planned rebalancing… to redistribute profits to [investments] with less exposure to public markets.”

The thinking is unassuming. What the intelligent individual investor does early on, the crowd tends to mimic later. And even smart people can do dumb things! Even if conditions like disinflation and positive economic growth are in place, prices can (due to the herd’s excitement) stray from even the most optimistic potential scenarios. When this occurs, the reasons that supported an investment at the beginning no longer support it in the end.

Talk of bubbles is now widespread – arguably too widespread to confidently say we are in one. Of course, no market moves in a straight line, and corrections will occur, and can occur, without a catalyst or trigger.

Perhaps, then, we can most productively use our time to decide whether current market conditions warrant the ‘bubble’ descriptor.

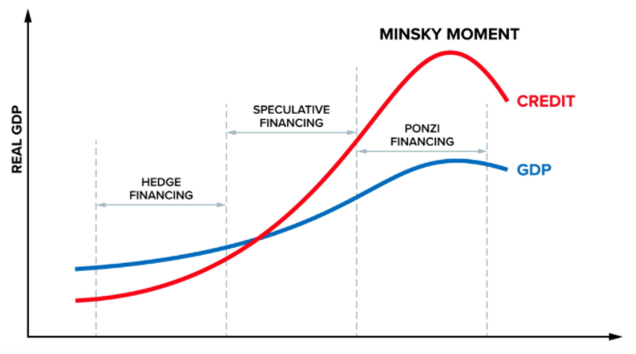

Economist Hyman Minsky developed the "Stages of Financing" within an economic cycle, culminating in a Minsky Moment. He described how a period of stability can lead to increased risk-taking and ultimately to a market collapse.

Figure 1. Stages of financing

The blue line in Figure 1., represents real Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while the red line reflects the relative level of credit growth.

Initially, the economy is characterised by "hedge financing," in which borrowers meet all their debt obligations with cash flow. This is often because very little debt has been adopted. In the early stage of a boom, the surrounding hype pushes share prices up, enabling companies to finance the scaling of their dreams through equity issues. As the cycle progresses, however, companies at the centre of the hype switch to debt, and as the debt accumulates, "speculative financing" becomes dominant. This is where borrowers can cover interest but must refinance the principal.

In Minsky’s final stage "Ponzi financing" abounds. This is when borrowers can’t even cover interest payments and rely solely on rising asset values to service debt.

The "Minsky Moment" occurs when asset values collapse, leading to a sudden and major market downturn as credit levels sharply decline.

While we don’t yet appear to be close to a final Minsky stage, it is worth keeping an eye on OpenAI. The company has forecast this year’s $US9 billion loss will grow to $US74 billion by 2029. At that point, debt will be materially higher than it is today.

In the language of finance, few terms are as frequently debated – and as poorly understood – as ‘bubble’. Usually, definitions compare quantitative overvaluation with qualitative behavioural mania, but an issue remains: a bubble is only truly confirmed post hoc – by its collapse.

We can’t rely on hindsight to navigate the present, but history provides a library of exuberant periods of excess to help diagnose current market conditions. By repeatedly spinning the bottle, I cannot help but be concerned that it keeps pointing to a convergence of valuation distortion, liquidity saturation, and a hazardous fallacy about competitive capitalism.

The fallacy of exceptionalism – this time is not different

The clearest signal of a late-stage cycle is a breakdown in the logic of competition. In a functioning market, capital discriminates between winners and losers. In a bubble, that discrimination vanishes.

In late 2025, we observed a market where an entire sector was priced as if the concept of ‘laggards’ had become obsolete. When the valuation of a sector’s third-tier competitors rises in lockstep with that of the market leaders, investors have succumbed to a fallacy of composition. They implicitly assume that aggregate earnings can expand infinitely to justify the pricing of every constituent in the sector.

This is a mathematical impossibility. When the forecasted summed earnings of an entire industry exceed the Total Addressable Market (TAM) of the broader economy, we have left the realm of investing and entered a period of collective fiction.

That began in late 2025. AI companies can’t all win. The AI theme might be perceived to be ‘structural’, but AI customers are ‘cyclical’. Customer appetite for AI tools will be determined by their price as much as, or even more than, their utility.

Meanwhile, hyperscalers and their data centre dreams will also eventually face a cyclical commercial reality that includes construction delays, energy price spikes, blackouts, brownouts, and drought. Already, Australian state government ministers are questioning the data centre aspirations of an industry that demands 20% of Sydney’s water supply be utilised for cooling.

The quantitative dislocation

The classic definition of a bubble – a decoupling of price from intrinsic value – remains the bedrock of bubble identification. Metrics like Robert Shiller’s Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings (CAPE) ratio and John Hussman’s Market Cap to Gross Value Added (GVA) were developed to strip away cyclical noise and reveal these structural distortions.

In the Dot-com boom valuations hit triple-digit multiples of sales for companies with negative operating margins. At that point, the market was no longer discounting future cash flows; it was discounting a utopia that could never materialise.

Have we reached that stage yet? Perhaps not. Measurably extreme valuations are the product of extreme behaviour. So, while metrics quantify the bubble, psychology fuels it. Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger famously mapped this pathology not as a static event, but as a five-stage dynamic process: displacement, boom, euphoria, profit-taking, and panic.

And as Figure 2., (no doubt inspired by Sir John Templeton’s aphorism that “bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on scepticism, mature on optimism, and die on euphoria”), reveals, AI investors might be optimistic, they may even be excited and greedy, but are they euphoric? I think not.

Figure 2. The mood rollercoaster

Source: Northwestern Mutual

The ‘Greater Fool’

John Kenneth Galbraith, in his seminal work The Great Crash 1929, best captured the point of no return. Galbraith identified the peak of a bubble as the moment when the utility of an asset – its income or the value of its use – becomes ‘academic’, and the only remaining value proposition is the asset’s price velocity. If buyers are acquiring an asset not because they care about its underlying value, or its usability to them, its long run worth, nor its income, but only because it’s likely to ‘go up’ more, Galbraith suggested you have already reached the summit.

His idea is formalised in the "Greater Fool Theory": the belief that valuation is irrelevant so long as liquidity remains deep enough to provide a greater fool with even more money to purchase the asset from you at an even higher price.

It’s most evident in the market for abstract vehicles of speculation – meme stocks, Pokémon cards and even altcoins. We see it today in the betting markets of Polymarket and the speculative fringes of the crypto-asset class, but because these ‘assets’ aren’t on the balance sheets of systemically important financial institutions, they might be at best a hint of excess liquidity.

The liquidity trap and the AI CapEx paradox

Finally, we should address the fuel source. A growing body of academic literature suggests that bubbles are less a product of optimism and more a function of excess liquidity.

The U.S. housing bubble of the mid-2000s was not driven solely by a desire for homeownership, but by a global savings glut and artificially suppressed interest rates that sought a yield-bearing home. Similarly, the Japanese asset bubble of the late 1980s – where the Imperial Palace grounds were theoretically worth more than all real estate in California – was driven by corporate cross-holdings and easy credit, creating a feedback loop of collateral value.

Today, it seems, we face a similar "irrational exuberance," to borrow Alan Greenspan’s phrase, but with a technological twist. We are witnessing record global liquidity chasing that singular AI narrative.

The concern for investors is not whether AI is real – the internet was real in 1999, too –but whether the economics work. We are currently seeing massive capital expenditure (CapEx) that requires a generation of revenue to justify. The global economy simply may not possess the capacity to generate the revenues required to recoup these investments on the timeline the market has priced in.

The outlook for 2026

While there are clear signs of enthusiasm and excess, we haven’t reached the euphoria evident in past manias. For that reason, I don’t believe we’ve entered a bubble. Of course, we cannot know until it has burst, and markets can correct at any time. After three very good years for equities, the higher prices, higher valuations, and the irrational belief in the smooth north-easterly expansion of AI adoption suggest 2026 could be more volatile than past years.

We have been bullish for three years, but in 2026 we adopt a more cautious outlook. The response? Rebalance your portfolio as you do annually, to take your asset class weightings back to those that reflect your risk appetite and financial circumstances and needs.

In other words, if equities were once 60% of your portfolio and, because of their strong absolute and relative performance, now represent 70% of your portfolio, bring the weighting down to 60% by reinvesting in other asset classes.

For what it’s worth, I’d consider a judiciously selected private credit fund, one without property developer exposure, a short duration book of underlying loans, at least monthly liquidity, no lockups, earning 6-9% per annum and producing monthly cash income. Alternatively, a market-neutral arbitrage fund with a track record of double-digit returns. Whatever you choose, seek to diversify those equity profits into funds with little or no exposure to public markets.

In 2026, there could be the odd bump.

Roger Montgomery is the Chairman of Montgomery Investment Management and an author at www.RogerMontgomery.com. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.