Stock markets have been shaky of late and talk of an AI bubble is rife. Bubbles don’t normally pop when everyone is talking about them and they also have a bad habit of going on for longer than most people think and/or can endure.

Stepping back from the daily noise, it’s clear that this AI bubble is different. The Magnificent Seven stocks are stupendously profitable, which makes them unlike the profitless tech names of the late 1990s. And their valuations aren’t nearly as high as those of the internet bubble or other bubbles.

The concern with the Magnificent Seven is about the sustainably of their magnificent profits and margins. Competition is heating up in the battle for AI supremacy and the companies are spending hundreds of billions of dollars on what could be a winner take all contest.

Recently, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg said that an AI bubble is “quite possible” though the larger risk for his company is hesitating.

"If we end up misspending a couple of hundred billion dollars, I think that that is going to be very unfortunate, obviously," he said. "But what I'd say is I actually think the risk is higher on the other side."

Increasing competition and investment normally lead to eroding margins and earnings. That hasn’t happened yet, but investors are focusing more on this and that’s led to some of the recent market volatility.

It’s not just the Mag Seven

There might be more of a worry with the valuations of smaller tech stocks. The only one of the Magnificent Seven that looks ludicrously expensive is Tesla, which is trading at a trailing price to earnings (P/E) ratio of 279x, though it’s been exorbitantly priced throughout most of its history.

There are lots of smaller tech names at mind-boggling valuations. For instance, leading AI business, Palantir, is trading at 106x revenue. It might be a good company but that valuation will be almost impossible to justify.

It’s not just tech in the US where prices seem high; it’s broader than that. Take large retailers such as Costco and Walmart. Both superb companies though they’re trading on PE multiples of 49x and 36x respectively. That’s a headscratcher given that they’re mature companies with slow and steady growth.

Outside of stocks, there’s been plenty of speculative activity too. Until lately, Bitcoin had been the best performing asset for almost any time frame over the past decade.

Gold had its moment in the headlines as people started queuing at ABC Bullion in Martin Place, which marked a peak in the yellow metal’s price, at least for now.

Residential property prices in Australia have popped up again, thanks to lower interest rates and the government’s ludicrous subprime mortgage scheme – I mean, 5% deposit scheme. The big question is whether momentum will stall if rates don’t go down further.

And private assets have also grabbed the limelight as money pours into the space. Cracks have emerged in this asset class though as some large private debt deals turn awry and private equity, especially funds that raised money and bought assets when rates were ultra-low in 2020-2021, is being forced to sell some of these assets at knock down prices (so-called ‘secondary’ sales).

Given the amount of money sloshing around and resulting speculative activity, it’s hard to believe that central banks are cutting rates. But that’s what they’re doing and the US is likely to cut much harder when Trump gets his nominated US Federal Reserve Governor in by May next year. Trump has openly stated rates should be much lower and the new Governor is unlikely to let him down (Fed independence be damned).

That’s what markets are betting on and why they may continue to go higher. At least for now.

Where to hide?

That begs the question about the best places to hide if you think a storm may be brewing. And that’s not an easy one to answer.

Cash is an obvious place to go. It offers the advantage of being liquid and can be deployed if markets go down. The disadvantage is they earn little to nothing, and after inflation, you go backwards.

Fixed term deposits are a favourite for many people. The rates for these deposits have started to tick back up, with expectations that the RBA may be done with cutting rates. So, the largest bank, CBA, is now offering fixed term deposit rates of 3.4% for six months and 4% for 12 months. My own go-to, Judo Bank, has rates of 3.9% for six months and 4.4% for 12 months.

The disadvantage with fixed term deposits is they’re taxed as income. Post tax, they aren’t going to earn you much after inflation is taken into account (especially after the latest inflation reading).

Bonds are hated by almost everyone right now, and that piques my interest. Every survey of institutional and retail investors suggests bonds have significantly decreased in asset allocations.

However, I suggested for more than three years that bonds are in a structural bear market, and previous bond markets have lasted about 30 years on average. We might be only five years into this one.

Therefore, while bonds might warrant a larger allocation in the short term, I remain negative on the asset class in the long term.

Turning to higher risk assets, not all equities and equity markets are frothy. The one area that stands out to me is value stocks. I’ve said it before but there are very few value-oriented fund managers left in the business. Most have been driven out as value has spectacularly underperformed growth stocks since the GFC.

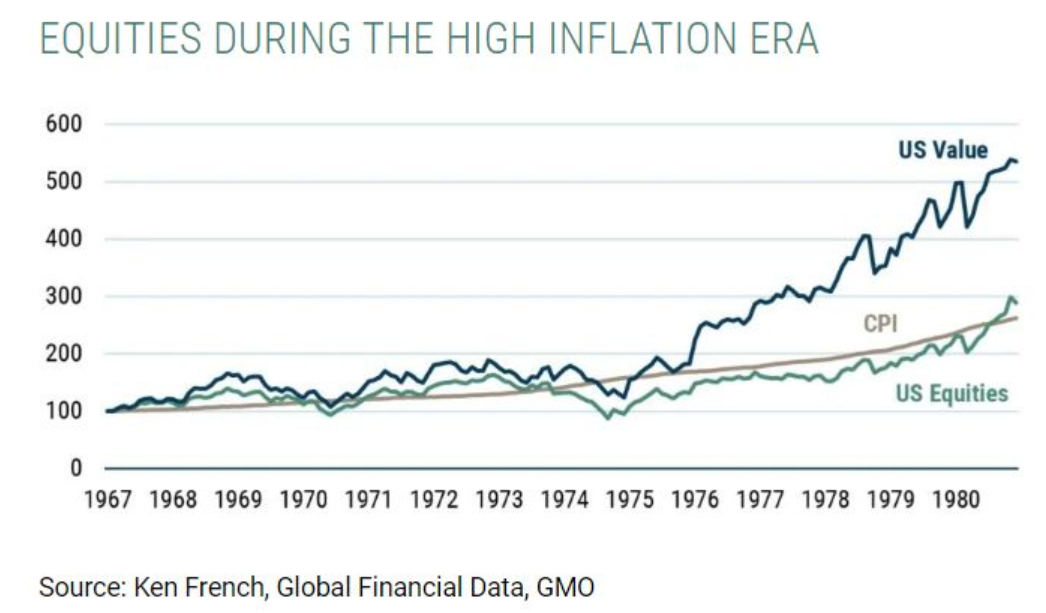

It’s worth noting that during other periods where this happened, value subsequently got its revenge. In the inflationary 1970s, US value stocks trounced the index and their growth counterparts.

A similar thing happened in 2000-2001.

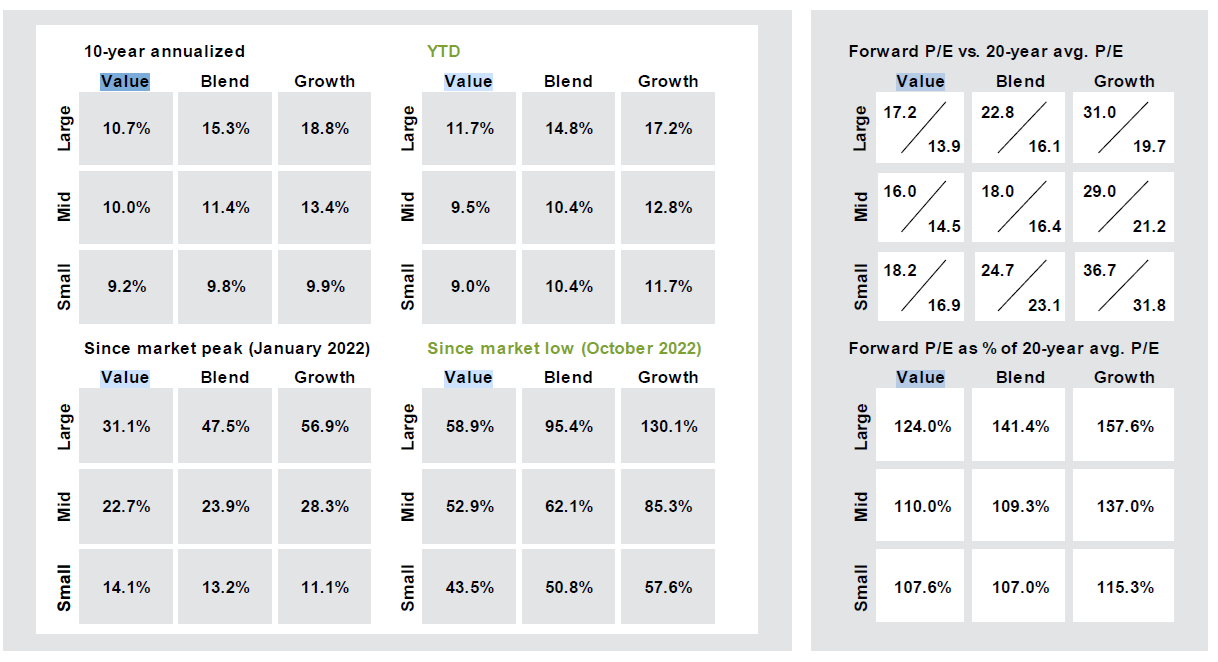

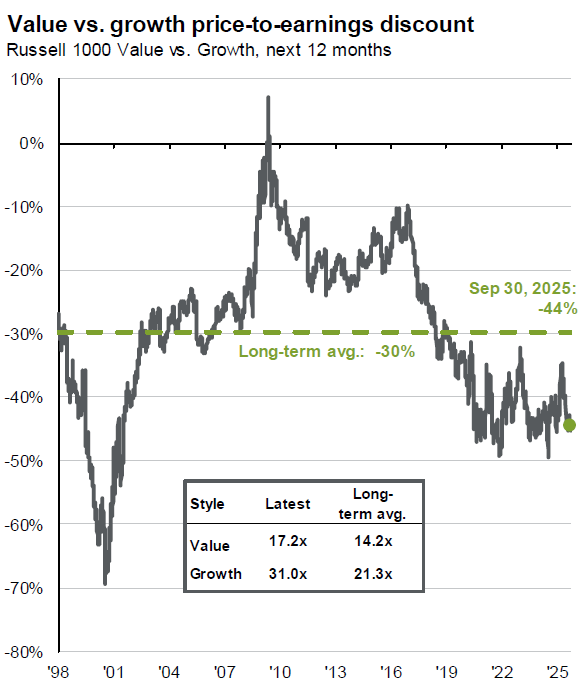

Today’s set-up for value stocks again looks interesting. Value has significantly underperformed growth and valuations look reasonable. The following charts show the breakdown for US stocks.

Note: As of end-September 2025. Source: JPM

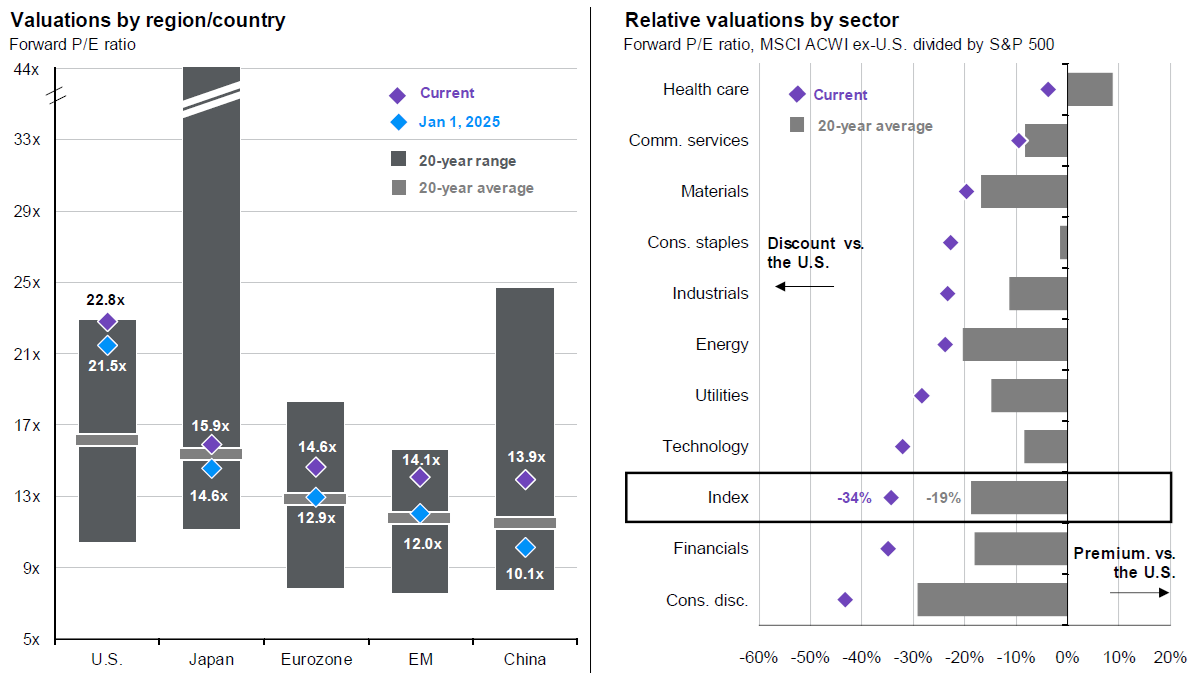

Outside of the US, stocks aren’t as expensive. They’re not cheap versus history, though they aren’t extended as America’s. It’s fascinating that South Korea, a perennial global market laggard, is up 61% year-to-YTD, crushing even the likes of the US. Which goes to show that while everybody crowds into the US and US tech, there are opportunities elsewhere.

Note: As of end-September 2025. Source: JPM

On private assets, I am a sceptic. The main problems I have with them are around liquidity and transparency. Private equity and private debt are the private variations of public equity and public debt. That may sound obvious yet isn’t mentioned enough. And while public equity and debt often offer daily pricing and daily liquidity, most private equity and debt don’t. So, unless you’re compensated for the extra risks of holding private equity and debt, it may not be a great deal for retail investors.

As for other ‘alternative’ assets, I recently wrote about how I’d held gold for 17 years and had been selling down, especially as people started lining up to buy physical gold. I still hold some gold primarily as a hedge against government and central bank stupidity, but what worries me is the gold price has been going nuts alongside stocks, and if stocks swoon, gold may not be the portfolio diversifier that it has been in the past.

On Bitcoin, Charlie Munger described it as ‘rat poison’, and I don’t think he was too far wrong. I question what it’s useful for, other than being a conduit for scammers and criminals.

What to do with your portfolio?

Stress testing your portfolio makes a lot of sense right now. Would you be comfortable if global stocks went down 50%? Which areas would be most at risk if that happens? Perhaps you’re overweight US and particularly US tech stocks - could it be time to dial down some risk? Is your portfolio truly diversified?

If you’ve set up your portfolio right, it might be best to do nothing. If you haven’t, hopefully my suggestions can prompt ideas for tinkering, if necessary.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.