One only needs to glance at a map of the US equity market to determine ‘we’re not in Kansas anymore’. The era of network economics and ever greater financialisation has wrought massive change on equity markets and increasingly on the real economy.

Ever-growing government deficits and strong ongoing growth in household borrowing are funding a relatively buoyant profit environment, albeit one that is distributed increasingly unevenly. Disequilibrium is becoming the norm and the economic forces which tended to work against this are proving ineffective. While the reasons for this ongoing disequilibrium are debatable, a few seem important.

Network economics

While the line between network economics and monopolies is often blurred, many of the world’s largest companies control ubiquitous products or services where extremely large customer bases make it exceptionally difficult for new competitors to challenge, imputing massive pricing and market power. Additionally, this market power is global rather than domestic. Large US companies have done a very good job of stripping profit from the rest of the world, albeit owning shares in these companies has transferred a fair amount of the dramatic increase in asset value back to shareholders all around the world. Relatively small employee bases and few tangible assets have seen vast profits and minimal taxation given the difficulty of trapping tax in the same jurisdiction as revenue and the propensity of very small tax havens to relieve larger countries of tax revenues by offering vastly lower tax rates. To date, capital expenditures from these companies have been minimal. This is changing markedly as a result of AI, a business only tangentially related to the areas in which major technology companies have made their historic profits. These technology behemoths are increasingly competing with each other. They are also competing in this race with China.

Chinese competition

Industries directly subject to competition from China have seen profits and return on capital erode materially over many years. Labour arbitrage, massive scale, lower safety, emission and pollution standards together with government subsidies are a headwind for even the most efficient companies. As is often quipped, when China enters a market the profit often disappears. In capitalist economies this creates a problem. When there is minimal profit and low returns, reinvestment disappears. Manufacturing and processing industries have largely disappeared while most retailers rely almost totally on Asian production. Western economies have gradually become ever more services and consumption reliant.

Monetary intervention

Keen to display the power of monetary intervention in ‘smoothing’ economic cycles and preventing any downturn, central bankers everywhere have ensured additional credit and easy monetary conditions have accompanied any sign of slowing. Low goods inflation which had nothing to do with Western economy productivity was the rationale for ever lower interest rates, while service economy inflation remained relatively high and was becoming an ever larger proportion of the economy. Credit was funnelled into consumption and housing inflation rather than improving the capital stock and infrastructure. ‘Smoothing’ cycles meant the tough times which normally promote cost shedding and efficiency gains together with the bankruptcies which normally cleanse weak performance and excessive leverage have been absent.

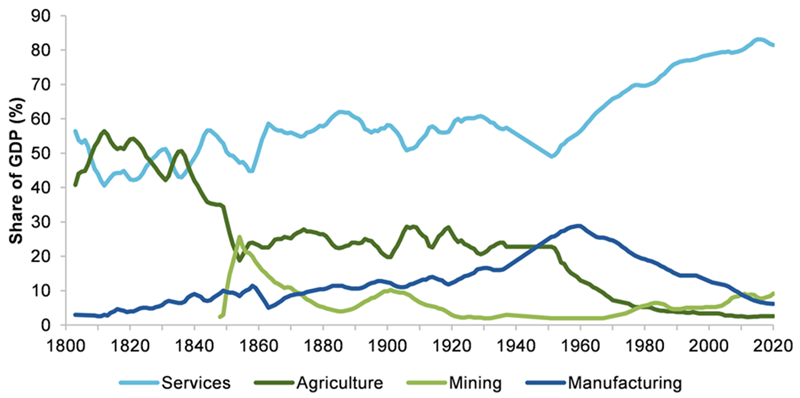

Against this backdrop, Australia has many similarities and some differences with the US and other Western economies. Listening recently to one of the always excellent podcasts of Joe Walker, Joe was talking to Greg Kaplan and Michael Brennan about the structure of the Australian economy and productivity decline. In thinking about the outlook for Australia and its companies relative to the rest of the world, it is crucial to understand the key differences. As Michael Brennan highlighted, there are three areas in which Australia is quite different. The first is mining. As has been highlighted in recent months, the extraction of raw materials on which the world relies is a small but crucial sector in the global economy. It is much larger in Australia, meaning commodity prices have an outsized influence. The second is financial services. A voracious appetite for housing debt and a large and non-government superannuation system result in a significantly oversized financial services sector relative to other economies. The third is construction. As a much higher immigration country than almost all Western counterparts, resulting in significantly higher population growth, construction is a much larger sector of the Australian economy. Agriculture is another sector in which Australia is disproportionately large (and incredibly productive), albeit one in which equity market exposure is limited. On the other side of the equation, manufacturing is a much smaller sector in Australia. While the abovementioned impact from China crushing profitability has been important for the world, its impact on Australia has been markedly narrower.

Source: Productivity Commission – ‘Things you can’t drop on your feet’ – April 2021

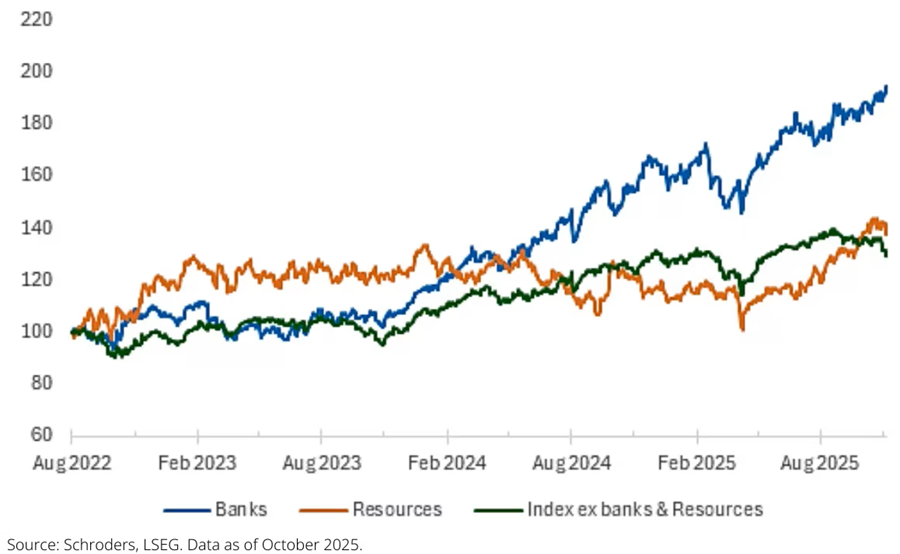

Observing the market map of the domestic equity market starkly highlights these differentials, particularly in mining and financial services. The fate of these sectors will always have a disproportionate impact on returns for domestic equity investors.

In looking at these sectors in turn:

Financial services

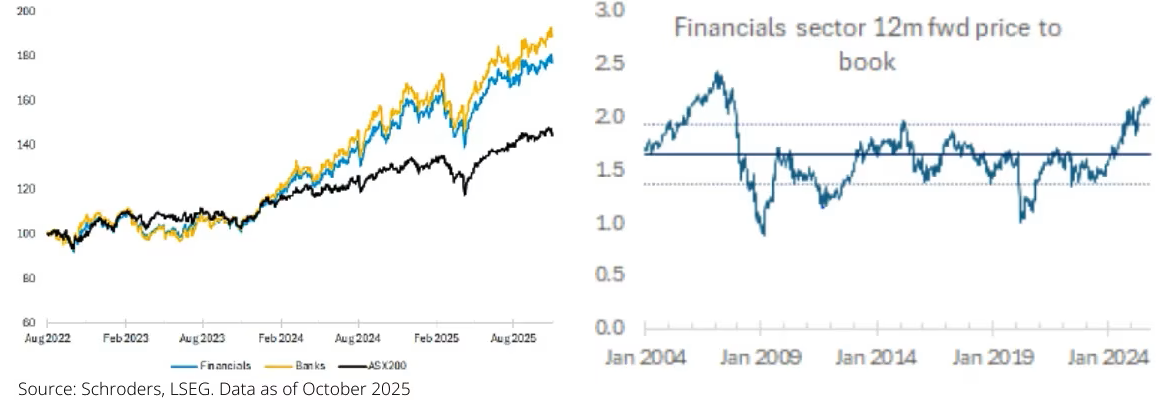

Recent years have been good times for financial services, at least in equity performance terms. As the charts highlight, strong outperformance has been driven by expansion in PE and price to book multiples rather than strong earnings growth, leaving multiples very high versus history. While CBA and Macquarie contribute disproportionately to this position, and remain in our view, the most overvalued constituents, the rising tide has seen optimistic valuations permeate much of the sector. Revenue conditions have been polarised. While banks have seen increasing commoditisation and competitive conditions suppress revenue and profit growth, despite reasonable volume growth, insurers have enjoyed booming revenue conditions as rising construction and labour costs were passed on to consumers and large players chose to slowly shed market share and enjoy the easier gains through raising prices. We’d expect conditions are far more likely to become tougher for insurers over coming years. Banks sit at a crossroads and recent discussions with the incoming ANZ CEO, Nuno Matos, provide some interesting perspectives from an experienced banker with global perspective. Cost structures are bloated, technology and consulting companies have feasted on bank bureaucracy, mortgages from brokers don’t make money and the exit of banks from wealth management after the Royal Commission was misguided. More of the same from the sector seems unlikely.

Resources and energy

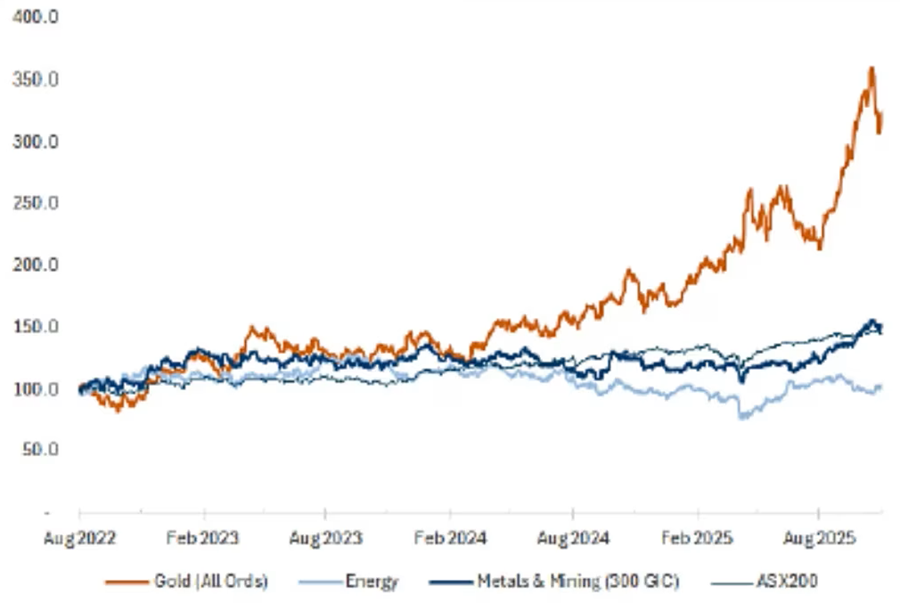

The resource and energy picture is more nuanced. While the sector overall has performed largely in line with the broader market, gold has contributed the outperformance and energy is the other side of the equation. While more durable measures of value such as price to book leave the materials sector at around average levels and the energy sector near historic lows, gold is again providing upward impetus to valuations in the materials sector. While narratives around gold price performance remain abundant and almost universally positive (store of value, inflation hedge, protection against fiat money collapse, portfolio diversifier – it’s got the lot), bottom-up valuation measures would urge more caution. Energy is perhaps the reverse. Plentiful supply, fading demand with decarbonisation, less than rational supply response from OPEC and producers – not much in the way of positive news. Bottom-up valuation again sends the reverse signal. Valuations near book value, little incentive to invest and increasing geopolitical tension would suggest endless negative momentum might eventually run out of gas (I’ll be here all week)! While the picture across commodities is polarised, with gold and critical minerals flavour of the month, energy the reverse and iron ore, aluminium and many others somewhere in between, we remain very positive on stock selection opportunities and seemingly large valuation gaps in many areas.

Construction

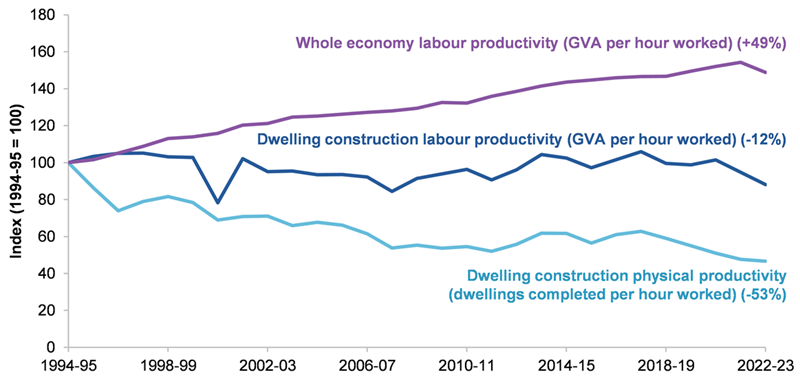

While a major sector of the Australian economy, equity market exposures to the sector are disproportionately in owning real estate rather than building it, the economy remains inextricably linked to it. Our long-term concerns on the unsustainability of the sector remain, albeit acknowledging policy continues to defer the likely realisation of these concerns. Despite housing starts per capita well above nearly every other Western country, the prevailing narrative remains one of a ‘supply’ problem. As evidenced in NZ over recent times, where falling immigration has extinguished upward price pressure, the demand tension from very high immigration is far more likely to be the material driver in this equation. While our views on misguided immigration policy will obviously have no impact on the outcome of policy which seems to believe in government controlled population ageing outcomes, ever more extreme property prices will become ever more sensitive to changes in the immigration outcome, regardless of whether they are exogenous or endogenous. We remain vastly more concerned on price over volume. Construction material exposures seem unlikely to experience volume decline given poor construction productivity has seen the sector unable to keep pace with immigration fuelled demand for many years. The accumulated deficit should sustain a solid demand environment for many years, with any eventual adjustment more likely to be felt in land pricing.

Source: Productivity Commission – ‘Housing productivity – Can we fix it?’ – February 2025

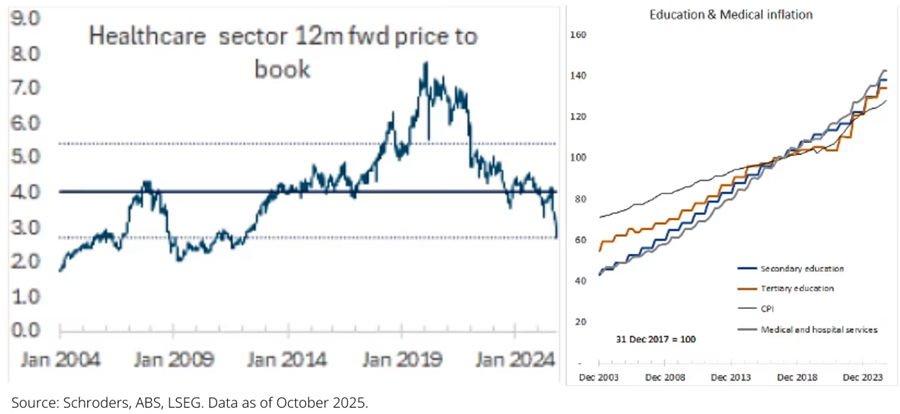

Outside the disproportionately represented sectors of the economy, we’d observe a number of areas which offer opportunity for those inclined to wager that disequilibrium might not be the natural state of affairs. Possibly the best example is in the healthcare sector.

If one is inclined to search for opportunity in the downtrodden, one needs look no further. Across private hospitals, pathology and pharmaceuticals, the list of former darlings in the doghouse is long. Distortions from COVID, doctor shortages, rampant cost escalation and competition from out of control NDIS spending are amongst the long list of reasons the sector is under both profit and equity market pressure. The private health insurance sector which serves little function beyond acting as an intermediary between community-rated premiums (code for being tax rather than insurance as the young and healthy subsidise the elderly) and healthcare providers, commands vastly more market capitalisation than the hospitals providing the service (currently about $13.4 billion for Medibank’s 27% share of the private health insurance industry versus $7.2 billion for Ramsay Healthcare’s similar market share in Australian private hospitals (we’ll ignore the rest of the Ramsay business and assume it’s worthless). CSL, Sonic Healthcare, Healius and Australian Clinical Labs have all had similar share price patterns. While the current margin squeeze may not abate in the short-term as the government aggressively exacerbates cost inflation through NDIS spend and public sector wage inflation while simultaneously constraining healthcare outlays to others in an attempt to fund their own largesse, something will need to give in the longer term. We’d expect this is some combination of improved funding and foisting onto the user an increased share of healthcare funding. We see plenty of opportunity for the longer-term focused.

The landscape remains one of aggressive but still bifurcated valuations. In many cases we’d perceive it is not the best companies commanding the highest valuations. Short-term earnings growth and enticing narratives in areas such as defence, critical minerals and AI are being met with far greater fervour than business sustainability. Skewing portfolio holdings towards real economy businesses less susceptible to disruption and replete with far more underlying asset value can be accomplished whilst simultaneously paying far lower multiples. Just as the narratives around the urgent imperative to shift all business to the cloud for fear of being the last remaining dinosaur in Jurassic Park proved a wild exaggeration seeing far too many companies cede both profits and control over their own destiny to US technology giants, AI seems to call for cool heads and considered decision making rather than lemming behaviour and ludicrous forecasts. In markets in which efficiency is equated with speed, quantity of data collection and wild overreaction rather than considered thought, we believe the payoff for the latter is becoming greater.

Martin Conlon is Head of Australian Equities at Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article does not contain and should not be taken as containing any financial product advice or financial product recommendations. It does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.