Recessions do not naturally begin in an economy with two job openings for every job seeker. That said, there’s nothing natural about recessions. In 1998, MIT Economist Rudi Dornbusch in the US observed that “none of the post-war expansions died of natural causes, they were all murdered by the Fed.” The motive for this murder is usually to save the economy from incipient inflation by killing the economy.

It is a time of heightened uncertainty, with many forces driving that uncertainty. The US has an inflation rate at a four-decade high. Most people don't remember the last time inflation was at this level. The Fed's responses adopted now will likely slow the economy. The Fed is very late to the game because the board members were in denial for a long time. In November 2021, the Fed finally officially retired the word transitory after dismissing the inflationary pressures with that description far too long. We might be surprised that the Fed did not see this coming, but the Fed’s track record on forecasting, whether the economy or inflation, is rarely better than a Ouija board.

Inflation’s causes, prospects, and the Fed’s toolkit

Inflation is a simple consequence of a supply/demand imbalance. If demand exceeds supply, prices rise until balance is restored. The current surge in inflation has been caused mainly by blowout spending, supply chain disruptions - some related to Covid lockdowns and some to geopolitics - the Russia-Ukraine war, and working from home, which leaves people with more money to spend, even as many produce less goods and services.

Which of these can the Fed influence? None? Is the Fed powerless to rein in inflation? Not at all. Central bankers can decrease demand, albeit with serious lags, even if the problem is on the supply side.

To a person with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. With an echo-chamber guiding monetary policy all over the world, the only answer that seems to resonate with central bankers is to decrease demand. None of this is to say that the Fed should continue with a dozen years of negative real rates. Jerome Powell inherited a Fed after a half-dozen years of negative real interest rates, which he has continued to this day.

We liken real interest rates to a speed bump. Too high and traffic is stopped: innovation, long-horizon investment in new initiatives, entrepreneurial capitalism all slow markedly. Too low and reckless driving ensues: if we are among those able to borrow at negative real rates, we will, whether we have good ideas for the money or not. Misallocation of resources and malinvestment - at the individual, corporate, and government level - naturally will follow, along with propping up zombie companies that clog the runway for the innovators. All of this in turn inhibits innovation and entrepreneurial capitalism, both because risky projects cannot access those ultra-low rates, and established enterprises and government may waste much of the free money at their disposal.

Being late to the game increases the probability that the Fed overreacts, because it didn't act soon enough. This increases uncertainty and elevates the probability of a hard landing, which is what everybody wants to avoid. Hard landing means we go into a serious recession, like the one associated with the GFC. There are huge economic as well as human costs associated with hard landings. Nobody wants to be laid off or to spend an extended amount of time on unemployment insurance. A soft-landing scenario is much more desirable. That could mean slower economic growth or maybe a mild recession before the economy moves into a recovery phase.

Will the Fed raising interest rates by 75 basis points make a difference to supply chain disruptions? No. To deal with inflation, we need to deal with the source of the problem and address it directly, not just hit it with a blunt instrument that sometimes worked in the past. The usual approach does not inspire confidence. We worry the Fed is going to mess it up.

Step number one is to go through the individual components driving the 8.6% CPI inflation number. Consider housing, for example. Given that a homebuyer can get a mortgage for much less than 8.6% means that effectively the financing is free or being subsidized. In terms of real rates, this increases the demand for housing. So, for this component, raising rates appears to have some logic. But the housing issue is much more complex, encompassing not just the demand for mortgages, but the demand for materials, and the structural backlog caused because we have not been building enough housing over the last five years. The rise in housing prices has nothing to do with Covid.

The near-term prognosis for inflation is not good

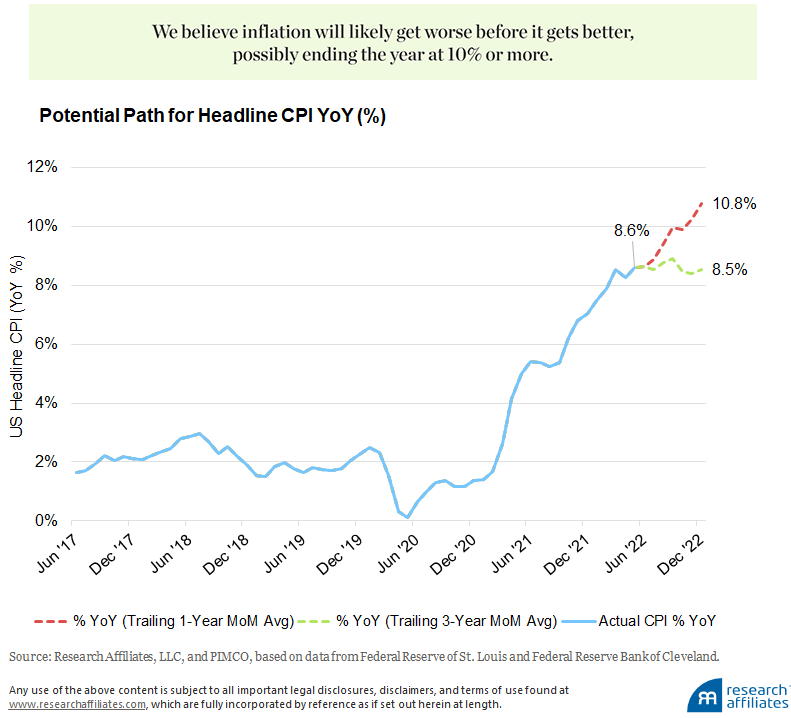

Each month’s 12-month inflation rate matches the previous month’s inflation rate, plus a new month, minus the corresponding month dropped from the previous year. We can’t know with any confidence what the new month’s rate will be, but we know with precision the rate of the month being dropped. The next four months to be dropped from 2021 will be 0.9%, 0.5%, 0.2%, and 0.3%, respectively.

The Cleveland Fed produces an 'inflation nowcast' which estimates what the monthly inflation would be if the month ended today. If their nowcast is correct, the 0.9% from June 2021 will be replaced with 1.0% for June 2022. If inflation in each subsequent month through year-end 2022 matches the average inflation rate over the prior 12 months, we should finish the summer at 9.9% and finish the year at 10.8%.

If, alternatively, monthly inflation recedes to match the trailing 36-month average, then the current 8.6% inflation rate would remain steady through year-end. This simple analysis leads us to believe that inflation will likely get worse before it gets better.

There’s another problem with the way CPI inflation is calculated. The largest component, shelter, is one-third of the total and is smoothed and lagged. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), their chosen measure for the cost of home ownership, owners’ equivalent rent (OER), is up 7.3% in the last two years, while the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index shows that US home prices have risen by 37% in the two years ended March. The BLS switched to OER after the last inflationary surge in 1979–81; indeed, if inflation was calculated today like it was in 1981, we would already be solidly into double digits.1

The one-third of CPI for shelter will be playing catch-up for some years to come. Empirically, most of that catch-up occurs over the subsequent two to three years. Note that this inflation has already happened; it simply hasn’t made its way into CPI quite yet.

Preparing for recession versus reacting to recession

Uncertainty is a negative force and is a question of degree. When a war is going on, especially involving a nuclear power (as is the case now), that's a big deal, much different than a regional war that doesn’t involve a nuclear power. The degree of uncertainty is key. An average level of uncertainty is always present, but the level can fluctuate. When the level of uncertainty is relatively high, as it is today, business leaders should actively manage their risk.

What does risk management look like? Let’s say, for instance, that a corporation has a promising project which entails building a new plant. Management believes this investment will enhance its long-term value. It increases investment, employment, economic growth, all good things, but the corporation needs to finance the plant. At this point in time, do you want to bet on the company given the current uncertainties? This isn't theoretical. With inflation running at a 40-year high, major geopolitical disruptions around the world, monetary and fiscal policies in flux, the logical tactic is to exercise caution.

In his 1986 PhD dissertation, one of us (Cam Harvey) was the first to show that a yield-curve inversion has a perfect batting average in forecasting recessions since 1968. The other (Rob Arnott) has suggested that a yield-curve inversion doesn’t predict recessions, it causes recessions. The long end of the yield curve is mainly a market rate set by the market’s perception of the fair cost of long-term capital. The short end is largely managed by the central bank.

If the central bank raises the short-term cost of risk-free capital above the long end, it is choosing a rate the market tells us is too high. This isn’t necessarily the case in an economy (Europe or Japan) where the central bank also controls the long end of the yield curve (in policy circles, this is called yield-curve control). But, when the free market determines the long end of the yield curve, the Fed should pay close attention!

On 30 June 30 2019, when the yield curve had inverted for a full quarter, Cam was frequently interviewed by the media, explaining that this signal was 'code red' for recession. All previous eight episodes since October 1968 of inverted yield curves were followed by recessions, with no false signals. Some criticized his statements as potentially causing a recession. No, his warning was risk management 101. Facing a red flag, a business would be ill-advised to bet the firm on that new plant.

Today, the yield curve is not inverted, so why worry? As with the recent two-fold surplus of job openings relative to job seekers, this too shall pass. Really? The forward markets do a pretty good job of forecasting near-term Fed decisions and they are suggesting a 90% likelihood of a 75 basis-point hike in July followed by another 50 to 75 basis points in September. Those moves would take the 3-month Treasury bill yield to about 3%, within hailing distance of the current 3.15% yield on the 10-year Treasury bond. Absent a run-up in long bond yields, one additional hike before year-end would leave us with an inverted yield curve. Further, Cam's analysis shows the slope of the yield curve is the key indicator. A flat curve is bad and an inverted curve is really bad for economic prospects.

Many companies took Cam’s warning in 2019 seriously, and indeed when Covid hit, they were in reasonably good shape. No single industry faced an existential crisis as a result of Covid, although some industries, especially hospitality, restaurants, and retailers, were more negatively affected than most. But this was not like the GFC when a single industry, financials, faced a risk of collapse and/or nationalization. Some people were ready because they knew an inverted yield curve was a reliable red flag. Today the heightened uncertainty is obvious. We think that means people will be cautious and they will engage in risk management.

It’s not too late to prepare

If we are not already slipping into recession, we see a substantial probability that a recession could start in late 2022 or 2023. If we are right, then the CEO of a company that gets into real trouble in the recession can't go on stage at the shareholders’ meeting or on the quarterly earnings call and say management was blindsided by the recession. That's not good enough. People would laugh at them. The signs of recession are in your face. The way to deal with it is to be more conservative until some of the uncertainty is resolved.

Rob Arnott is a Partner and Chair, and Campbell Harvey, PhD is a Partner and Head of Research at Research Affiliates, LLC. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any person.

Footnote

1. In "The Coming Rise in Residential Inflation" available on SSRN, Bolhuis, Cramer, and Summers (2022) argue that "the current inflation regime is closer to that of the late 1970s than it may at first appear."