This is Part 1 in a three part series on capital allocation and management ability.

Many years ago the world’s wealthiest man Warren Buffett said that growth was not always a good thing. What? Aren’t companies of the western world doggedly pursuing growth? If our economy has two quarters of negative growth, we call it a recession and recessions are bad things. More sales, more profits, more products. It is all about ‘more’. But growth is not always good. They might not know it but for some investors, growth has destroyed wealth both quickly and permanently.

Remember ABC Learning Centres? April 2006. The shares were trading at more than $8.00 and profits were growing at a fantastic rate - they had risen from about $11 million in 2002 to over $80 million in 2006. The problem was return on equity was declining.

It is return on equity that will help you identify the great companies to safely invest in. And it is return on equity that will save your portfolio from permanent destruction.

To understand what Warren Buffett was talking about when he said not all growth is good, you need to know something about return on equity.

Imagine you have a business, even a good one. You invested $1 million dollars in it, bought a shop and in the first year, produced a real cash profit after tax of $400,000. That’s a 40% return. Now suppose another shop came up for sale in another area for $400,000 and you decided to buy it. As it happens you are really good at running the first store you bought but you have found running the second store a little harder. Traveling between them is a challenge and so you bring in a manager for the second store. The result is that after a year of owning the second store it produces a profit of $20,000. Meanwhile the first store produces another $400,000. The second store has generated a return of just 5%. Many business owners – and I know one or two – would say this is still satisfactory, because profits have gone up. In the first year your business made $400,000 and in the second year, profits have gone up to $420,000. Profits of your new ‘group’ grew by 5%.

Thinking about this situation another way reveals what a poor investment the second shop is. You first have to remember that you gave your business more money, so profits should have gone up. A rocking chair to sit in and a bank account are all you need to make profits go up. Invest $1 million in a bank account and then put in another $400,000 the year after and the interest you earn in the second year will be higher than in the first. You have grown the profits and it has been no effort at all.

So when a company increases its profits it is nothing spectacular if the owners have invested more money in the company. This is purchased growth. Shareholders have funded the opportunity for the directors to look good. The situation is even worse if that additional money generates a return that is less impressive than the rate available from a bank account. And if a higher return can be earned for the same risk or the same return for less risk, somewhere else, then the reality is that you don’t want to put more money into the business. You don’t want it to grow. It is better that the $400,000 is taken out of the business, rather than employed to purchase another shop. The $400,000 should be invested elsewhere at a higher rate or even at the same rate in a bank account, which has a lot less risk.

If, each year, you invested the $400,000 from the original shop into a new one that produced a return of 5%, the business would have many shops earning 5%, and each year the business would be worth less and less even though profits would be growing.

Many investors don’t understand this – that there is growth that will destroy wealth. They happily allow the management of a company to keep the money ‘to grow the business’ and willingly accept a low return. That low return is actually costing you money because you could have earned a better return elsewhere. It is called opportunity cost. Investing the money in the business at a low rate of return has cost you the opportunity of earning more or earning the same, but with more safety, elsewhere.

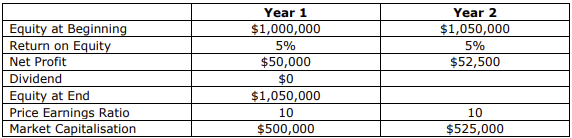

For example, the following table shows that an investor in a company that generates a 5% return on equity and that keeps all the profits for growth rather than paying those profits out as a dividend, will lose half their money.

Table 1: How to lose money despite profits and capitalisation rising

Table 1 shows a company listed on the stock exchange and whose shares are trading on a price earnings ratio of 10 times. The price earnings ratio is simply the share price divided by the earnings. So if the share price is $5 and the earnings are 50 cents, the price earnings ratio will be 10. It means that buyers of the shares are happy to pay 10 times the profits for the company.

In Year 1 when the company earned a profit of $50,000, the stock market was willing to pay 10 times that profit or $500,000 to buy the entire company. Another way of thinking about it is that the stock market thinks the company is worth $500,000. Of course, as we have talked about already, what the stock market thinks the company is worth and what it is actually worth are very often two different things. Don’t listen to what the stock market thinks.

The company begins Year 1 with $1 million of equity on its balance sheet and in the first year, generates a 5% return on that equity, or $50,000. Management decides that the money is needed to ‘grow’ the business and so no dividend is paid. As you are about to discover, that decision has cost shareholders a small fortune.

By keeping the profits, the equity on the balance sheet grows from $1 million at the start of the year to $1,050,000 at the end. In the second year, the company again earns 5% on the new, larger equity balance. A 5% return on $1,050,000 is a profit of $52,500.

So on the surface things look rosy. I’ll give you a week to think about what the problem is, and in Part 2 of this series next week in Cuffelinks, I’ll show you how shareholders have been dudded by management and company directors.

Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund.