While the latest Division 296 draft legislation may have dispensed with an unrealised capital gains tax component, it still has the whiff of a wealth tax about it. That’s because the effective tax rate on earnings, including any realised capital gains, is tied to the Total Superannuation Balance (TSB) and not just the earned income itself.

Though technically not a wealth tax, because you actually have to earn income to be exposed to Div 296, the larger the TSB, the higher the effective tax rate on earnings, which makes it feel like a tax related to wealth.

Outside of super, two people with the same income pay the same tax regardless of net worth. Not so under Div 296.

For example, an SMSF with a $4 million balance would pay $18,750 tax on $100,000 income. While an $8 million fund would pay $24,375 tax on that income.

Acknowledging these are large balances, they serve to make a point. That Div 296 applies higher rates to larger balances, perhaps achieved via longer working lives or superior investment performance. Div 296 is effectively a balance-based tax with a retrospective feel.

A simpler alternative could've done the job

Yet the Div 296 link to wealth could have been avoided by instead setting up a progressive super income tax system, working the same way as the taxation of income outside super. Tax would be triggered solely by income, with marginal tax rates increasing with income. Such an approach would be more transparent, mainstream, simpler, and easier to sell than Div 296.

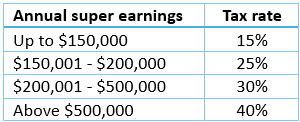

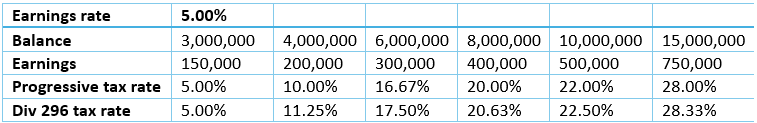

A progressive super tax schedule might look like the following:

This schedule assumes a ‘normal’ earnings year of 5% on fund balance. The 15% rate up to a threshold of $150,000 is therefore anchored to 5% earned on a balance of $3 million, aligning with the Div 296 threshold below which earnings continue to be taxed at 15%. The 25% rate on $150,000 to $200,000 is a transition zone, then the 30% rate (the second tier Div 296 rate) up to $500,000 corresponds to a 5% return on balances up to $10 million. And the top marginal rate of 40% thereafter reflects the Div 296 effective upper bound.

Note: this progressive schedule applies to member balances in accumulation phase. Where a member also has a pension-phase component, a progressive super earnings tax can be accommodated by introducing a tax-free earnings threshold equivalent to the maximum pension balance. For example, a pension component capped at $2 million implies a tax-free earnings threshold of $100,000 when anchored to a 5% return (see Footnote for a pension phase schedule).

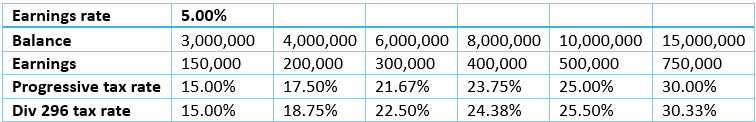

Let’s compare total effective tax rates on earnings under the progressive schedule versus Division 296:

Scenario 1: Earnings rate 5%

Example: $8 million balance, earnings $400,000.

- Progressive effective tax rate: 23.75% = ((150,000 x 15%) + (50,000 x 25%) + (200,000 x 30%)) / 400,000.

- Div 296 effective tax rate: 24.38% = 15% x (1 + (8,000,000 - 3,000,000) / 8,000,000).

Scenario 1 shows a close alignment between effective progressive tax rates and Div 296 rates. But importantly, balances play no role under the progressive tax rate structure. Marginal tax rates progress according to earnings. The 15% tax rate still applies for ordinary outcomes expected on balances up to $3 million. Most accounts would never leave the 15% bracket, while higher earnings are targeted with higher tax rates. The tax rate would be determined purely by income, and not super balance accumulated to date.

Though the resulting tax rates are closely aligned in Scenario 1, to understand the flaws inherent in Div 296, we need to consider a poor earnings year.

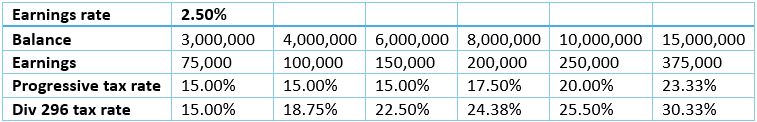

Suppose the yearly earnings rate is only half that of a ‘normal’ year, at 2.5%:

Scenario 2: Earnings rate 2.5%

Note, Scenario 2 Div 296 tax rates are unchanged from Scenario 1. That’s because those rates are driven by account balances, not earnings amounts. But the progressive tax rates in Scenario 2 have dropped from Scenario 1, due to the lesser earnings amounts. Any alignment in tax rates has vanished.

We see here that Div 296 is aggressive at low earnings on high balances, but that the progressive based system is more forgiving on lower earnings (and more aggressive on higher earnings). This doesn’t imply that the progressive system is too generous, rather that Div 296 imposes a higher tax rate on modest earnings when balances are large. That is, Div 296 is more onerous when returns are low relative to balances, but not when returns are strong.

Div 296 could therefore be seen to penalise more conservative portfolios. It’s as if it assumes large balances will generate high earnings, and it will tax accordingly, even if those earnings don’t eventuate.

So from a revenue perspective, ‘normal’ long-term return years should generate similar tax takes under both approaches. But in low return years, Div 296 will reap more revenue, while a progressive structure will collect more in high return years. Div 296 taxes regardless of performance, a progressive system is outcome-based.

In the end, Div 296 has the potential to penalise time and compounding. It is a complex tax, that uses existing savings as the basis for possibly higher tax rates.

Meanwhile, a progressive income-based tax structure avoids wealth-based proxies and debates around retrospectivity, and wealth taxes in general. It would be determined purely by income, and not balances accumulated to date. It would be administratively simpler and easier to explain, with no proportions of TSB above thresholds required. The messy design of Div 296 would be avoided.

Politics wins?

So what is the political motivation for Div 296 over a progressive tax system?

The political mood to address very large super balances is a core reason. It allows the government to argue that it is reining in ‘excessive’ tax concessions by taxing larger balances more. Even though on average, a progressive earnings tax would also target high balances, higher tax rates driven by income renders a weaker ‘excess balance’ narrative.

And while the calculation method and magnitude of those concessions are debatable, what is not is the use of the super system as a tax-preferred environment to accumulate and shield wealth.

Div 296 also provides more predictable revenue, with effective tax rates more stable when a function of account balances rather than volatile earnings. Though this comes at the expense of fairness in outcomes.

Overall, both systems would likely drive similar long-term incentives and revenue. But the question remains whether a golden opportunity for simpler and fairer super tax reform has been missed.

Footnote

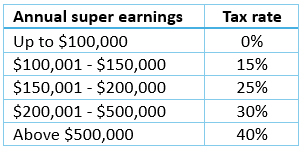

A progressive super tax schedule accommodating maximum pension account balance of $2 million:

The $100,000 tax-free threshold reflects a capped $2 million pension balance, anchored to a 5% assumed return.

Corresponding comparison to Scenario 1: Earnings rate 5%

Noting there is still strong alignment between progressive tax rates and Div 296 rates.

Example: $15 million balance, earnings $750,000.

- Progressive effective tax rate: 28.00% = ((100,000 x 0%) + (50,000 x 15%) + (50,000 x 25%) + (300,000 x 30%) + (250,000 x 40%)) / 750,000.

- Div 296 effective tax rate: 28.33% = 15% x ((15,000,000 – 2,000,000) + (15,000,000 - 3,000,000) + 2/3 x (15,000,000 – 10,000,000)) / 15,000,000.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.