Why is Prime Minister Anthony Albanese suddenly so keen to deliver extra cost-of-living relief? One immediate reason is he is keen to make sure Labor wins the upcoming byelection in the outer-Melbourne electorate of Dunkley on March 2. But the cost of living wouldn’t matter much for Dunkley – and it wouldn’t matter much for the rest of us – unless it was really biting.

And despite what the Treasurer himself has been trying to tell us, it is biting.

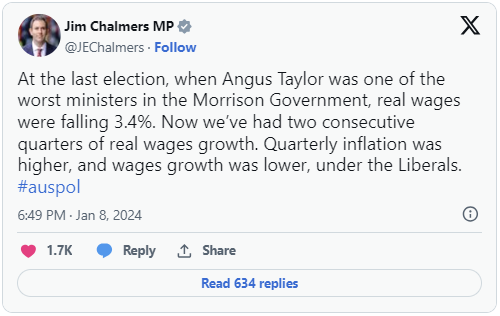

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has been pointing out that in the June quarter and the September quarter (the three months to June and to September) real wages grew for the first time in years. By that he means that the wages index compiled by the Bureau of Statistics began growing faster than the consumer price index.

It’s better than growing more slowly, but it tells us next to nothing about what’s happening to buying power. Here’s why.

Why CPI understates today’s living costs

Way back in the late 1990s, more than a quarter of a century ago, the consumer price index (CPI) used to actually reflect the cost of living. It included all of the big costs incurred by households, including – importantly – mortgage interest payments. At the time, mortgages accounted for an average of $5 of every $100 each wage earner spent.

Then in September 1998, in response to representations from the Reserve Bank and the Treasury, the bureau changed the way it calculated the index. It excluded mortgage and other interest payments, in a decision it acknowledged would make the index worse at measuring living costs.

It still carries the warning on its website, saying the consumer price index is

not the conceptually ideal measure for assessing the changes in the purchasing power of the disposable incomes of households.

The index actually does a pretty good job of measuring changes in living costs at times when mortgage rates aren’t much changing. But at times when they are tumbling, it’ll overestimate living costs. And when mortgage rates are soaring – as they have been lately – it will way understate what’s happening to living costs.

We know by how much. For years, the bureau has also published a separate set of measures it pointedly calls “living cost indexes”. These do include mortgage and other interest charges, and for households headed by employees (for whom the buying power of wages matters), they are substantial.

Living costs are up 9%

While the consumer price index (the one quoted by the treasurer) increased 4.1% for the year to December, the latest living cost index for households headed by wage earners climbed 9%.

For these working households, the price of food climbed 4.8% in the year to September, the price of electricity 14.5% and the price of mortgage interest charges 68%.

It’s the increases in mortgage rates that have made the increases in the other prices hurt so much.

The overall increase in prices faced by wage-earners – 9% – is way above the typical wage increase of 4%.

Bill Mitchell of the University of Newcastle points out that on this measure, the correct one, the buying power of wages has been falling for two and a half years. He says it puts the treasurer’s comments in a wholly different light.

Why we should distrust the CPI

Working Australians are right to distrust the consumer price index, which is something the Australian Council of Social Service warned the bureau about when it made the change.

Each month, the Melbourne Institute asks Australians whether their family finances have deteriorated over the previous year. Usually, about one-third of those surveyed say they have.

But for more than a year now, around 50% of those surveyed have been saying their finances have got worse. That’s a peak not seen since the global financial crisis, and one that has lasted longer.

Asked about family finances over the next 12 months, more than 30% say they’ll worsen further. It’s usually 20%.

Looked at from today’s perspective, the arguments put forward in 1997 for weakening the consumer price index as a measure of living costs are unimpressive.

Back then, the Treasury noted that many welfare recipients didn’t have mortgages and that a consumer price index that excluded them would better reflect their living costs.

The Reserve Bank argued interest rates were “conceptually different from other prices”. In any event, it wanted them excluded because it found it hard to use higher interest rates to bring down inflation if those higher rates pushed the measure of inflation up.

The change attracted little attention at the time, because mortgage rates weren’t moving much. By the time they did, the change had been bedded down.

But here’s some good news

For most of the time since the change, mortgage rates have either increased gradually or been cut, meaning the difference between what the consumer price index has been telling us and what’s been happening to us hasn’t been too stark. It’s been stark lately because interest rates have been rising quickly.

The good news – and there is good news – is that financial markets expect rates to begin falling this year, with the next move down.

Inflation as measured by the consumer price index (inflation excluding mortgage rates) is already falling.

It makes now a particularly good time to announce measures to address the cost-of-living crisis. We need them because we really are in something of a crisis. Things are a lot worse than the official index suggests.

And there’s a chance that soon they’ll begin to get better, allowing the prime minister to claim a win.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.