Investing can often feel like one giant prediction game. Most financial market commentary involves forecasts about the future that are hastily discarded and wilfully forgotten, and many investment approaches are founded on taking bets about the complex interactions of economies and asset prices. The problem with all this activity is that the world is a highly uncertain place and we are wildly overconfident in our ability to foresee what will happen next. A fact confirmed (again) in a recent study by Jeffrey A. Friedman, an associate Professor of Government at Dartmouth College.

Friedman ran a large-scale study of over 63,000 judgements made by nearly 2,000 national security officials from NATO allies and partners. The expert participants were given a set of 30 to 40 statements and had to estimate the chances that they were true.

Such as:

“In your opinion, what are the chances that NATO’s members spend more money on defense than the rest of the world combined?”

Or apply probabilities to future events:

“In your opinion, what are the chances that Russia and Ukraine will officially declare a ceasefire by the end of 2022?”

How did these experts fare when posed these questions?

It is fair to say that their calibration was a little off or, to put it another way, they exhibited pronounced levels of overconfidence.

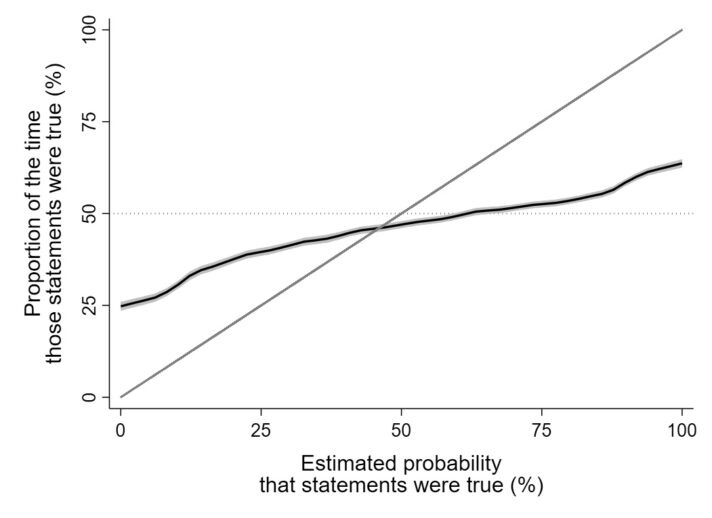

When the officials believed that a statement was likely to be 90% true, this was the case on only 57% of occasions. On the flip side, when a statement was assigned a 10% likelihood of truthfulness, it was correct 32% of the time. Notably, participants were more likely to say something was true when it was not, than the reverse (false positives were more common).

There was also a problem in dealing with certainty. When a participant had absolute confidence that a statement was false, they were incorrect 25% of the time. (They were obviously ignorant of Cromwell’s rule).

Here is a visual depiction of the calibration gap, or level of overconfidence:

Friedman’s paper goes in to more detail on the study, and he has also written an excellent book on decision making under uncertainty, which I would strongly recommend, but I wanted to turn to the implications of this study for investors:

Be very careful with geopolitical risks: Investors get very excited about geopolitical risk and love the opportunity to become foreign policy experts for the week, but making decisions based on geopolitics should be avoided. In Friedman’s study, experts in the field consistently made off the mark, poorly calibrated judgements – what chance do generalist investors have?

Financial markets are harder to predict than most things: Although the foreign policy questions in Friedman’s study were difficult, they are not as challenging as those many investors try to tackle. When investors make market predictions, they are attempting to forecast something as complex and chaotic as the global economy and how that will impact financial markets. It is incredible to me that anyone thinks this is possible.

Reduce your confidence levels: The participants in the study were overconfident, investors are overconfident, humans are overconfident. A very useful rule of thumb is to reduce our conviction every single time we express a view, this will almost certainly make our guesses more realistic.

Don’t make an investment approach reliant on predictions: I appreciate that it feels like we should be constantly making predictions about financial markets – it is interesting, lucrative and everyone else is doing it – but it is a really bad idea.

Make easier predictions: Of course, all investing involves making predictions about the future in some form but let’s make easy ones. I predict that over the next decade economies will grow, and stock markets will generate real returns. It is a forecast, and it is not certain to be true, but I have a reasonable level of confidence in it being so. Simple predictions, humbly made are always the way to go.

Reduce overconfidence by diversifying: Diversification is an exercise in humility. The future is uncertain, and we are terrible at making predictions, so our portfolios should reflect this.

If you are reading this and thinking that financial market forecasts are not really as difficult as I am making out then feel free to replicate Friedman’s test. Make a set of statements about the future and apply a probability to them being true. Things like these:

The ten-year US treasury yield will be above 5% by the end of 2026.

Or

The US equity market will not lose more than 25% in value at any point over the next 12 months.

Let me know how you get on.

It is an oddity that investors are often reluctant to systematically measure themselves in this way given how much time we spend making predictions. It suggests that even though we behave in an overconfident way underneath it all we know the truth, we would just rather not remind ourselves of it.

Note: All opinions are my own, not that of my employer or anybody else. I am often wrong, and my future self will disagree with my present self at some point.

Joe Wiggins is Director of Research at UK wealth manager, St James’s Place and publisher of investment insights through a behavioural science lens at www.behaviouralinvestment.com. His book The Intelligent Fund Investor explores the beliefs and behaviours that lead investors astray, and shows how we can make better decisions.

This article was originally published on Joe’s website, Behavioural Investment, and is reproduced with permission.