In today’s investment landscape, the dominance of the US—especially a handful of mega-cap technology companies—is hard to ignore. These firms have powered a disproportionate share of global equity market returns in recent years, and the US now accounts for around 75% of the MSCI World Index. The so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ have captured investor imagination and capital alike. But when nearly everyone is crowded around the same trade, it’s worth asking: what if we’re all looking behind the wrong door?

Enter the Monty Hall problem. This classic probability puzzle, loosely based on a 1970s game show, involves a contestant picking one of three doors—behind one is a car, behind the others, goats. After the contestant picks, the host (who knows what’s behind each door) opens one of the remaining doors to reveal a goat. The contestant is then given the option to switch. While most stick with their initial choice, switching actually doubles the contestant’s odds of winning the car!

The puzzle is a compelling metaphor for today’s markets: just because something feels obvious—or has worked recently—that doesn’t make it the right choice in future.

Lesson 1: The obvious choice isn’t always the best one

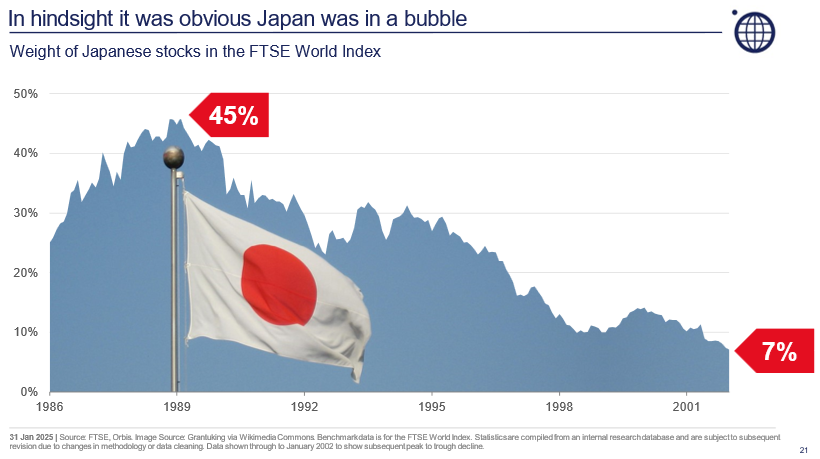

On the surface, staying heavily invested in US equities looks sensible. It’s the world’s largest economy, home to dominant companies, and it has outperformed for over a decade. But history reminds us that market leadership shifts. In the late 1980s, Japan made up more than 40% of the global index—before its bubble burst. Similarly, the dot-com crash of 2000 exposed the perils of speculative excess in the technology, media and telecoms sectors. Both events were obvious in hindsight, but herd mentality and a fear of missing out clouded judgements at the time.

Today’s US equity market shows signs of similar concentration and froth. President Trump’s renewed tariff threats have unsettled markets as well as global supply chains, and fresh US export restrictions on chips to China prompted warnings from NVIDIA about billions in lost revenue. Meanwhile, valuations remain stretched.

For a generation of investors raised on uninterrupted American outperformance, it may be time to reassess where the real risks—and opportunities—now lie.

Lesson 2: Insight matters—but only if you act on it

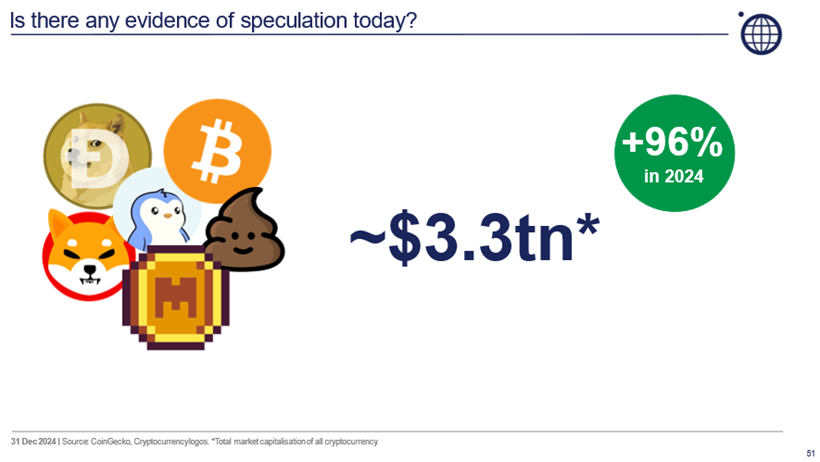

Spotting market dislocations is one thing, acting on them is another. Investors may sense that sentiment is frothy but going against the crowd is always difficult. It’s particularly hard when the prevailing narrative is that “AI is the tide that will lift all boats” and investors are surrounded by highly speculative activity being wildly profitable.

At the end of 2024, cryptocurrencies and digital tokens were valued at $3.3 trillion—up 96% in a year. In a sign of the times, ‘Fartcoin’ which was launched in October ended 2024 with a market cap just shy of $1 billion. That’s more than three times the peak valuation of Pets.com, the dot-com bubble’s poster child, which managed to go public and go bankrupt in the same year back in 2000.

Meanwhile, US hyperscalers have been ramping up capital expenditures to chase AI dreams—with no clear line of sight to monetisation. Their ratios of capex to sales are rising sharply, and it’s not clear that returns will justify the outlays.

And that’s the crux of it: markets aren’t always efficient—especially when investors are chasing hype over substance. As the Monty Hall problem teaches us, knowing the odds isn’t enough. You need to tune out the noise and have the conviction to switch, even when it feels uncomfortable.

Lesson 3: Nothing is certain—apart from death and taxes

Even with the optimal Monty Hall strategy, contestants only win two-thirds of the time. In investing, research shows that even top-tier managers only get it right about 60% of the time. That’s why broad and thoughtful diversification—across sectors, geographies, and styles—is so valuable.

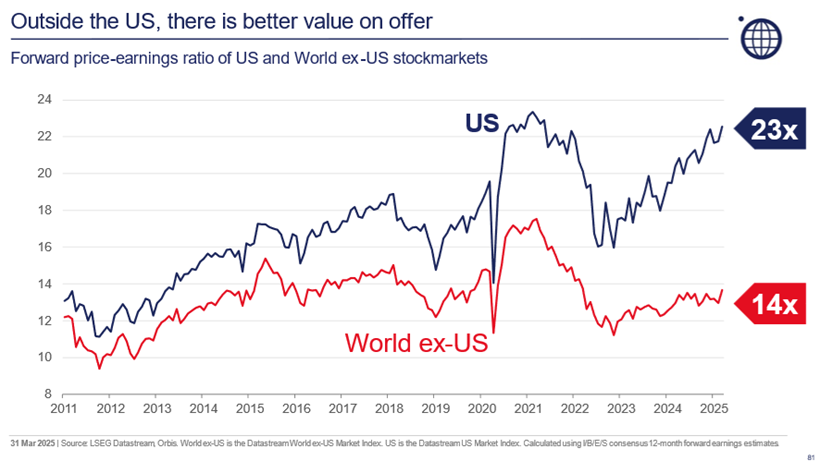

Many investors today believe they’re diversified because they hold global index trackers. But with US stocks now making up nearly 75% of global benchmarks like the MSCI World Index, many portfolios are far more concentrated than they appear. That concentration is made more problematic by valuation levels. The S&P 500 trades at around 23 times forward earnings—well above its historical average and significantly more expensive than global markets, which average closer to 14 times. This discrepancy suggests that investors might be paying too much for the comfort of familiarity.

Meaningful diversification is about holding assets that behave differently—and the benefits are felt most when the prevailing market trends reverse. Investors need to ask whether their portfolios are truly positioned to weather regime changes. And if they aren’t, what’s stopping them from switching?

Reframing comfort zones

The Monty Hall problem teaches us that the obvious answer isn’t always the correct one. The same holds true in investing. Sticking with the US and big tech may have felt safe, until very recently at least, but sticking with what’s familiar can offer false comfort. In today’s environment, defined as it is by extreme market concentration and investor herding, the real edge lies in having the conviction to take a different path.

Ultimately, investors must always be sceptical about simply following the prevailing market consensus, as current prices already reflect those views. Proper diversification today also requires going beyond simply mirroring global benchmarks.

Just as switching doors improves your chances in the Monty Hall problem, being willing to look beyond the obvious and focus on where value is being overlooked is the key to long-term success in investing.

Werner (Vern) du Preez is an Investment Specialist at Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information at a point in time and not personal financial or investment advice. It should not be used as a guide to invest or trade and does not take into account the specific investment objectives or financial situation of any particular person. The Orbis Funds may take a different view depending on facts and circumstances.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.