One of the foundational beliefs that drives strategic asset allocation is the existence of the equity risk premium (ERP) – that is, that by taking on greater risk of owning equity an investor will be rewarded with greater return.

Based on research undertaken by Jeremy Siegel[1] in the early 1990s “The Equity Premium: Stock and Bond Returns since 1802”, (and expanded by others in following years), very long run data on stock and bond returns was compiled which purported to show that stocks outperform bonds over the long run.

Combined with other research like the annual Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns publication, which many have utilised over the years, the existence of an ERP of 3-4% per annum (an 8% equity return versus a 4% bond return) has become embedded in investment return assumptions.

These assumptions drive the high allocation to equities typically present in diversified investment portfolios. Yet recent updated research suggests that the existence of the equity risk premium may be more episodic than these assumptions imply.

A paper published almost a year ago in the Financial Analysts Journal[2], “Stocks for the Long Run? Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No”, by Edward F. McQuarrie, questions this fundamental assumption. The paper extended the historical analysis back further to 1792 and, importantly, updated it to:

- Include securities trading outside New York (in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and southern and western US cities), increasing the coverage to 3-5 times more stocks and 5-10 times more bonds;

- To capture more failures, reducing survivorship bias;

- Include federal, municipal and corporate bonds; and

- Calculate a cap-weighted total return for stocks.

While historical data must be treated with a significant caution, especially over such long periods, these enhancements appear to be a large improvement on the original data. For more detail see the paper, which details the methods and contains links to the files containing raw data, for use by future researchers.

Shortcomings remain, such as annual frequency of data, time-averaged data and exclusion of stocks that traded over the counter. Yet the impact of these enhancements are significant. Stock returns before 1871 are much weaker due to the reduction in survivorship bias, while bond returns look more positive due to the broader collection of securities.

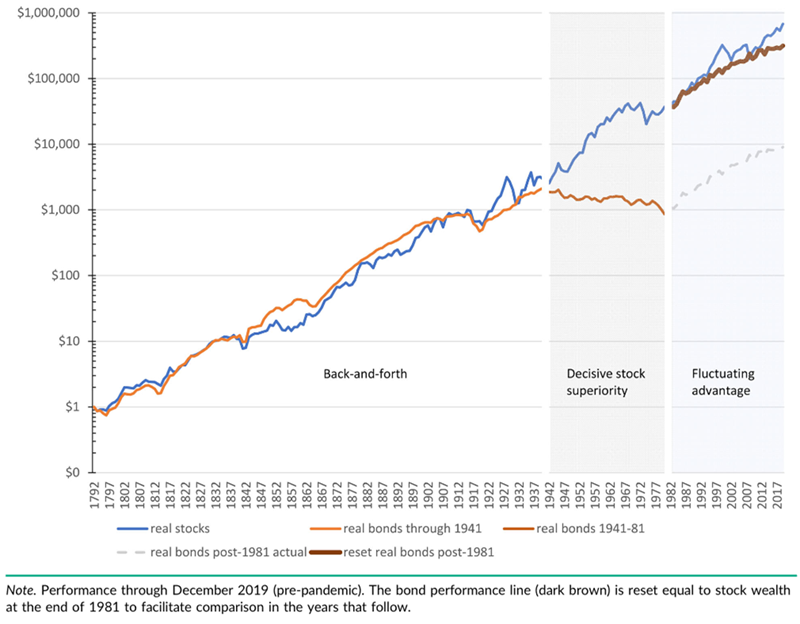

The chart below from the paper shows the new record since 1792, and is quite striking. Two recent periods are highlighted (stock outperformance post World War 2 to 1980, and the period since 1980 to now), with the bond performance line also reset at the beginning of 1980 to facilitate comparison.

Stock and Bond Performance Since 1792

(including bonds rebased to 1981)

The revised record suggests that the strong period of equities outperforming bonds was mostly in the post-WW2 period up until 1980. Since 1980, stocks and bonds have performed about the same: while stocks have had periods of outperformance (tech boom up to 2000, pre-GFC, and the current AI rally), they have been followed by reversals. Meanwhile the decline in inflation and bond yields meant that bonds have kept up with equities since 1980.

Over the very long run, the data suggests that the ERP did not exist in the 150 years before World War 2 (WW2) and the 40 years since 1981. It was only the period from post WW2 to 1980 that the ERP was clearly evident. The implication is that rather than being a long-run phenomena, the ERP may have been a 'short-term' event triggered post WW2 until the early 1980s, which has then been baked into historical returns that have been used to 'prove' its existence ever since.

Clearly the existence, or not, of an ERP has significant implications for portfolio construction. To just note two: if the ERP is in fact much lower than normally assumed, there is less need for portfolios to load up on equities to generate returns. It also impacts the total expected return for a portfolio, which has implications for retirement planning.

Unsurprisingly, the paper has generated a lively debate among leading US finance academics. For those interested in further discussion of this topic, the CFA Institute Research Foundation will shortly publish some of this commentary, which will undoubtedly be insightful and interesting!

Phil Graham is an independent director and consultant, and a former Chief Investment Officer. He currently serves as a Trustee on the CFA Institute’s Research Foundation.

[1] Siegel, J.J. (1992); “The Equity Premium: Stock and Bond Returns since 1802”, Financial Analysts Journal, Volume 48, Issue 1, (1).

[2] McQuarrie, Edward F. (2023); “Stocks for the Long Run? Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No”, Financial Analysts Journal, Volume 80, Issue 1.