The Herengracht Canal in Amsterdam has been a favoured strip of real estate in the city since the 1620s. The Herengracht House Index, constructed by finance professor Piet Eichholz of Maastricht University, tracks house prices in the area over a 380 year period – commencing with the Dutch ‘Golden Age’. Over that time, real (i.e. inflation adjusted) house prices have only doubled, which corresponds to an annual average price increase of something like 0.1%. This would indicate that despite short-term rises and falls, prices roughly follow inflation.

Valuing like other financial assets

What could this mean for investors in the Australian residential property market? It may have looked like an attractive option recently. Auction clearance rates have been healthy, but rising prices have prompted media commentary on a possible housing ‘bubble’. What do we find if we apply value-investing principles?

We’ll start by assuming that residential property, at least the investment kind, derives its value in the same way as other financial assets - by producing cash flows - and obeys the same fundamental financial laws.

Since property income is fairly predictable, the valuation exercise should be straightforward. We just need three numbers:

- discount rate, or rate of return required by an investor

- net rental income generated

- long-term rental growth rate

We can plug these values into a simple formula that will calculate the present value of the cashflows into perpetuity, following the same principles used to value a business.

A discount rate reflects the rate of return an investor needs to compensate them for the risk of investing in a particular asset. A good way to estimate it might be to start with the 10-year government bond rate (a proxy for the rate that applies when there is no risk, currently around 4% p.a.), and add a risk premium.

In the case of equities, the risk premium is commonly thought to be around 5-6%. I think a case can be made for a lower risk premium for property, given that it has a more stable profile, but we should also consider that property is a much less liquid asset than equities, and investors should demand some compensation for this. For the sake of argument, let’s choose a risk premium of 4%. This gives us a required rate of return of around 8%.

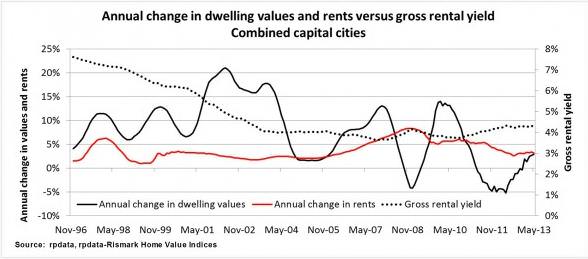

Net rental yield is the next piece of information we need. The chart below, published by RP Data, shows a current gross rental yield for Australian capital cities of around 4.3% p.a.

To calculate a net rental yield, subtract all the expenses that an investor must incur in generating the gross rent, including property management fees, maintenance, insurance etc. A reasonable estimate may be around 1.0%, which gets us to a net rental yield of 4.3% - 1.0% = 3.3%.

The final number required is the long term growth rate in rents. As shown in the chart above, a figure just above 3% p.a. may be a reasonable estimate. Let’s assume 3.2%.

Combining these numbers into a valuation can be done as follows: divide the annual rent earned on a property by a divisor, which is calculated by subtracting the long term growth rate from the discount rate, as set out below.

Value = Net Rent p.a. /(Discount Rate – Growth Rate)

This is the formula for calculating the present value of a stream of cash flow that grows at a fixed rate in perpetuity. If a property generates $20,000 per year of net rent, we would calculate its value as $20,000/(8% - 3.2%) or $20,000/4.8%, equal to around $416,667.

If that property can be bought today at a net yield of 3.3%, it would imply that the market price of the property today is $20,000/3.3% = $606,061. This is significantly higher than our valuation of $416,667. On the basis of the discount rate and long term growth rate we assumed, buying property on a net rental yield of 3.3% appears hard to justify.

Continuing assumption of capital growth

Over the past three decades, there has been a fourfold increase in Australia’s indebtedness as a percentage of annual disposable income, to 150%, as well as massive growth in property prices. Together with the above analysis, these facts indicate that the same level of growth is not sustainable. If this is correct, it may pay to be cautious about buying on the basis of a continuation of assumed capital growth.

Of course, the conclusions you reach with this approach depend on the assumptions you put into it, and the purpose here is not to argue that property is overpriced. Rather, it is to set out a framework that allows some basic assumptions to be converted into a fundamental value. By doing this, you can decide for yourself whether there is long term value to be gained.

Roger Montgomery is the Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund, and author of the bestseller, ‘Value.able'.