One event that grabbed headlines around the world in late January 2017 was the Dow Jones Industrial Average finally hitting 20,000 for the first time. The ‘Dow’ is the world’s oldest and most widely-followed stock market index but it is also deeply flawed. It only tracks 30 stocks and they are not the largest stocks in the US by any means. The weighting of stocks is almost arbitrary and is based on the nominal share price of each stock and not on their relative revenues, profits, market values or importance. Despite the flaws, it is symbolic and it provides a reasonable proxy for US stocks in general. All other indexes of the US stock market have hit all-time highs recently, so the US market is hot.

Why the Dow is misleading

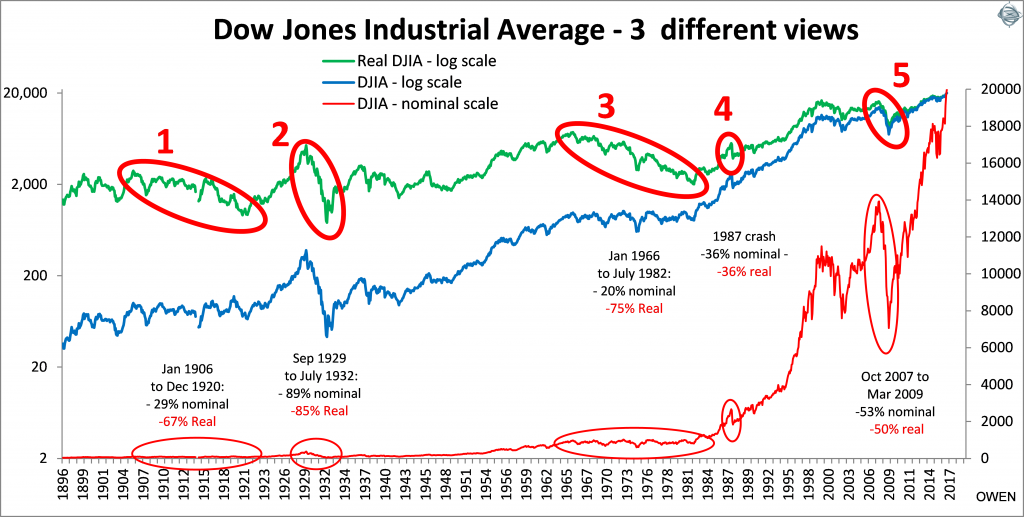

A nominal index like the Dow hides many sins. The red line on the chart below was widely published last week. It shows the Dow virtually flat for 80 years and then the red line surges in the 1990s ‘dot-com’ boom, then again in the 2003-07 credit boom, crash in the 2008-09 sub-prime crisis, and finally make the rapid, steep ascent to the summit since 2009.

Click to enlarge

This traditional view is grossly misleading as it makes the recent cycles appear much more dramatic than earlier cycles due to the nominal scale used in traditional charts (right scale).

We need to add two more lines to see what is really going on. The first is the blue line which is the same nominal index but on a more sensible scale, a ‘log’ scale (or ratio scale) on the left side. This type of scale shows the cycles in the same light. For example, a doubling or halving of the index appears as the same size change regardless of the level of the index at the time.

The blue line shows that the 1929-32 crash (‘2’ on the chart) was much more serious than the 2008-09 sub-prime crash. The index fell -89% in 1929-32, much worse than the -53% fall in 2008-09, but it is almost invisible on the traditional nominal scale chart (red line in lower left).

We also need to add a third line to adjust for inflation (green line, which also uses the left log scale). What matters to investors is the real spending power of their wealth after inflation, and this picture not nearly as rosy. We see that the ‘real’ index after inflation has only gone from 2,000 to 20,000 in 120 years – that’s less than 2% real growth per year on average, which is hardly inspiring. True that doesn’t include dividends, but most investors live off the dividends and rely on the capital value increasing in real terms so that dividends can also keep ahead of inflation.

This inflation-adjusted picture also reveals two more bear markets: ‘1’ was the long bear market from 1906 to 1920 when share prices fell 67% in real terms, and ‘3’ was 1966 to 1982 when the prices fell 75% in real terms. Both of these bear markets lasted an agonising 15 years, much longer than the other crashes, and much worse after inflation than the sub-prime crash, the dot-com crash, and the 1987 crash. Inflation cripples returns and lifestyles for many years at a time.

Australian shares are a long way off their highs

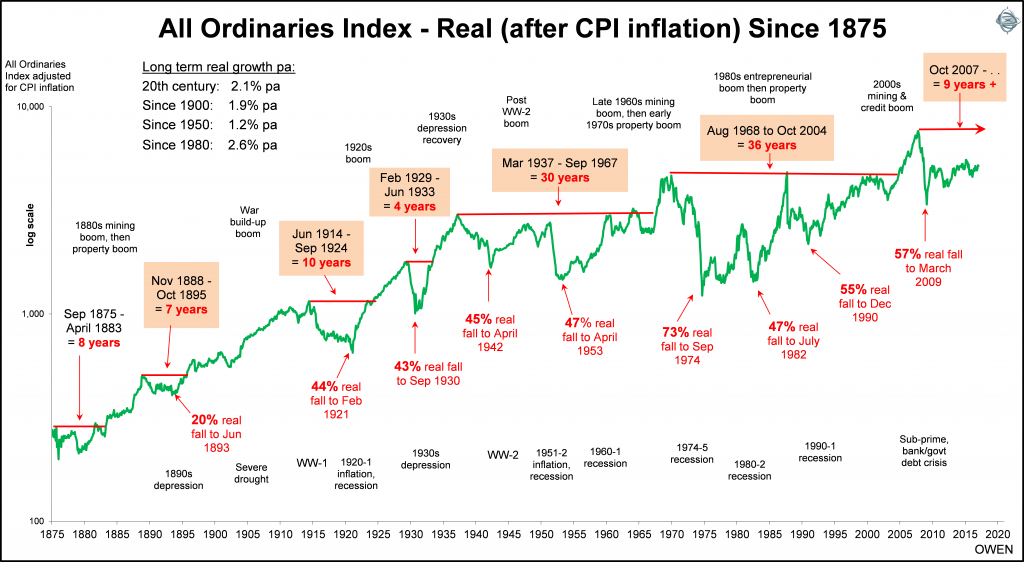

Here is the same chart for Australian shares, using the All Ordinaries index and its predecessors, adjusted for Australian inflation. Using only the real (after inflation) line shows the cycles more clearly. The long picture is similar to the US, with the price index growing by just 2% per year in real (after inflation) terms.

Click to enlarge

The sub-prime crash in 2008-09 was not unusual in the scheme of things. Contrary to the media hype at the time, it wasn’t a ‘once in a century’ event or even ‘once in a lifetime’ event, we have had several declines of similar or worse magnitude, one every decade or so.

Our ‘big one’ was the crash from 1968-74 because we had a much bigger speculative mining bubble in the late 1960s and then a huge debt-fuelled property construction boom in the early 1970s. The All Ordinaries index took 36 years to recover its real value. That’s a long time to wait before seeing any real growth!

Inflation adjustment changes the story

The All Ordinaries index at 5,675 (at time of writing) is just 5% higher (after inflation) than it was at the top of the mining boom on 6 January 1970. Most people who were lured into the speculative mining stocks of the day lost the lot. But what about those who avoided the speculative stocks and thought they were staying safe by buying big blue chip stocks? The so-called blue chips are barely breaking even (after inflation) even today after nearly 50 years!

The big stocks that dominated the index back then are the same companies today. Bank of NSW (now Westpac) is just ahead of its 1968 peak price, but ANZ and NAB are still behind. BHP and Woodside are just above water but CRA (now Rio) and Santos are still well behind. CSR, QBE and Lend Lease are all below their 1960s peaks.

Sure they have paid dividends along the way, but unless we want to keep working all of our lives, the aim is to live off the dividends and see the share price (and dividends) grow ahead of inflation. Timing is everything. If we follow the crowd and the media hype and buy at the top of a boom we could be waiting many decades to get back to square one before we can see any real growth.

The main lesson from the Australian and US charts is that big crashes occur frequently and they can take decades to recover in real terms after inflation. It has now been nine years since the top of the last boom, and prices are still a long way from square one. The aim is to avoid panic buying in boom time frenzies, and avoid panic selling at the bottom when prospects look darkest.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at independent advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.