Franking credits are an emotive topic. Many people love them and pensioners often rely on them to supplement their retirement income. Arguably, they contributed to thwarting Bill Shorten’s bid to become Prime Minister in 2019.

Yet, at a broader level, there needs to be a serious discussion about whether franking credits are hurting business investment and the economy.

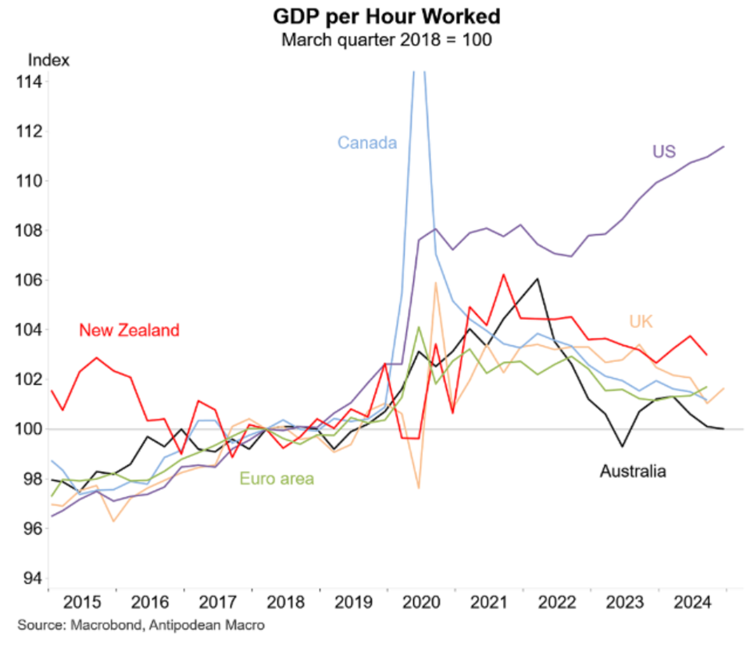

Investment and per capita GDP have languished over the past decade and the Labor Government has made it a priority to find out why. It’s ordered the Productivity Commission to conduct no less than five separate inquiries into the issue and is also hosting a productivity roundtable with economists in August.

Here, I’ll outline why franking credits should be part of the debate about our stalling economy.

To be clear, this article isn’t about whether franking credits, especially refunds, are fair or not. Instead, this is about the second, third, and fourth order effects they may be having on businesses, markets, and the economy.

What are franking credits?

There’s a lot of confusion about what franking credits are and how they were created, so let’s briefly clear this up.

Franking credits are tax paid by companies that are attributed to shareholders.

Before 1987, a company made a profit, paid tax, and paid dividends to shareholders, who then paid tax again.

In 1987, Treasurer Paul Keating created the dividend imputation scheme to do away with the government’s double taxation.

The Howard Government expanded the dividend imputation scheme in 2001 so taxpayers with excess imputation credits could get refunds from the ATO.

In the 2019 election campaign, Labor leader Bill Shorten proposed to abolish the refund system to ‘save’ $60 billion over the subsequent decade. The issue contributed to him losing the unlosable election.

How do franking credits work?

A franking credit – also known as an imputation credit - is a tax credit that can be attached to dividends paid to shareholders. Franking credits are designed to offset the income tax already paid by the company, and the intention is for the shareholder to pay their own individual rate of tax on the profits instead. The aim is to prevent double taxation or paying tax twice on the same income.

Here are two examples of how it works in practice:

Tim owns shares in CBA. The company pays him a fully franked dividend of $700. His dividend statement indicates there is a franking credit of $300. This represents the tax that CBA has already paid. It means the dividend, before company tax was deducted, would have been $1,000 ($700 + $300).

At tax time, Tim must declare the income of $1,000. If his marginal rate is 20%, he would have paid $200 in tax on the dividend. Because CBA has already paid $300 in tax, Tim will get a refund of the difference, totalling $100 ($300 - $200).

If Tim was in a higher tax bracket, he may not have been entitled to a tax refund.

And:

Genoveve holds shares in CSL. The company paid her a dividend of $750 and her statement showed a franking credit of $750, amounting to total income of $1,500.

Genoveve pays no tax. At tax time, she can claim back the $750 tax paid by CSL. In other words, she gets a tax refund of $750.

First-order effect: Higher dividend payout ratios

Government policies influence the behaviour and actions of individuals and companies, and the introduction of the dividend imputation system was no different.

Individual shareholders quickly came to revere franking credits. They demanded more dividends with franking credits attached. And companies obliged by paying out more of their earnings as dividends. The impact was immediate and dramatic.

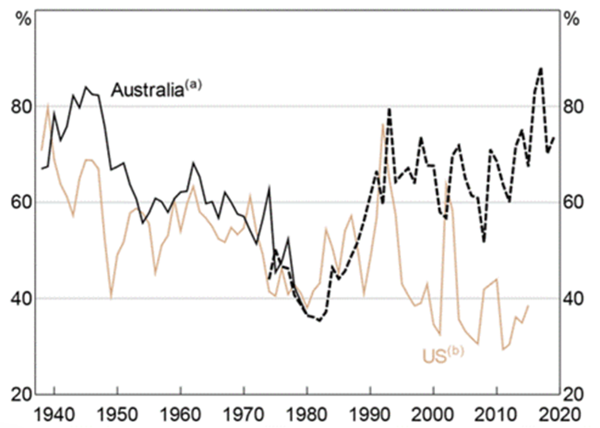

Dividend payout ratio

Source: RBA

Dividend payout ratios for ASX All Ordinaries companies went from mid-40% to 80% within a decade and have stayed high ever since.

Second-order effect: lower business investment

Higher dividend payout ratios mean companies retain less of their free cashflow for reinvestment into their businesses.

Say a company earns $20 million in a year, and pays 70% of profit as dividends, it results in 30% or $6.8 million being potentially reinvested back into the company.

If the dividend payout ratio was 50%, $10 million would be available for reinvestment, $3.2 million more than if the ratio was 70%.

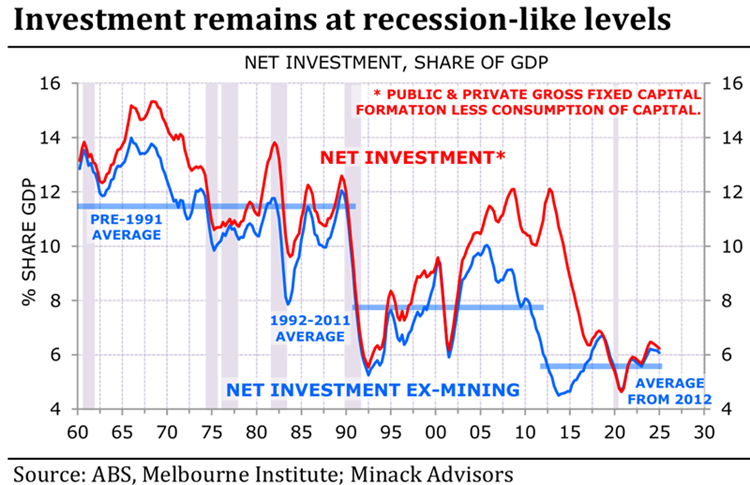

There’s little doubt that companies acquiescing to shareholder demands for higher dividend payouts has led to lower business reinvestment than there otherwise would have been. And that this has contributed, at least in part, to the major fall in business investment in Australia.

Yes, business investment has only really collapsed over the past 15 years. Before that, it was still reasonably healthy.

Keep in mind, though, that the circumstances back then were different. In the 1990s and 2000s, Australia benefited from the de-regulation policies of Hawke and Keating. There was also the rise of China and the dramatic impact that had on mining demand, which filtered through to other parts of the economy.

Consequently, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that franking credits have led to reduced listed company investment. And given the size of the listed companies, this has resulted in a broader slowdown in business investment over the past four decades.

Third-order effect: potentially lower ASX market returns

Prominent commentators like Roger Montgomery blame Australia’s dividend fetish for the ASX’s lacklustre performance since the GFC.

Here is Montgomery’s logic:

“Australian companies tend to pay out the franked dividends to make their super fund and retiree shareholders happier. Of course, shareholders would be better off if a company earning a high rate of return on equity kept the dividends and reinvested them. Even after discounted capital gains tax and franking credits are considered, the investor who insists their company retain profits at 20 per cent rates of return on equity will be far better off than if they take the dividend.”

He has a point. If a company has a return on equity (ROE) of 20%, and it retains 100% of the profit, then shareholder returns over the long term are likely to be close to 20% per annum. Fantastic.

The issue is that not all companies have ROEs that high. The ASX 300 has an average ROE of 12%. That means many companies have ROEs sub-10% and below their cost of capital, and when that happens, it’s arguably better for these businesses to pay out more dividends rather than less ie. their returns are too poor to warrant retaining much in the way of earnings.

Another possible argument in favour of higher dividend payouts is that dividends enforce discipline on companies. Australian companies have a long history of blowing large wads of cash on silly acquisitions. Witness James Hardie’s attempted takeover of late. In this respect, it’s understandable that shareholders may prefer dividends over reinvestment.

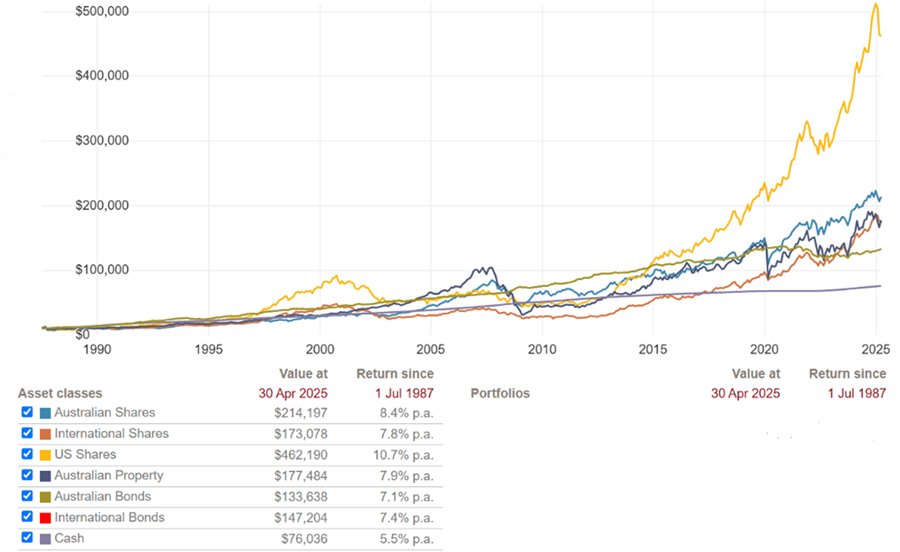

Getting back to Montgomery’s notion that the dividend fetish has dragged on market returns, the evidence isn’t so clear cut. Since franking credits were introduced in 1987, the ASX 300 has returned 8.4%, close to its longer run average, and well above international shares.

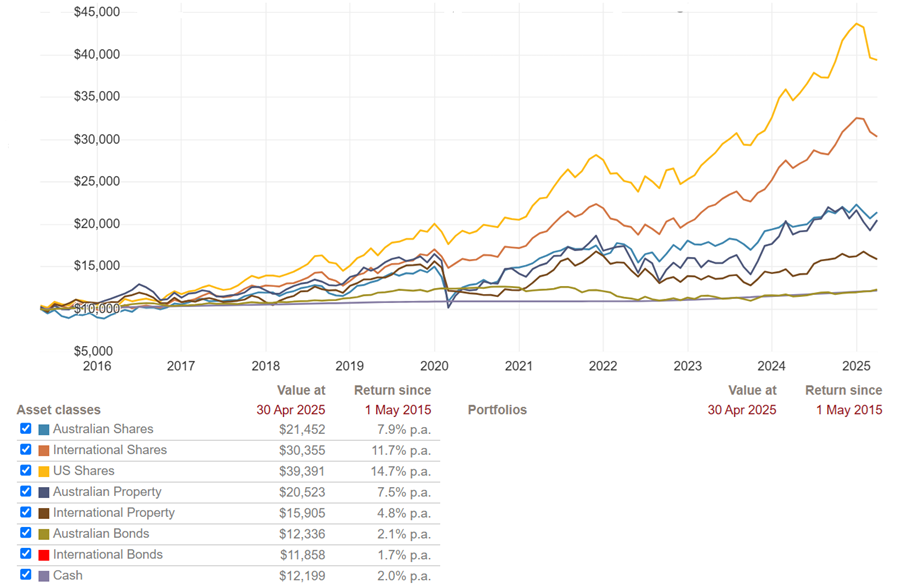

The past decade has been a different story, though it’s mainly been because of the stellar performance of the US, which now accounts for 64% of world equity indices.

Though I have sympathy for Montgomery’s argument, I think the evidence that higher dividends have reduced ASX returns is still inconclusive.

Fourth-order effect: lower productivity?

Have franking credits impacted productivity and the economy?

Despite what our economists believe, productivity is a difficult thing to measure. Put simply, productivity is how efficiently work is done. It depends on both the efficiency of workers and the quality of materials used by workers.

For instance, if better quality technology is used, it tends to improve productivity. Yet, if management of workers is poor, then better technology may not help a company’s productivity. In fact, better management with lower quality technology may be able to do more.

So, productivity relies on investment in better machinery, technology and tools, as well as quality management overseeing the work.

Governments also play a role in productivity. For example, they can provide modern roads for efficient transport. They can also provide open and transparent governance, as opposed to a corrupt regime, which can hold back productivity.

What do franking credits have to do with productivity? Well, if they result in lower business investment as I attest, then it does play a role in lower productivity potential.

But let’s overstate things: there are a lot of other factors that feed into productivity too.

What else influences productivity?

Competition, or the lack thereof, gets talked about a lot, and rightfully so. Australia is full of duopolies and oligopolies, from banks to supermarkets to electricity distributors to telecoms and supermarkets. These arrangements, backed by government regulation, reduce competition, and thereby lower investment, innovation and productivity.

CBA is the most expensive bank in the world by a distance and therefore the market believes it’s among the best banking franchises. Why then does Australia feel the need to retain its Big Four policy and prevent more competition in the sector?

While there might have been an argument once for this policy, surely the banks are big enough to handle themselves by now. And opening banking up to more competition is unlikely to lead to financial instability given the lead that the current banks have over any other rivals.

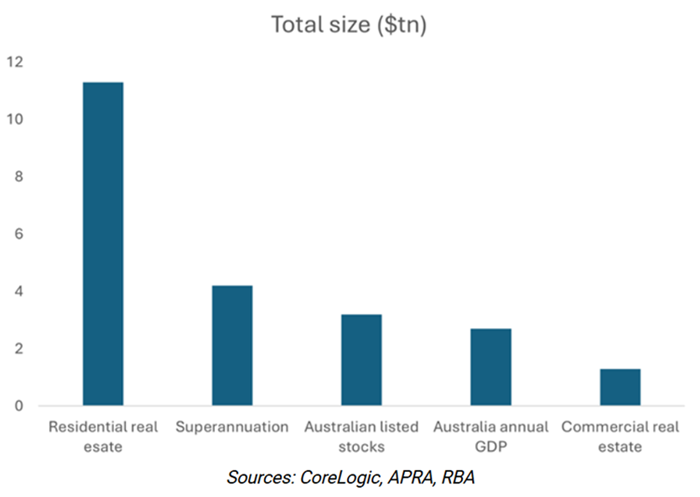

A less talked about factor in the productivity debate is over-investment in unproductive areas. I think Australia may be a world leader is this respect.

I show the following chart often because it encapsulates this over-investment in certain areas.

The size of the housing market – one of the least productive sectors – is four times that of annual GDP and dwarfs any other sector.

Is it any surprise that we have a productivity issue when so much money is directed, or ill-directed, towards residential property?

I’m not sure we can improve productivity and economic growth much without addressing housing.

There are a host of other factors which play a role in productivity, such as immigration, technology, entrepreneurship, and the list goes on.

Suffice to say that franking credits are part of the debate, though far from all of it.

Alternatives to dividend imputation

What kind of reforms do I propose for franking credits? I don’t have any set ones because any changes would have knock-on effects that would have to be dealt with through other reform.

It should be noted that there are lots of other models out there when it comes to taxing dividends as we’re one of the few countries – New Zealand and Malta are others – that have a dividend imputation system.

Canada grosses up dividend income and then offers federal and state tax credits to prevent double taxation. In many European countries like the UK, dividends are taxed as personal income, though at reduced rates. The US has double taxation though capital gains are taxed at a concessional rate. It discourages dividend payments and hence why companies prefer to buy back shares in America. In Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Brazil, dividends are not taxed as personal income.

In sum, I think franking credits are part of the productivity puzzle and should at least be studied along with other areas that may be holding our economy back.

The need to get economic growth moving again is urgent and everything should be on the table.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.