If you don’t know who you are, this is an expensive place to find out.

– Adam Smith, The Money Game

The Money Game remains one of my favourite all-time investment books. Both funny and wise, it was published during the first great tech boom, in 1967.

This was a few years before Buffett decided to close his early partnerships due to a lack of value opportunities. Instead, he decided to focus on fixing a woeful investment he had made a few years earlier called Berkshire Hathaway.

The Vietnam War was in full swing. The civil rights movement was upending post-war America, culminating in the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968. They were ‘unprecedented times’, yet the market ripped higher, peaking in December 1968.

During the 1960s boom, middle-class America became investors for the first time via an explosion of mutual funds (a bit like ETFs now), which made investing in the stock market easier. Portfolio managers (called gunslingers) became rock stars.

Everyone got rich from the boom. The relatively modest performance of the Dow Jones Industrials belied the rampant speculation that went on beneath the surface. Then, just as the masses piled in, came the 1970s…

A decade of going nowhere

Even Berkshire Hathaway struggled. After Buffett closed his partnerships in early 1970, partners had the option of buying into Berkshire at around $40 per share or seeking alternative investments.

By 1975, Berkshire was back around $40, after rising to nearly $100. Some of his early investors sold in a panic at the lows.

It was a tough time. New York City was bankrupt. Inflation was rampant and crime was rife.

All this is to remind you that what comes next is usually different to what came before.

The future is uncertain. We don’t know what tomorrow brings. And if you don’t know who you are (and what you’re doing, I might add), the stock market is an expensive place to find out.

Sometimes the market reflects this inherent uncertainty, like during the tough times of the 1970s, or after the GFC. And sometimes it doesn’t, like the late 60s, 1999/2000, and now.

Recently, the S&P 500 cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio (CAPE) moved above 40. It’s the first time it’s breached this level since 1999 and only the second time in history to do so.

While we only have one data point, in the 10 years following the S&P 500 peak in March 2000, the index lost on average 2.65% per year. Throw in annual average dividends of around 1.75% and the index still went backwards.

Add in inflation, and in real terms, passive investors suffered even more.

This is why I have concerns for the long-term, buy-and-hold passive investor, just as the strategy reaches peak popularity.

The iron law of the market is that whatever has been successful in the past tends to become popular. And whatever is popular tends to perform poorly in the future.

As to why, it all boils down to price

Think of it like a seesaw. When prices are low, history tells you future potential returns are high. But when prices are high (like now), future potential returns are low.

The higher those prices become in the short term, relative to long-term earnings trends, the poorer future returns will be.

With the CAPE ratio above 40, passive index investors (in the US) are looking at long-term future returns that are very likely to be negative.

In fact, based on the ‘what’s popular no longer works’ theory, I think passive investors everywhere are likely to experience poor long-term performance.

Not all ETFs are passive funds, I know. But investors think of ETFs as diversified and ‘easy’, and that they will continue to deliver.

Given the strong performance of most global indices, and the poor performance and high relative fees of many index-hugging ‘active’ fund managers, ETFs are now wildly popular.

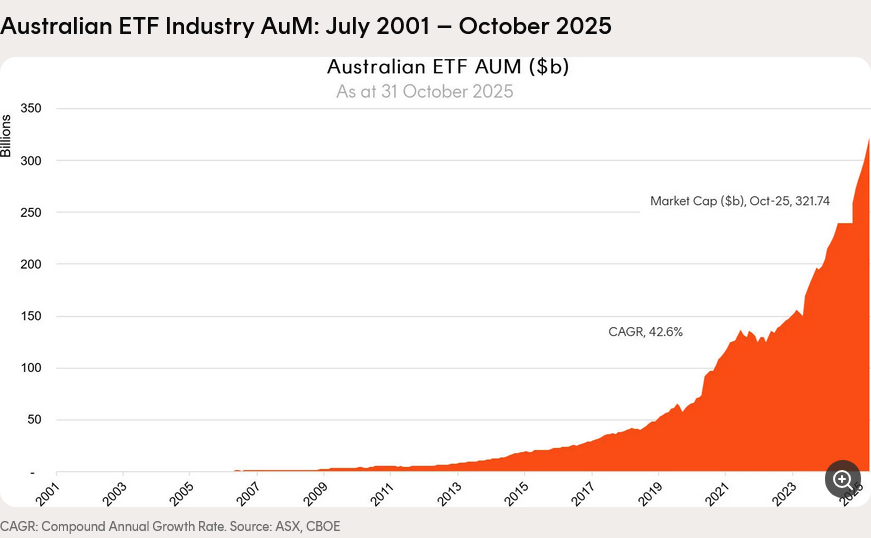

The latest Betashares Australian ETF Review for October, published on the 13 November, showed a record month of inflows at $5.99 billion. The Australian ETF industry reached a new record high of $321.7 billion in funds under management– a 4% monthly increase. Over the last 12 months the Australian ETF industry grew by 38.4%, or $89.2 billion.

You can see the popularity of the sector in the chart below. It looks like the NASDAQ in 1999!

Source: Betashares.

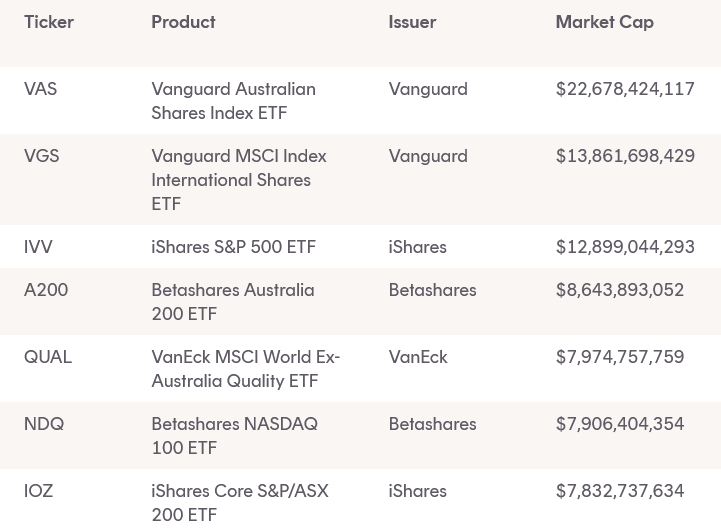

Six of the top seven ETFs in Australia by market cap are all index ETFs (see below).

Source: Betashares.

To be clear, I think low-cost index ETFs are excellent investment options for people who don’t have the inclination to watch their investments closely or the skill to make the right investments.

Dollar-cost averaging through the cycle is the best way to invest, rather than rushing in during the height of popularity, as many seem to be doing now.

In what is perhaps an ominous sign, Betashares launched a new ETF in September called the Betashares Wealth Builder Global Shares Geared (30-40% LVR) Complex ETF.

That’s just what investors need at this stage of the bull market!

Sometime in the future, after a few years of poor performance, many people are going to think, ‘maybe these passive ETFs aren’t what I thought they’d be. Nobody told me they might go nowhere for years.’

Some might even panic and sell out at the lows.

Towards the end of The Money Game, the narrator talks to his friend, known only as ‘The Gnome of Zurich’.

“One day in Spring, or maybe not in Spring, it will either be raining or it won’t”, said the Gnome of Zurich. “The market will be hubbling and bubbling, there will be peace overtures in the air, housing starts will be up, and all the customers’ men will be watching the tape and dialing their customers as fast as they can. On Wednesday the market will run out of steam, and on Thursday it will weaken. Profit-taking, profit-taking, the savants will say. Do not listen. Call me.”

Whether we are at a ‘call me’ time in the market right now, nobody knows. I certainly don’t.

But I do know that when themes/stocks/sectors are excessively popular, they become expensive and then perform poorly for years.

Investors ploughing into ETFs thinking it’s a cheap and easy way to invest will learn this lesson in the years ahead.

If they are genuine long-term investors with a disciplined dollar-cost average strategy, this won’t be a problem.

But if they are simply chasing performance and following the herd…well…as Adam Smith said, ‘if you don’t know who you are, this is an expensive place to find out.’

Greg Canavan is the editorial director of Fat Tail Investment Research and Editor of its flagship investment letter, Fat Tail Investment Advisory. This information is general in nature and has not taken into account your personal circumstances. Please seek independent financial advice regarding your own situation, or if in doubt about the suitability of an investment.