In the 1995 award winning film The Usual Suspects, the mythical figure Keyser Söze terrifies his enemies not through direct action but through reputation. He is more legend than reality, a spectre whose menace exists mostly in the imagination. Australia’s corporate tax rate occupies a strangely similar role. The headline figure of 30% is invoked in political debate as though it were a dead weight dragging on growth and driving companies offshore. But like Söze, the tax’s reputation looms much larger than its actual substance.

The reality is that Australia’s corporate tax system is unlike almost any other in the world thanks to dividend imputation. Introduced by the Hawke government in the late 1980s, this system abolished the double taxation of profits by attaching franking credits to dividends. Shareholders can use these credits to offset their personal tax obligations or receive them as tax refunds. Put simply, tax paid by companies is credited back to company owners when profits are distributed. For Australian shareholders, the corporate tax bill vanishes. It is not a tax in any meaningful sense. It is a prepayment.

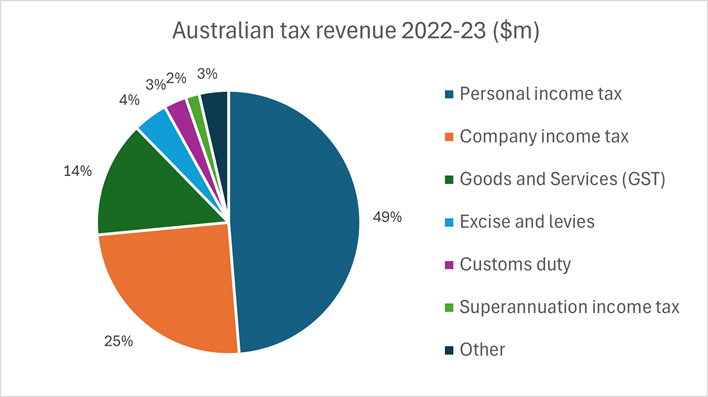

Source: Firstlinks; Parliamentary Budget Office, Australia’s Tax Mix, Appendix A.

That is why it is misleading to treat Australia’s 30% corporate tax rate as a heavy impost. For Australian investors in Australian companies, there is no company tax. The burden of corporate tax only truly falls on foreign investors, who cannot redeem franking credits.

This matters because business groups, many politicians and too many commentators continue to argue that Australia must slash its corporate tax rate to remain competitive and to incentivise capital investments. Charts are circulated showing Australia with one of the highest headline rates in the developed world. But these charts ignore imputation, marking them as misleading. Notably, the US Congressional Budget Office found that the average tax rate for US investors in Australia was 17%, but only 11% on new investments, making Australia’s effective tax rate one of the lowest in the world.

The critical point is that Australia is not a high company tax outlier.

Research, including that of Professor Peter Swan, confirms that franking credits are valued by the market. They increase share prices, reduce the cost of capital, and make investment in Australian companies more attractive. This is a structural advantage unique to Australia, and it should not be overlooked.

It is likely that much of the confusion in this debate stems from a broader misunderstanding about the nature of company capital. Is it controlled by company managers, to be allocated at their discretion, or does it belong to shareholders, who are the rightful owners of the enterprise?

Legally and economically, company capital belongs to the shareholders, and dividend imputation reflects that by pushing the incidence of tax to them. Yet company managers often prefer to maintain the illusion that profits are theirs to control and allocate. The spectre of a crushing corporate tax conveniently supports this view, lending weight to calls for changes that ultimately enhance managerial freedom rather than shareholder returns.

The real winners from lowering company taxes

The main winners from a company tax cut would not be Australian companies or their domestic shareholders. It would be foreign investors and shareholders in low-payout firms, where franking credits are not fully distributed. These are precisely the groups that cannot make full use of imputation. Lowering the corporate tax rate would increase after-tax returns for them, but at the cost of government revenue.

Would this encourage investment and productivity? The evidence is far from clear. Extra retained earnings in low-payout companies are not automatically channelled into productive growth. They may just as easily fuel wasteful empire-building or other agency costs. Even the Productivity Commission’s own modelling suggests a tax cut would deliver only a one-off lift to GDP of about 0.4%. Not nothing, but small beer compared with the claims often made.

This is why the corporate tax debate in Australia so often feels dishonest. The bogeyman of a crushing 30% rate is invoked as if it shackles every business in the country. But for most domestic investors it simply does not exist. It is a phantom, a myth perpetuated by those who either misunderstand the imputation system or prefer not to acknowledge it.

If the real objective is to attract more foreign capital, that is a legitimate debate to have. But let us be upfront about it. Lowering the corporate tax rate is a policy choice to privilege foreign investors at the expense of government revenue. It may or may not be wise, but it should not be justified with scare stories about Australian companies suffering under a tax that, for most, dissolves on contact.

Keyser Söze terrified people because they believed in him, not because they saw him. Australia’s corporate tax rate plays the same trick. The 30% headline rate is brandished like a weapon, but in practice, for most Australian shareholders, it evaporates. Until this is admitted, policy debates will keep chasing shadows instead of substance. The greatest trick Australia’s corporate tax regime ever pulled was convincing everyone it exists when, for most Australians, it really does not.

Peter Swan AO is emeritus professor of finance at the UNSW Sydney Business School. Dimitri Burshtein is a principal at Eminence Advisory.