Australians are retiring with unprecedented levels of wealth. This wealth, which is primarily held in housing, investment properties and superannuation, allows retirees to draw incomes to support their retirement.

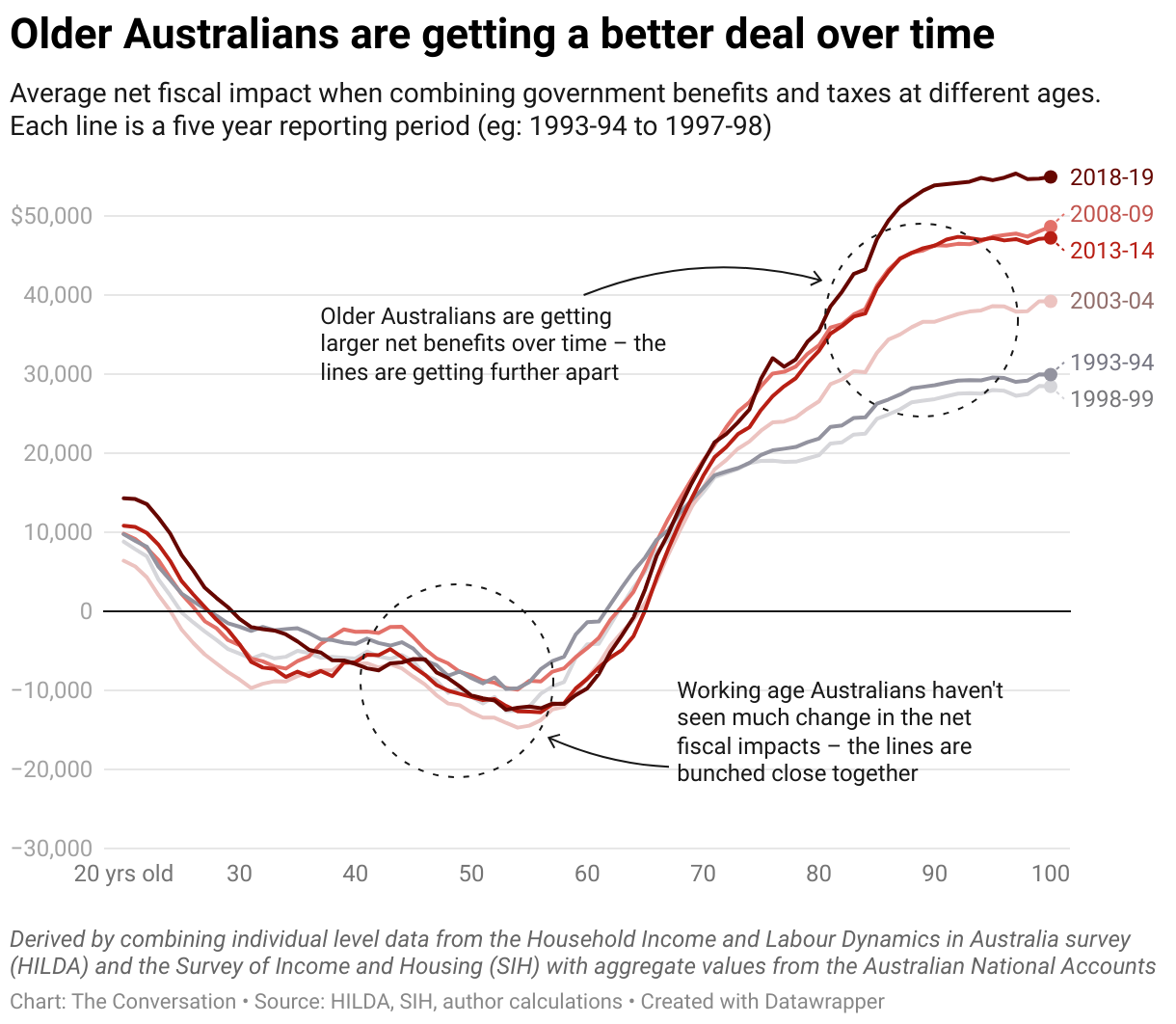

As Australians have become wealthier, we might expect government spending on social safety nets for older Australians to fall. Instead, we have seen these programs grow in real, per-person terms.

The overall result is older Australians have much higher incomes than previous generations of retirees. The average 75-year-old’s post-tax and transfer income 25 years ago was little more than 75% of an average Australian income. Today it equals the average Australian income.

Older Australians also enjoy a post-tax income one third higher than Australians aged 18–30.

This astonishing fact points to flaws in our tax and transfer system.

Older and wealthier than ever

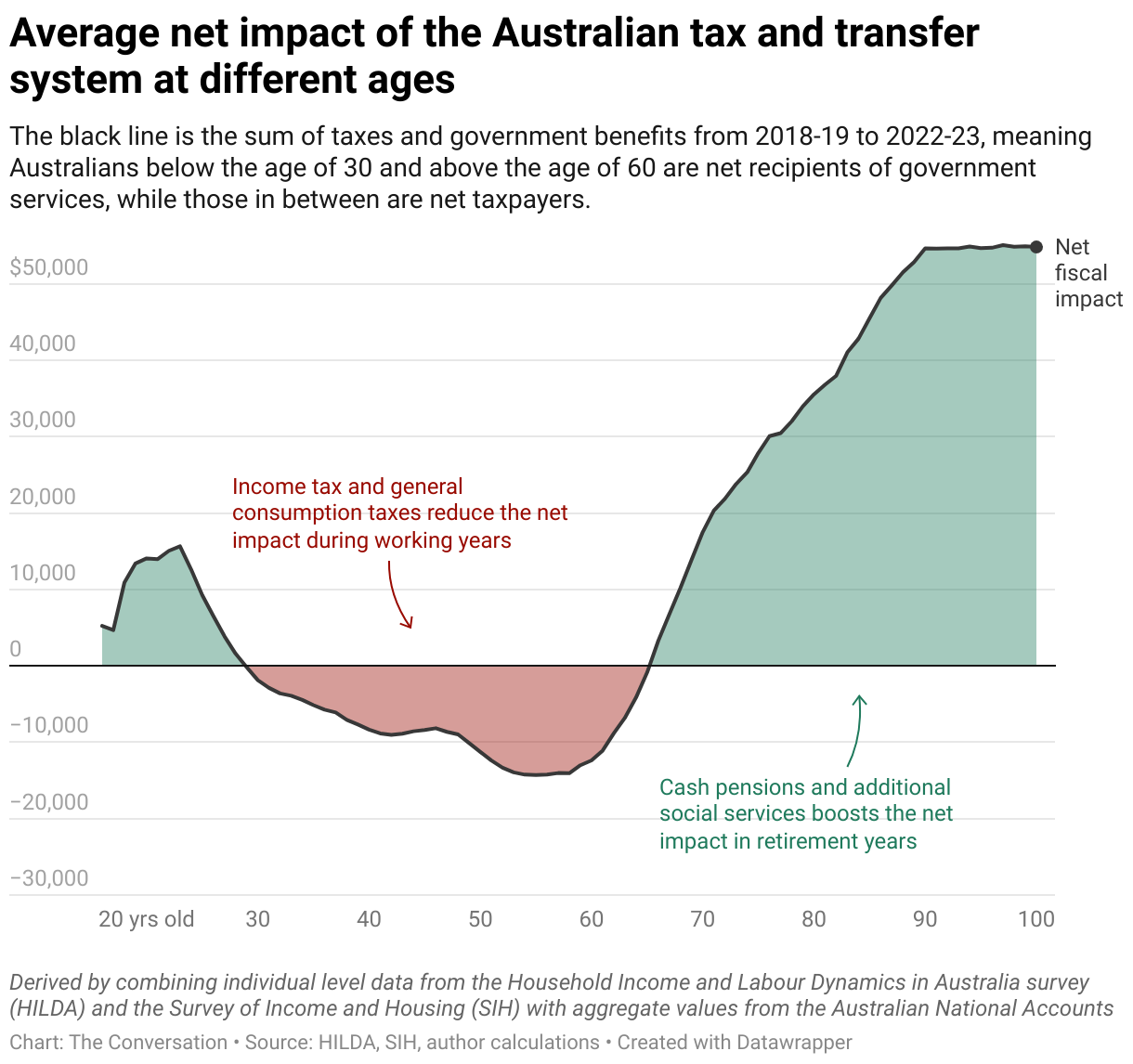

Our research shows the tax and transfer system treats people differently at different ages.

A “transfer”, in this context, is money people receive from the government, such as welfare payments. It also includes government provided services such as education, health care and aged care.

People receive benefits from the state as a child. They attend childcare paid for by government subsidies and they get a free (public) or subsidised (private) education.

They then contribute more in tax than they receive from government while at their most productive, before once again enjoying an excess of transfers (more payments received than tax paid) later in life, as their productivity declines and they enjoy retirement.

In our research, we first measure how private income throughout the life cycle has changed in the past three decades. This calculation includes income from all sources, including unrealised capital gains from housing and superannuation.

We found earnings have grown at all ages. Our peak earnings continue to occur in our 50s.

It also shows Australians are earning more passive income in retirement today than in earlier periods.

In the earlier periods of our study, older Australians earned relatively little income. The tax and transfer system provided income through the aged pension and in-kind support to give them an income similar to those at the beginning of their working lives.

In contrast, today’s average Australian in their 60s has a substantially higher private income and receives substantially more from the tax and transfer system. They end up with the post-tax income of an average 40-year-old (without the pressures of saving for the future or supporting a growing family).

This means the nature of the tax and transfer system has fundamentally changed in the past three decades.

While most of our system relies heavily on means testing, ensuring government support goes to those who need it most, much of our assistance to older Australians is disbursed on the basis of age.

Age used to be a good marker of disadvantage. This is no longer true.

Skewing the advantages

The evidence is stark: the Australian government’s relative expenditure on older Australians has increased significantly in recent decades, funded by those of working age.

At the same time, the wealth and incomes of those older Australians has increased more rapidly than for other age groups.

This is driven in part by good policy, ensuring Australians have strong incomes in retirement. We have succeeded in dramatically lifting the wellbeing of older Australians relative to several decades ago. Younger people today will similarly enjoy comfortable retirements.

But this significant change has several and serious implications for the future of Australia. These include the long-term sustainability of the federal budget and the broader design of the tax system. One third of total income is currently untaxed in our system. A dual income tax, which taxes all income from assets at a low, uniform rate, would go a long way towards fixing this problem.

Wealth over a lifetime

Governments support people to even out the amount of income they have throughout their lives. But do we have the balance right?

While younger Australians face buying a home and raising a family (while contributing 12.5% to superannuation), older Australians enjoy, largely unencumbered, similar levels of income (and often die with significant superannuation balances).

We are taking money from people at an age where they need it most and giving it back to them when they appear to need it less.

Sensible reform that helps people spend retirement incomes and provides insurance against the worst possible outcomes would help.

We don’t want to undo the policies that make older Australians wealthy but we need to make sure that future generations will have the same benefits.

What about housing?

Increases in house prices over the past decades have increased the wealth of older Australians, helping grow their private income in the form of both capital gains and imputed rent (what a homeowner would pay in rent).

This income has come at the expense of younger Australians and migrants buying into the housing market, effectively keeping them poorer for longer. For those whose parents have assets, the problem is short-lived or solved by the bank of mum and dad.

For those whose parents don’t have assets, they may be locked out of home ownership for life.

The real inequality issue is between those young people who will inherit assets and those who won’t.

What creates much of this housing inequity? Government policy.

Preferential tax treatment of housing increases demand and pushes up prices.

Zoning and planning regulations limiting new housing supply contribute around 40% to the price of houses in Sydney and Melbourne and a quarter of all land within ten kilometres of Sydney’s CBD is subject to heritage protections.

There are also many well-documented policies that discourage older Australians from downsizing. These include capital gains exemptions for houses homeowners live in, means test exemptions for owner-occupied housing, rates and utilities subsidies for older Australians, ageing in place programs, the lack of a broad-based property tax and stamp duty.

To the extent that housing prices are driven by government policies that restrict land supply, these policies should be reversed as a matter of urgency.

And in the decades to come?

The current tax and transfer system is spiralling down and unsustainable.

As the government’s obligations to older Australians (in pensions, in aged care and health care benefits) increase relative to the size of the economy, government will need to increase taxation on the productive sectors of the economy.

Postponed childbearing, exit from the workforce and other consequences will reduce the relative size of the economy’s productive sector, ultimately exacerbating the problem to the point of disaster.

Clearly, policy must address this downward spiral sooner than later.

Robert Breunig, Professor of Economics and Director, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.