The Australian investment landscape is set for another skirmish in the ongoing fee war. Recently, a new ASX300 exchange-traded fund launched with an expense ratio of 0.04%, challenging the incumbent and its 0.07% fee. Online, the excel models are already running hot in a ferocious contest over three-hundredths of a percentage point – a sum amounting to $30 a year on a $100,000 portfolio.

This forensic obsession with cost is not an accident. It is the natural result of a doctrine that has come to dominate modern finance: that the optimal path is paved with passive, market cap-weighted index funds. It is a philosophy that champions simplicity and low cost above all, offering an elegant solution that has become the comfortable default for millions. However, this narrow focus on explicit costs can create a significant opportunity cost, distracting from a far more consequential question.

What if the construction of the index itself is a more powerful driver of returns than the fee paid to track it? To question this default setting is often viewed as heresy. Let’s test the hypothesis.

In this article I will take the industry’s conventional benchmarks and assess them against their factor-tilted challengers. To ensure a robust comparison, we will deliberately handicap the challengers, subjecting them to their higher fees and a drag for trading costs – a penalty their cap-weighted parents do not pay. This creates a deliberately high hurdle for the factor strategies to overcome.

The results are illuminating.

The terms of engagement

Note: To avoid venturing into the world of financial advice I have avoided directly mentioning the underlying products that track these indices.

Here is exactly how I applied the expenses, ensuring a comparison grounded in real-world costs.

Each Index was debited a Management Expense Ratio (MER). The MSCI World Index parent portfolio was charged a 0.18% annual fee, while the MSCI World Factor Mix A-Series Index challenger paid the same 0.18%. Next came the handicap, applied only to the factor-tilts. On top of its MER, the Factor Mix A-Series was charged an additional 0.20% per annum 'turnover penalty' to account for the higher turnover costs of rebalancing its holdings.1

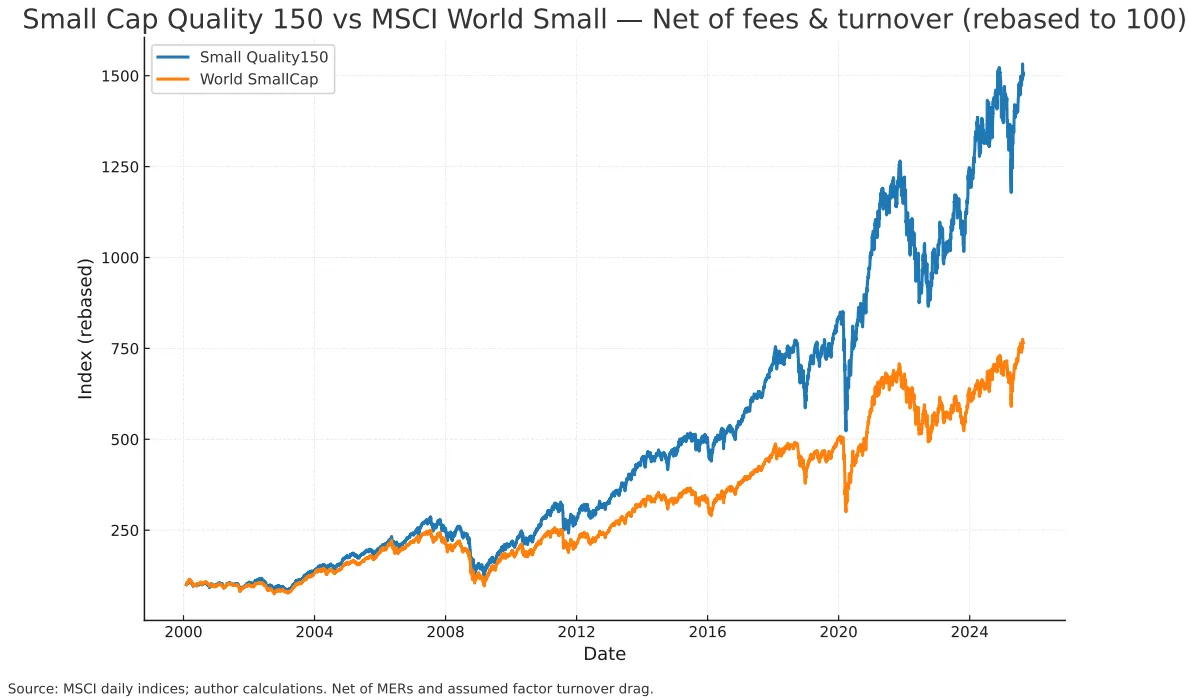

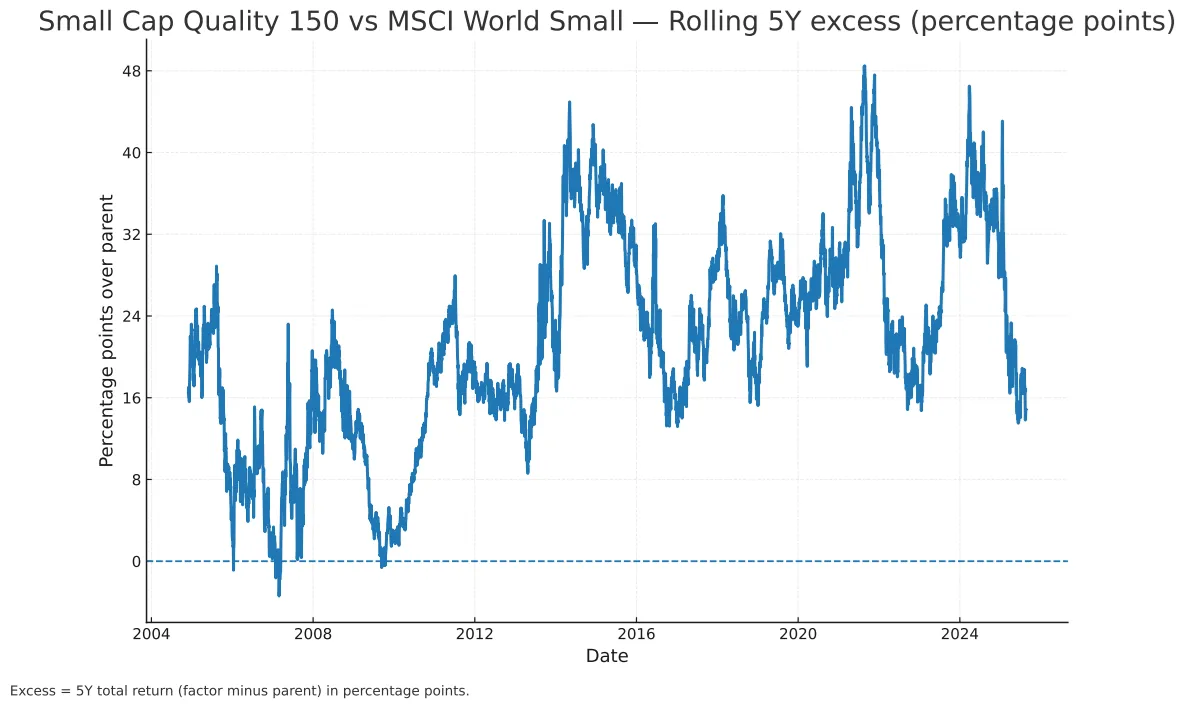

This asymmetric penalty was even harsher in other segments. In small caps, the MSCI World Small Cap Index is charged a 0.45% MER. The Small-Cap Quality Index factor-tilt is charged a higher 0.59% MER plus a 0.30% turnover drag.

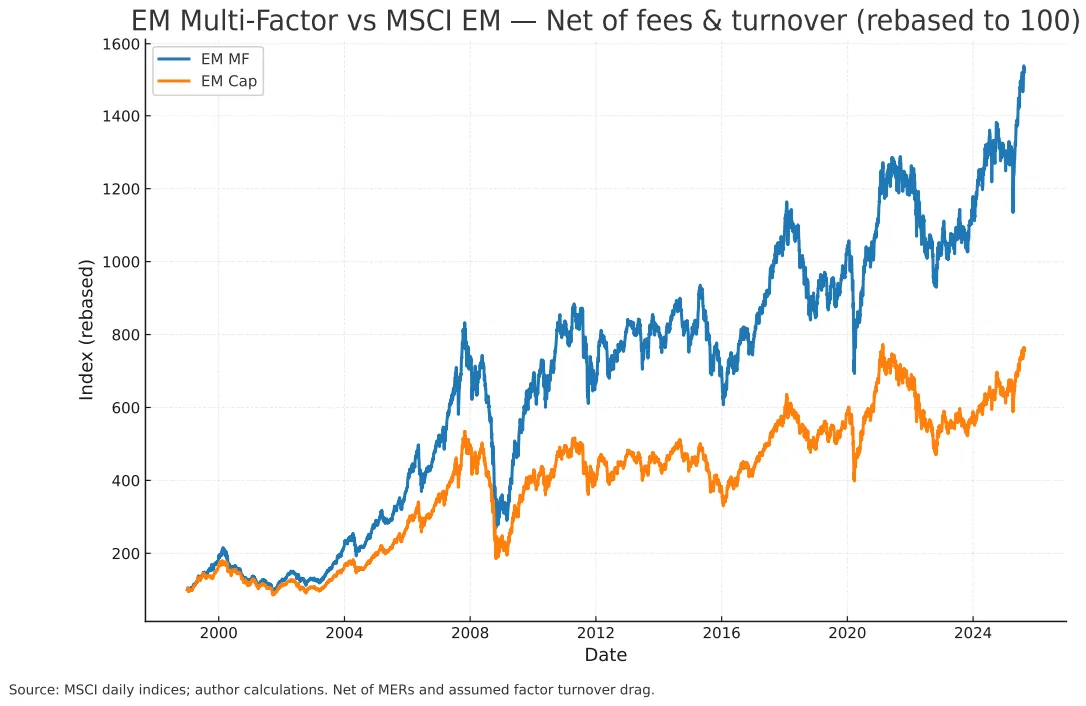

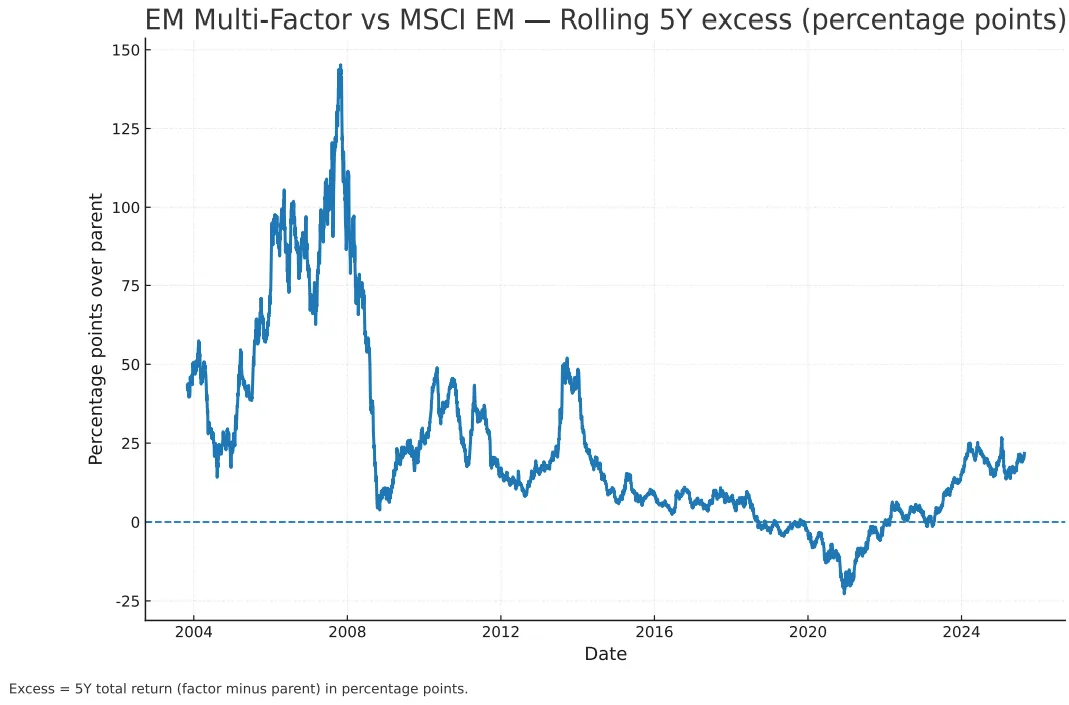

In emerging markets, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index pays 0.48%. The MSCI Emerging Markets Multi-Factor Index challenger is charged 0.69% plus another 0.30% turnover drag.

The factor portfolios were thus forced to compete under a realistic yet conservative cost disadvantage.

A consistent pattern of outperformance

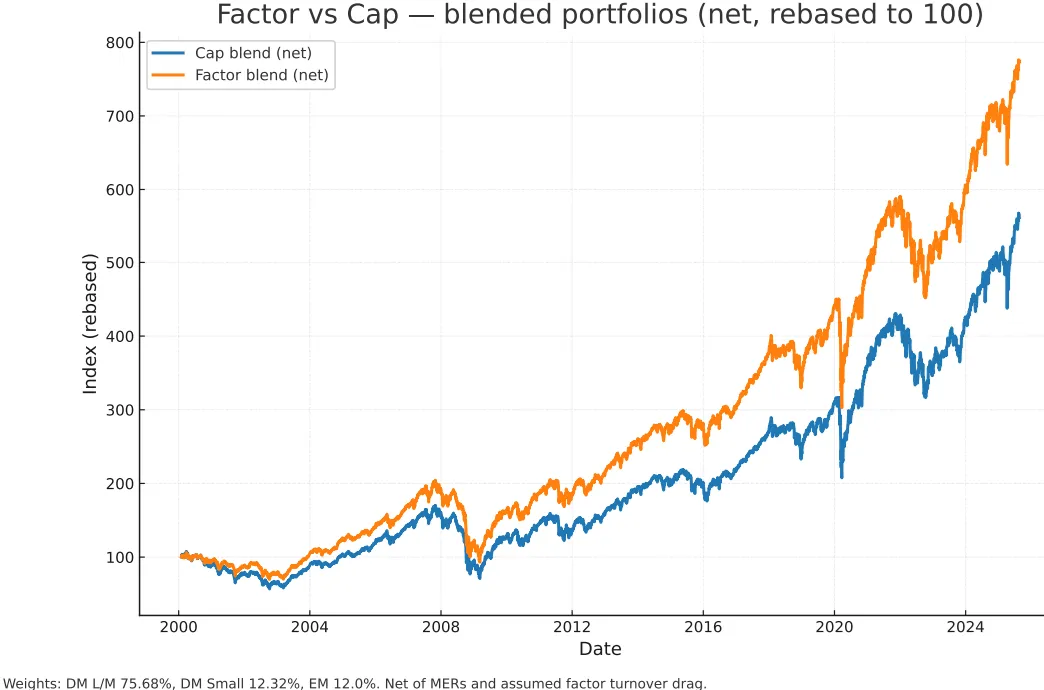

Let us begin with a globally blended portfolio, reflecting a typical investor allocation (75.68% developed markets, 12.32% small-cap, 12.0% EM). After all fees and tax-drags, the factor blend compounded at 8.36% per year. The conventional cap-weighted blend returned 7.01%.

This divergence resulted in the factor-tilted portfolio generating an annualised alpha of 1.8%, achieved with a superior risk-adjusted return (Sharpe ratio of 0.62 vs 0.50).

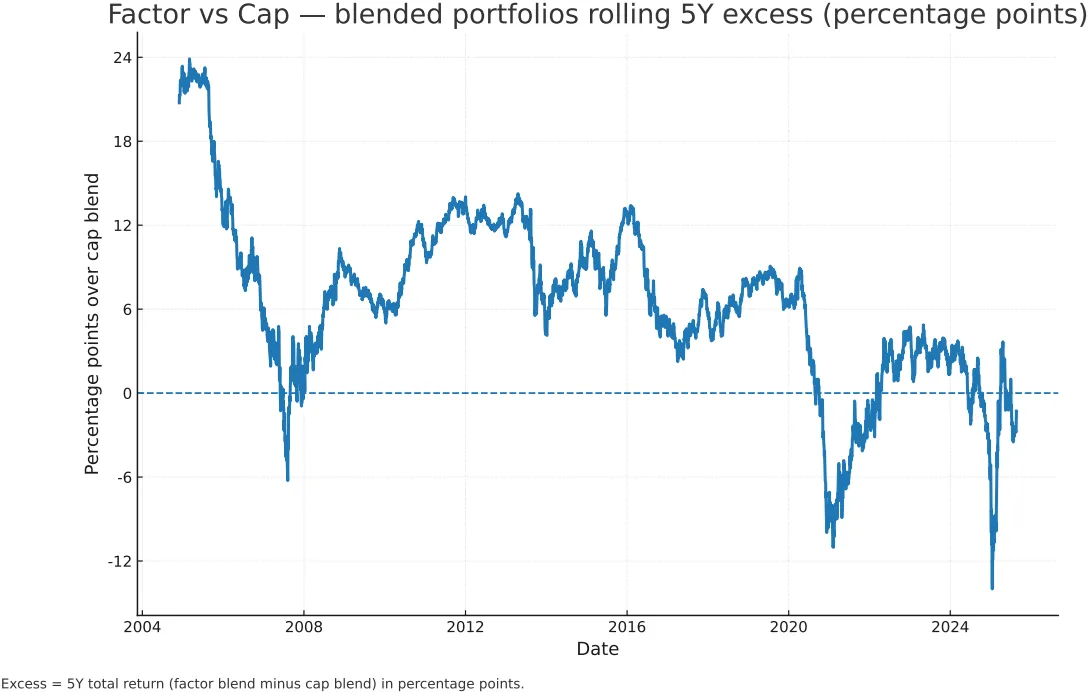

The factor-weighted portfolio outperformed the market cap weighted portfolio 87% of the time (based on 5-year rolling periods).

The outcome becomes clearer when inspecting the individual segments:

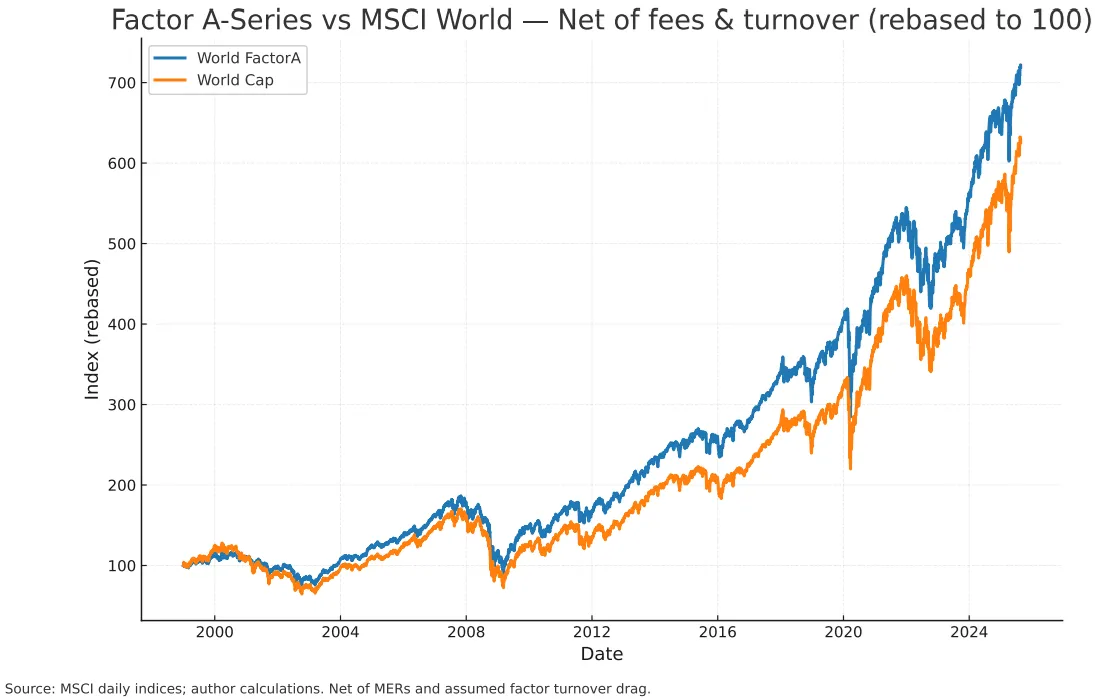

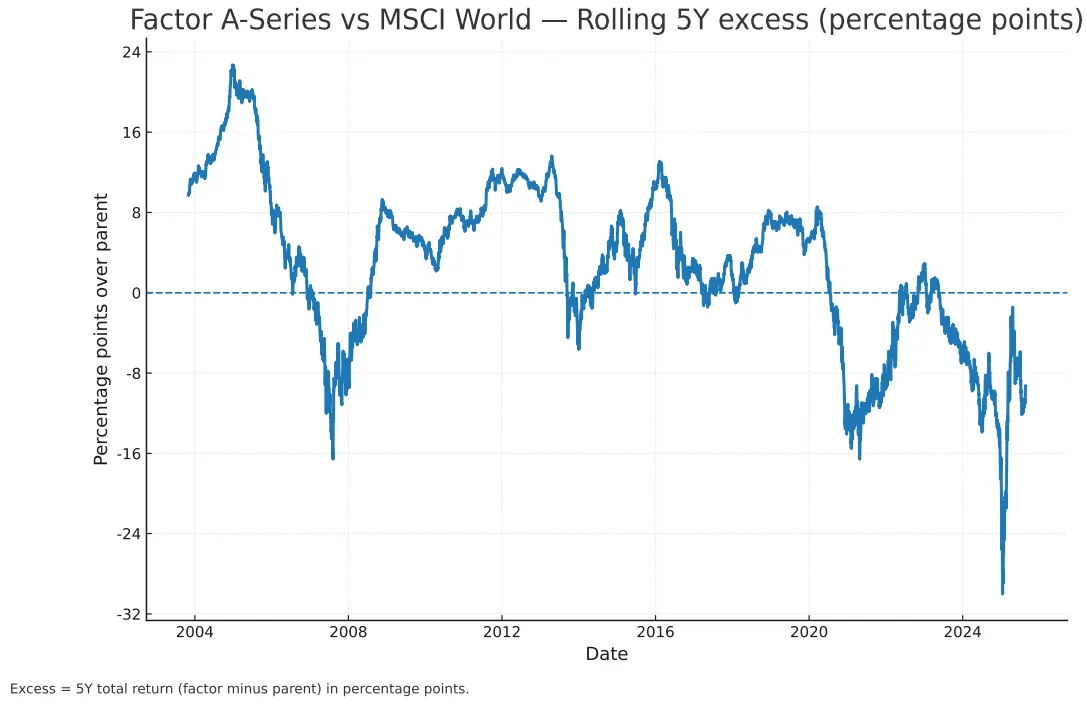

- Developed Markets: From 1 Jan 1999 to 21 Aug 2025, the MSCI World Factor A-Series delivered a net return of 7.69% to the parent’s (MSCI World) 7.13%, achieving this with a lower beta (0.87) (higher risk adjusted returns) and generating an annualised alpha of over 1.2%.

The multi-factor option outperformed the market-cap weighted methodology 68% of the time.

- Small-Caps: The effect was most pronounced here2. Since 1 Feb 2000, the MSCI World Small-Cap Quality Top 150 Index3 returned a net 11.23% per year, decisively outpacing the parent’s (MCSI World Small Cap) 8.32%.

The quality-tilted small cap portfolio outperformed in 99% of all rolling five-year windows.

- Emerging Markets: Even in this notoriously opaque segment, and after being charged nearly 1% in MER + turnover drag, the multi-factor challenger delivered 10.77% versus the parent’s 7.89%, winning in 85% of rolling five-year periods.4

The method behind the outperformance

These results are not a statistical accident. They are the outcome of strategies designed to harvest well-documented, academically rigorous sources of return known as 'factors'. The indices used in this analysis deliberately target exposures to Size, Value, Quality/Profitability, Low-Volatility, and Momentum – effects with decades of cross-market evidence first popularised by academic researchers Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.

The persistence of these factor premia is typically attributed to two main theories:

1. Risk-based explanations: These theories posit that the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) is incomplete, suggesting that other sources of systematic, undiversifiable risk exist beyond simple market exposure (beta). From this perspective, factor premia are the rational compensation investors demand for bearing these additional risks.

The Value premium, for instance, is often linked to 'financial distress' risk; value companies tend to be more mature, may have higher leverage, and are often more vulnerable to economic downturns. Their lower valuations reflect this heightened risk, and the premium is the reward for holding these stocks through periods of uncertainty.

Similarly, the Size premium is considered compensation for the risks inherent in smaller companies, which typically have less diversified revenue streams, more limited access to capital, and higher sensitivity to the business cycle compared to their larger counterparts. According to this view, the long-term outperformance of value and small-cap stocks is not a market inefficiency, but a fair payment for bearing specific economic risks not captured by market beta alone.

2. Behavioural explanations: Alternatively, behavioural theories argue that factor premia are the result of persistent and predictable cognitive biases among market participants. These systematic errors in judgment lead to mispricings that a disciplined strategy can systematically exploit. For example, the Value premium may be driven by overconfidence where investors become overly optimistic about 'glamour' growth stocks with compelling narratives, pushing their prices to unsustainable levels. The same extrapolation biases can fuel the Momentum premium, as investors project recent price trends far into the future.

The Quality and Low-Volatility anomalies are often attributed to a 'preference for lotteries', (such as 'meme-stocks' or eye-watering valuations for AI-adjacent stocks) where investors are drawn to speculative, high-risk stocks in the hope of outsized gains, causing them to overpay for these volatile assets. Consequently, stable, profitable companies tend to be systematically underpriced relative to their risk. From this viewpoint, factor investing is a form of arbitrage, capitalizing not on risk, but on the enduring patterns of human psychology.

Modern index construction is engineered to maximise exposure to these factors while implementing rules that contain turnover and minimise trading costs, which is why the real-world performance has remained robust.

The price of a differentiated return

This outperformance is not, however, always a 'free lunch'. There are extended periods where a factor-tilted approach will underperform a cap-weighted benchmark. When a market becomes fixated on a narrow group of glamour stocks – as it did with US tech megacaps from 2019 to 2024 – any diversified strategy is guaranteed to lag. These 'factor winters' are the price of admission for accessing the long-term premium.

A sceptic might correctly observe that the data presented here, from 1999 to the present, represents a mere quarter-century – a significant but not exhaustive period in financial history. However, it would be a mistake to assume these factor premia are a recent phenomenon.

The academic foundations for these strategies are built upon evidence that stretches back much further. The Fama-French three-factor model, a cornerstone of modern financial economics, documented the persistence of the Value and Size premia in US markets with data reaching as far back as 1926. Similar long-term studies across various international markets have repeatedly confirmed the robustness of these effects – including Momentum, Quality, and Low Volatility – over many decades and through numerous economic regimes. The outperformance shown in this analysis is therefore not an isolated anomaly of the modern era, but rather a recent confirmation of some of the most persistent and well-documented sources of return in financial history.

It is also worth noting the current state of the discourse. While the financial media and online forums fixate on a narrow cohort of popular technology stocks or the minutiae of cap-weighted fund fees, the academically robust factors such as value, size, and low volatility remain deeply unfashionable. In the world of investing, this is rarely a bad sign. Historically, the most rewarding returns are not found in the most crowded trades but in the most neglected ones. A lack of popular enthusiasm is often a harbinger of higher potential returns, as the premia associated with these strategies are not being competed away by a stampeding herd.

The debate over a few basis points on a management fee will continue to rage. It is, after all, a simple and tangible metric to anchor on. But the data presented here suggests it is a profoundly misguided obsession. The true cost of an investment is not found in the fractions of a per cent listed on a fact sheet, but in the percentage points of performance left on the table by choosing a suboptimal index. The conventional, cap-weighted portfolio may be the cheapest and simplest path, but the evidence is clear: it is far from the most profitable one.

1 The additional turnover penalties of +0.20% p.a. for the A-Series and +0.30% p.a. for the Small-Cap Quality and EM Multi-Factor sleeves were chosen as all-in estimate of implementation costs based on three observations. First, MSCI's factor indices are explicitly engineered with buffers and constraints to moderate turnover, making them cost-efficient to implement. Second, empirical studies of transaction costs show that realised costs for broad, rules-based equity strategies are typically in the low tens of basis points annually, meaning the 20-30 bps assumption is a reasonable and not aggressive overlay (see AQR article) Finally, real-world tracking differences for passive funds often hew closely to their MER, as managers can offset trading friction through techniques like internal crossing and securities lending. Therefore, applying an additional 20-30 bps penalty on top of the MER serves as a reasonable safety margin.

2 See the litany of research showing how the increasing “junkiness” of the small-cap market-weighted indices creates a significant drag.

3 The small cap quality factor used here is ex-Australia, compared to an index which includes Australia. I think this is negligible in terms of its effect on the discussion at hand.

4 There is significant research that adding a factor tilt to EM that re-weights shareholder returns (Quality, Dividend Yield/Value) helps with the ongoing dilution/issuance drag associated with EM exposure.

“Macro Torque” is an Australian Engineer (with a Finance Masters) who writes about Finance and Economics. This article is reproduced with permission from the Macro Torque substack blog (@macrotorque).