Five years ago this week, the Rudd Government launched its first stimulus spending package to ward off a recession, and placed a guarantee on bank deposits as money was flowing out of regional banks and small financial institutions at the height of the GFC. The moves followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008, and Wayne Swan commented that at the IMF meeting held at the time, he could see the “fear in the face of the delegates”.

So we’ve seen ‘fifth anniversary’ newspaper stories recalling the traumatic events of the crisis, and the former executives of Lehman, JP Morgan, US Treasury and Bank of America have appeared in television specials, explaining their role in saving the day while all around them panicked.

Market meltdown hit borrowers first

In fact, the GFC started a year earlier in the global credit markets, but the equity markets ignored it. With hindsight, everyone had the chance to exit shares at elevated prices with plenty of notice, as the credit markets were screaming for all to see, in every part of the world.

It hit the multi billion dollar borrowing programme I was managing a full 13 months before the Lehman crisis.

In the early evening of Thursday, 9 August 2007, I received a phone call at home from a Citibank dealer in London. For many years at Colonial First State, we had been issuing short term notes in the Euromarkets to finance the largest geared fund in Australia, and some notes routinely rolled over almost every night. Europe was an excellent source of inexpensive funding, sometimes swapping into Australian dollars at below the domestic bank bill rate – amazingly cheap for equity leverage. We posted issuing levels at the end of each Australian day and the London dealers at investment banks like Citi and Warburgs could transact at those spreads without further reference. At the time of the call, we had over a billion dollars on issue in Europe, and this night, $US50 million was maturing.

"We can't rollover your paper this morning. There are no bids in the market," said the Citibank dealer.

At first, while unusual, this was not alarming, as pricing levels between issuer and dealer are subject to negotiation and posturing. I asked for more details, and said we were willing to pay a few points more if necessary.

"You don't understand," he said. "It's not a matter of price. There are no bids on anything".

And that night, now over six years ago, the GFC started. I immediately turned on my lap top, and a quick scan of financial websites confirmed what had spooked the market. BNP Paribas had suspended redemptions on three of its money market funds, and to quote them, “The complete evaporation of liquidity in certain market segments of the US securitisation market has made it impossible to value certain assets fairly regardless of their quality or credit rating … We are therefore unable to calculate a reliable net asset value (NAV) for the funds.”

The US sub-prime crisis had come to Europe. The entire billion dollars of notes matured over the following months without a single rollover at any price. If ever confirmation was needed of the merit of diversified funding sources, this was it.

No institutional borrower should ever forget that lesson.

Complete change in bank willingness to lend

Initially, there was no way of knowing if the crisis would last a week or a year. The remaining $4 billion of our $5 billion borrowing programme was onshore in Australia, including short term notes issued into the market and direct bank lines. Although these sources proved more resilient for a well-established local borrower, there was a massive transfer of negotiating power to lenders and investors. A cash manager like Tony Togher in the Colonial First State funds operation suddenly became far more powerful, with tens of billions of cash from his funds to dole out to desperate borrowers.

A year earlier, banks had been calling at our doors to lend as much money as we wanted, and we even had one major bank wanting to fund the entire multi-billion dollar facility. The margin on billions of dollars of bank debt for a geared fund reached a low of 0.40%. After the crisis hit, the banks had their own funding problems, both in quantity and price, as short-term wholesale facilities could not be rolled over. For a long time, banks would not even lend to other banks.

Many long-established relationships disappeared. Suncorp wanted its money back as soon as possible as they withdrew from corporate lending. Bank of America significantly reduced its facility, and only retained a small amount after much persuasion. Westdeutsche Landesbank was in a dire state in its home market and left Australia completely, never to return. HBOS plc withdrew and BNP Paribas was no longer interested in lending. All banks demanded major increases in lending margins, which more than tripled to over 1.30% as facilities matured. Many of the foreign banks that had been useful competitors with the major banks for corporate borrowers had to focus on funding problems in their home countries.

While in our case, the major banks continued as supporters, they withdrew loan facilities from thousands of corporate customers across the country. They were preserving their own funding and reducing lending as the market remained in crisis mode. Banks are the plumbing that makes liquidity in the financial system flow, the transmission mechanism through which the government and regulators operate, and the banks were frightened.

It’s easy to forget what fretful times these were, and how many thought the entire system was about to collapse. Meetings between borrowers and lenders were tense and we used every method we could imagine to retain our funding. We even threatened that Colonial First State fund managers would withdraw their cash from the banks, although we had no power to make it happen. All borrowing spreads widened dramatically, and many note issuing programmes collapsed. Australian banks focussed heavily on building domestic retail funding bases, and the spread between term deposit and bank bill rates rose to levels never seen before.

Sharemarkets remained strong for many months

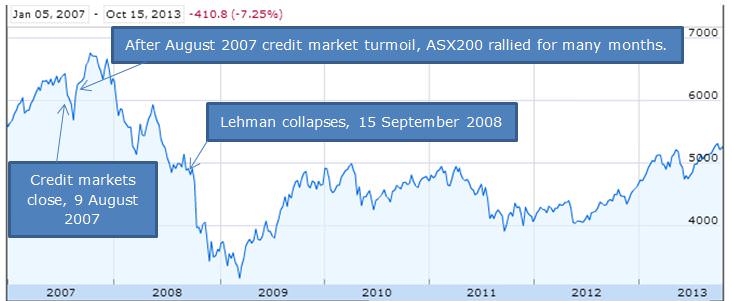

And yet, while debt markets were in turmoil, equity markets remained strong for many months, with a high on 12 October and another rally to similar levels on 7 December, as shown below. It was an extraordinary disconnect. Either the bond market or the equity market was wrong, but we were not sure which. I recall talking to Warren Bird at the time (see previous article), who was surprised by the rising equity markets, which he believed did not appreciate the stresses that the credit markets were signalling.

S&P/ASX200 from January 2007 to October 2013

Source: Google Finance.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers was not until 15 September 2008, over a year later. Merrill Lynch was rescued by Bank of America, and the US Federal Reserve bailed out JP Morgan Chase and AIG, which in turn saved Goldman Sachs. So much for the free market bastions of Wall Street.

It's not over yet

In this week where the debt-paying capacity of the greatest credit in the world, the US Government, has been in doubt, it’s worth recalling these events of six years ago, and the importance of confidence in the global financial system. There was a severe loss of funding for businesses needing money to grow and employ people, banks stopped dealing with each other and governments around the world had to step in and guarantee their banks. The financing problem is far from solved, and it has spread to some of the (formerly) best sovereign names in the world.

While countries can borrow to save their banks, who can borrow to save the countries? I expect that six years from now, we'll still be trying to sort out the mess.