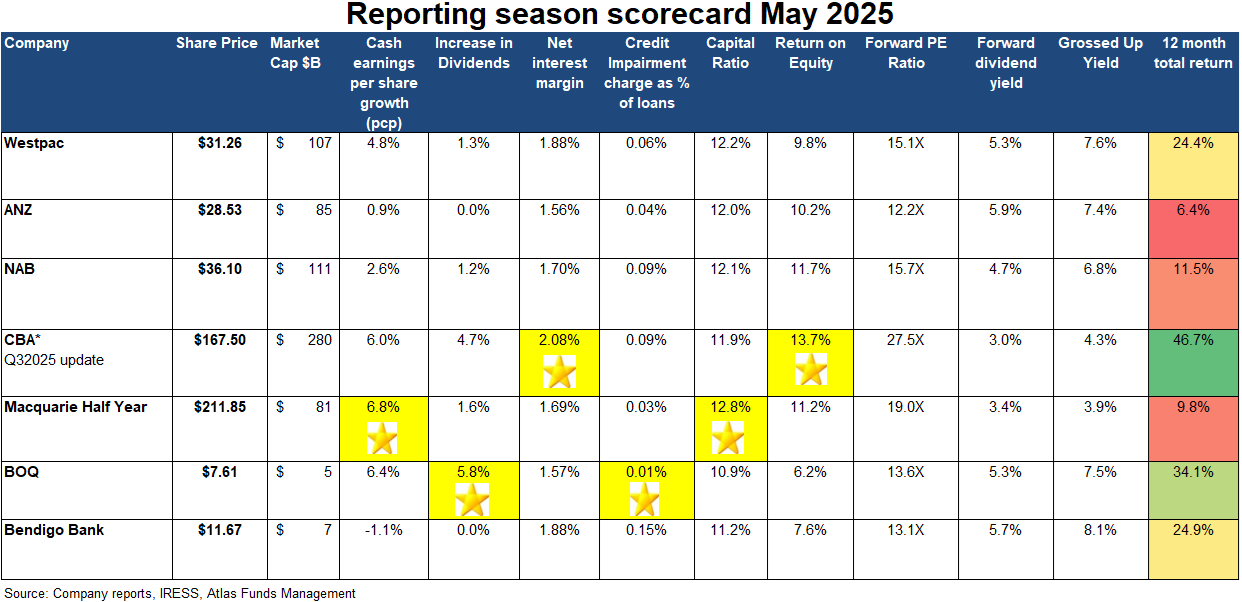

The May 2025 bank reporting season was highly anticipated by investors, more so than usual. Many professional fund managers sold down their bank exposures in early 2024 due to concerns about recession, rising bad debts, and valuation concerns in the case of Commonwealth Bank. Selling the banks in 2024 proved to be a very painful trade for many fund managers, with the banks outperforming strongly last year. Indeed, the banks seemed poised for a big fall, with global economic uncertainty following President Donald Trump's ‘Liberation Day’, which sent the ASX200 down 14% from its highs in February. However, the prophesied (and hoped for by those short the banks) doom and gloom for Australia's banks did not eventuate this May, with all banks growing profits and again revealing minuscule bad debts.

In this piece, we look at the major themes that played out over the May 2025 bank reporting season in the over 700 pages of financial results released, including the regional banks, awarding gold stars based on their performance over the last six months. Even for investors that don't own the banks, looking closely at their results provides a window into the financial health of Australia.

Margin pressure

Net interest margins are always a major topic during the banks' reporting season, with most investors going straight to the slide on margin movements in the immense Investor Discussion Packs. Banks earn a net interest margin (Interest Received - Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] by lending out funds at a higher rate than borrowing these funds from depositors or wholesale money markets.

Whilst net interest margins came under pressure for the banks this half, most were able to offset lower margins with higher loan growth. For example, Westpac's net interest margin decreased by 0.09% over the first half of 2025 to 1.88%. Although it is disappointing to have a lower margin, Westpac was able to grow its loan portfolio by $18 billion over the half, taking its loan book to $825 billion. Following the combination of a lower interest margin and higher loan portfolio, Westpac's interest income was actually flat in the last half, despite the lower margin.

Typically, Westpac and Commonwealth Bank enjoy a higher net interest margin than ANZ and NAB due to their higher weighting to mortgages, which enjoy a higher net interest margin than corporations that canvass banks in Japan or Europe for borrowing needs. In the first half of 2025, ANZ, Macquarie and Westpac saw small decreases in their net interest margins, with NAB able to hold their steady across the half. All the banks mentioned higher competition for loans, though this was tough to detect in their financial results, with all banks doing a good job growing their loan books to offset the margins.

Bad debts remain extremely low

Bad debts continued to remain low in 2025, with all the banks reporting extremely low loan losses. Bank of Queensland reported the lowest bad debts, 0.01% of gross loans, reflecting disciplined growth in their loan book, with all the big banks with less than 0.1% of gross debts being bad debts.

The level of loan losses is important for investors as high loan losses reduce profits, and erodes a bank's capital base. This reporting season has seen low bad debts translated into better-than-expected profits and, thus, higher dividends.

Atlas sees that the low level of bad debts is a combination of the prudent management of risks in the loan book, low unemployment and more conservative lending than we saw from the banks 2000-07. However, it would be disingenuous to attribute current low bad debts entirely to prudent lending from the banks. APRA's capital requirements announced in 2016 in response to the Basel III reforms to global banking effectively restrict banks from lending to developers that have not pre-sold 100% of their development and have a maximum loan-to-value (LVR) ratio on developments of around 65%. These requirements have seen developers switch to non-bank lenders and private credit funds that are not encumbered by these requirements.

We believe the loans to developers, property syndicates, and troubled industrial companies that are impaired now sit with non-bank lenders and private debt funds rather than the big four banks. What we have seen in 2024 and 2025 is signs of stress in private credit funds, with various funds converting non-performing loans into private equity stakes and getting into residential property development as loans went south. While an APRA-regulated bank would have to declare this as a bad debt, private credit funds have been slow to record these as losses.

Not the banks of 2007

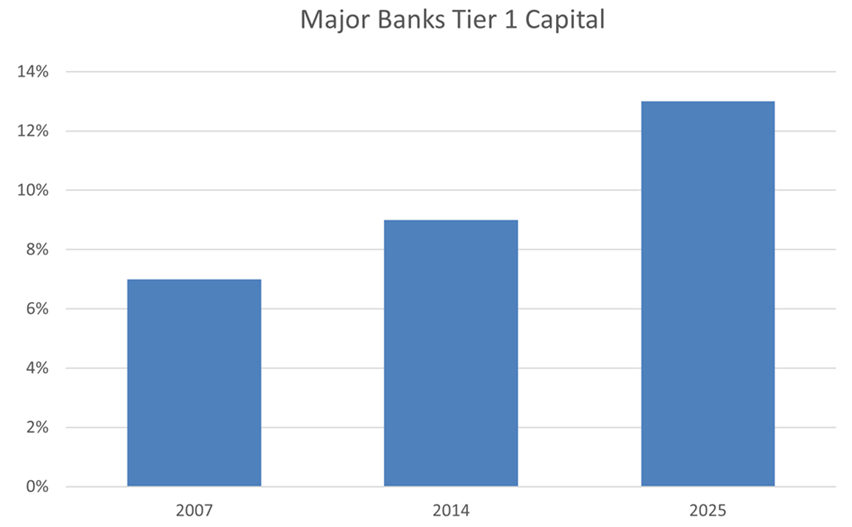

Capital ratio is the minimum capital requirement that financial institutions in Australia must maintain to weather the potential loan losses. The bank regulator, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), has mandated that banks hold a minimum of 10.5% of capital against their loans, significantly higher than the 5% requirement pre-GFC.

Requiring banks to hold high levels of capital is not done to protect bank investors but rather to avoid the spectre of taxpayers having to bail out banks. In 2008, US taxpayers were forced to support Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America, and British taxpayers dipping into their pockets to stop RBS, Northern Rock and Lloyds Bank going under. The Australian banks were better placed in 2008 and did not require explicit injections of government funds; the optics of bankers in three-thousand-dollar suits asking for taxpayer assistance is not good. Overall, the major Australian banks hold significantly more capital backing their loans in 2025 than they were pre-GFC or even ten years ago. Better capitalised banks are safer investments for both investors and depositors.

While the bank management teams congratulate their prudence in holding such high levels of capital, those with longer memories will recall the histrionic statements in 2015 when APRA forced the banks to raise $13.5 billion in extra capital. These capital raises were unusual as they were not made in response to a recession but rather to strengthen the banking system's resilience against potential financial crises.

In December 2024, APRA announced that additional tier 1 capital (bank hybrid notes) would be phased out of bank prudential frameworks. This will not be a large problem for the big banks, with all of them finishing the half with over 12% capital ratios. As many of these hybrids had franking credits attached to their coupon payments, the phasing out of hybrids see franking credits build up on bank balance sheets.

Buybacks

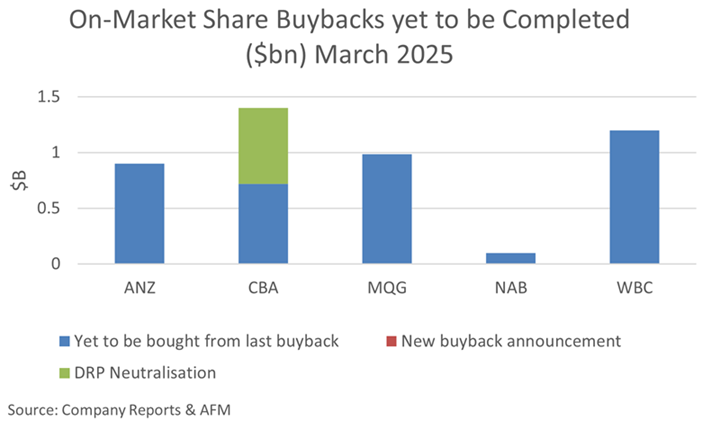

Buying back shares on the market and then cancelling them is positive for both shareholders as it reduces the divisor on future bank profits, and bank management teams are awarded bonuses based on their return on equity (ROE). ROE increases as buying back shares reduces the equity divided into a bank's return. Over the past few years, buy-backs have provided a consistent tailwind to bank share prices, with the banks themselves buying between 5-10% of the average daily volume on the ASX and then cancelling the shares. For example, since March 2022, Westpac has reduced its outstanding shares by 7%, buying back $7.5 billion in shares. Atlas has been reticent to swim against the tide of share buy-backs.

Whilst no new buy-backs were announced during this bank reporting season, the banks still have large buy-backs to complete from previous years in addition to the neutralisation of the Dividend Reinvestment Plans (DRP) and, in the case of Macquarie Bank, neutralise the impact of shares issued by their Employee Share Plan. This should see $5.7 billion of bank shares bought back and cancelled in 2025 and will limit the impact of large market falls.

Dividends

In the May 2025 bank reporting season, the banks announced smaller increases in dividends than we have seen over the last few years, with the average dividend increase across the big banks being 1%. Of the big 4 banks, Commonwealth Bank had the largest dividend increase of 2.1%, with ANZ at the other end, holding the dividend the same as they did last year. These dividend increases were largely a byproduct of on-market share buy-backs that have been conducted over the last few years. For example, since November 2021, Westpac has reduced its share count by 7% after buying back $7.5 billion in shares, with other banks in similar stead.

Regional banks

The regional banks walked away with two stars, being awarded to the Bank of Queensland, one for increasing dividends and one for low bad debts. In the past decade, the regionals have not seen many stars awarded. BOQ's low bad debts are slightly below the other banks, and its dividend increase of 5.8% benefits from timing as it followed a 15% cut in the dividend in May 2024.

In Australia, the big four banks dominate with a combined market share of 74%, following ANZ's successful acquisition of Suncorp Bank. The closest to breaking into the market is Macquarie, with close to 6% of the market share, followed by the two regional lenders of Bank of Queensland and Bendigo Bank, with a 3% market share each.

As we have seen in the bank matrix at the top, the regional banks face a competitive disadvantage when compared to the major banks, typically enjoying lower net interest margins and lower return on equity. This occurs because they have a higher capital cost than the major banks. Here, wholesale funders require higher coupons on their bonds to offset their higher risks and greater geographic concentration. Additionally, the regional banks have limited access to the large pools of corporate transaction account balances that have historically paid minimal interest rates.

Our take

Overall, we are happy with the financial results from the banks owned by the Atlas Australian Equity Portfolio in May. The three main overweight positions, ANZ and Westpac, maintained or increased their dividends, and Macquarie Bank showed a 30% increase in net profits in the second half, which also guided to increased profits in FY26.

All banks showed solid net interest margins, low bad debts, and good cost control. In 2026, the banks will all have cleaner loan books, more consistent earnings and a greater margin of safety than they have had in the past. In a turbulent world with weekly changes in trade policies, Australia's major banks are likely to positively surprise the market, operating in a small oligopolistic fishpond, sheltered from both new competition and global storms. As we saw in April, many foreign investors find our ‘boring’ banks quite attractive during global instability.

Hugh Dive is Chief Investment Officer of Atlas Funds Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.