“Don't worry, I won't hurt you, I only want you to have some fun”

Prince “1999”

On 9 July this year, an Australian Financial Review article[1] suggested that major non-for-profit (NFP) superannuation funds, faced with recent underperformance by domestic equity managers, would move to carve out the weightings of banking securities and index them within their portfolios. And it would allow appointed active managers to manage on an ex-banking sector basis, reducing their fee stream by roughly 25%.

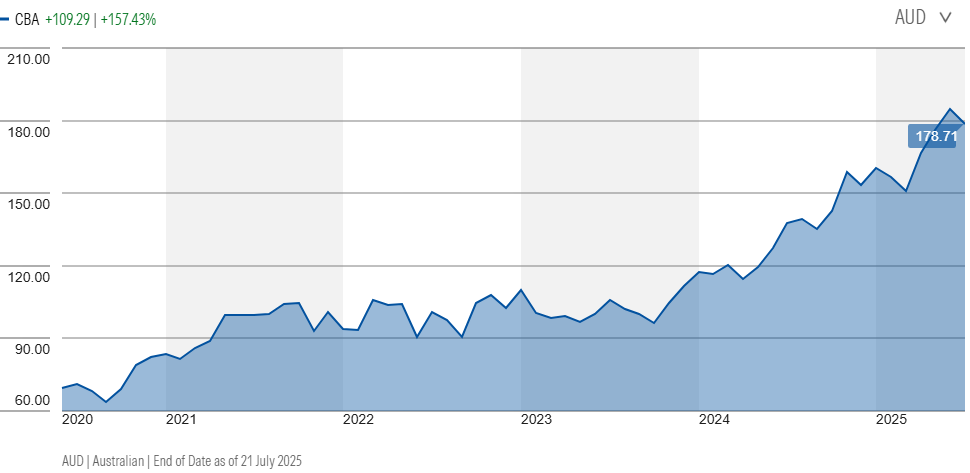

This is in response to most active managers underweighting a single security – Commonwealth Bank – accounting for 12% of the ASX200 index and returning ~20.5% year to date, twice the index measure. On consensus estimates for FY26, CBA shares trade at 29x forecast EPS of $6.32, a meagre 2.74% dividend yield, 4x book value and while earning an ROE of 13.6%. As a crude comparison, the bluest chip US bank, JP Morgan Chase, trades at 14.4x forward earnings generated by a 16.3% ROE and 2.2x forward book value.[2] Notably, the CBA estimates rest upon a pedestal of credit impairment charges equating to 7 basis points of gross loans and advances.

The AFR article contained no names or attribution and may have been an interesting piece of balloon floating by an enterprising allocator. If so, I couldn’t disagree more. If not, some highly remunerated allocators have short memories, especially considering a significant anniversary just a few months ago.

Source: Morningstar.com.au

Indexing and its origins

In 1999, aside from panicking about the Year 2000 problem, merging with SFE and moving to T+3, the ASX spent considerable energy working out how to rejig the All Ordinaries index, created from 1 January 1980 to replace the different Melbourne and Sydney Stock Exchange Indices. At that time, just over a year after ASX’s demutualisation and public listing, it was starting to get to grips with the various burgeoning income streams that the process of ‘commercialisation’ had stumbled across.

One of the most lucrative, since it is a natural monopoly, is the ownership of its share price data – live and historic – from which the various indices are derived. If you own shares in one of the few globally listed market makers such as Virtu Financial (NYSE: VIRT) or Flow Traders (Euronext Amsterdam: FLOW) you will know their perennial bugbear is the charges for data and inter-connects with exchanges. The ASX doesn’t miss and the revenue from the data component grows steadily at around 8% a year. Nice annuity. The ASX were especially smart by entering an alliance with Standard and Poor’s to gain the ‘S&P’ branding.

Most folks think indices are now just pre-cursors for exchange-traded products and derivatives such as futures. That’s hardly surprising given the flows into such investment options and the subsequent benefit to investors in companies such as MSCI (floated in 2007 by Morgan Stanley, and up some 32-fold from the $18 IPO price to $577 in the intervening period). If you are a US-educated investor, by and large indices are created as a proxy to measure performance of markets or stock groups; this reflects the history of the first index – the Dow Jones Railroads in 1884 and two years later, the world’s most famous measure the Dow Jones Industrial Average with its price weighted construction. Whilst arithmetically nonsensical, it has worked rather well as a proxy versus its float or market capitalization weighted counterparts.

In the UK, however, index construction originates from a very different and most relevant place for our argument: the Institute of Actuaries. Actuaries were responsible for the first UK shares indices in 1929. In 1962, they teamed up with the Financial Times which had been publishing the FT Index since 1935 (originally as the Financial News Index) and the London Stock Exchange to create the FTSE Actuaries All Share Index. Given I started my investment career in the London-based investment department of the UK’s then largest life assurance company, Prudential Assurance, asset allocation and performance benchmark measurement were crucial given the life assurance/insurance liabilities to be funded from premiums earned. As the world has increasingly moved away from ‘defined benefit/payout’ products to a unitised ‘accumulation’ world, where the consumer accepts investment risk with no liability to the provider, so has advisers and allocators willingness to be more permissive with benchmarks.

However, that doesn’t absolve the superannuation fund provider from acknowledgement of the investor’s ultimate liability, being their spending power in retirement. In my opinion, this is the obligation about which the anonymous NFP allocator cited in the AFR article has forgotten. Attempts to distort the benchmark and ‘lock in’ an index position in banking securities is cementing a fixed weighting of banking stocks- one of which is farcically expensive - into the superannuant’s future spending capacity. I find that horrifying.

We’ve been here before

So what of 1999? Any active Australian equity funds manager at the time – including myself – can remember a six-month period from October 1999 to March 2000 (when the index construction changed[3]) where one company dominated your world: News Corporation.

At end October 1999, News Corp’s two listed securities (then NCP and NCPDP, the higher dividend preference shares) had a combined market capitalisation of A$45.5billion, being 8.8% of the All Ordinaries capitalisation of $514.2 billion. In the subsequent five months, News Corp was involved in a number of minor deals: sale of 50% of Fox Sports, sale of German assets, divestment of Ansett and AWAS, an investment in OneTel whilst the profitability of its cable programming business was starting to accelerate. In addition, there was strong speculation regarding the ultimate future of its satellite assets. However, with the benefit of hindsight, nothing earth shattering to radically change the ultimate value of the company such as a spin-off, or major divestment or overall significant earnings growth.

With the dot-com bubble in full flight, egregious valuations were put forward for anything perceived to be able to utilise the Internet to advantage – ironically except banks where it transformed their business, with a permanent reduction in costs. However, News Corp was at the forefront of every rumour on new business initiatives, being the country’s foremost media owner at the time, yet without really executing anything of meaning at that time. In the subsequent four and a half months, News Corp ordinary shares advanced from $11.34[4] at end October 1999 to a peak of $26.20 on 22 March 2000 – a 96% gain. For a brief moment in time, News Corp represented over 17% of the All Ordinaries index, whilst trading on a forward P/E in the 70’s, and with its near $100 billion market capitalisation at the time, was priced at more than the entire listed resources sector[5].

Imagine you had a zero weighting in the shares on 31 October 1999? You would have lagged the All Ordinaries by over 8.5% in the subsequent 18 weeks. So to ‘correct’ for this irrationality, what if your allocator decided to index their position in News on 22 March 2000, and just give you 83% of your money? By the end of 2000, some nine months later, News shares were down 47% against an index down a mere 3.7%.

Of course, News Corp in 1999/2000 was a much more volatile conveyance than Commonwealth Bank simply because of the prevailing environment of technological change. News Corp shares have done remarkably well over a 25-year period, but mainly thanks to a company in which they purchased a mere $2 million stake in February 2001 – REA Group (then realestate.com). So does it make any sense to lock in 12% of your Australian equities exposure to a $300 billion bank or 25% of your equity exposure to a sector experiencing virtually no forward profit growth despite minimal current impost from bad debts, and where inflation is one of the sector’s worse enemies? I think not. Given funds like Australian Super holding 25% of their balanced option in Australian shares, locking 3% of the entire fund into Commonwealth Bank shares seems to me like storing up future difficulty.

Andrew Brown is founder and principal of East 72, and manager of East 72 Dynasty Trust, a wholesale global equity fund, exclusively investing companies with controlling shareholders such as multi-generational families, management or other corporations. This article contains general information only; it does not purport to provide recommendations or advice or opinions in relation to specific investments or securities. It has been prepared without taking account of any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs and because of that, any person should take relevant advice before acting on the commentary.

[1] “Fundies could face fee threat if super funds rethink equities mandates” Joyce Moullakis

[2] Data as at 18 July 2025 sourced from tikr.com (CBA A$182.46; JPM US$291.27)

[3] The ASX indices became co-branded with S&P at end March 2000 and had float adjustments applied from that time onwards.

[4] Original data - not adjusted for subsequent splits/spins

[5] “Themes for the market” (Don Stammer) AFR 10 March 2000