From 1 January 2017 the asset test taper rate for the aged pension will increase from $1.50 to $3.00 per fortnight for every $1,000 in assets held above the threshold. This has led to some rather dubious analysis and advice suggesting that clients may be better off getting rid of their assets to maximise their age pension entitlement.

The reasoning goes along the following lines:

- if a retiree’s assets exceed the new threshold by $100,000, their age pension will be reduced by $300 per fortnight or by $7,800 per annum

- so for a retiree to be better off, they need a return of at least 7.8% on the $100,000

- if they can’t achieve a return of 7.8%+, then they are better off placing that $100,000 outside of the asset test. They can do this by spending it on renovating the family home, a holiday, pre-paying funeral expenses or gifting the money to children and grandchildren (within the permitted limits).

The ability to draw from capital

This analysis, and the advice flowing from it, is questionable as it ignores the impact on the retiree’s annual ‘income’ from drawing down their capital. The goal of a retirement income strategy should be to maximise the retiree’s sources of cashflow over time. This can be achieved by drawing down savings in combination with a part pension rather than exhausting savings to be eligible for the full pension.

We can compare two scenarios. The first scenario is where a retiree spends the $100,000 (such as on a house) to reduce their assets and be eligible for the full age pension. In the second scenario, they keep the $100,000 invested, drawing down $15,000 each year until the amount is exhausted. For simplicity, this example ignores any drawdown of assets held below the asset test threshold levels.

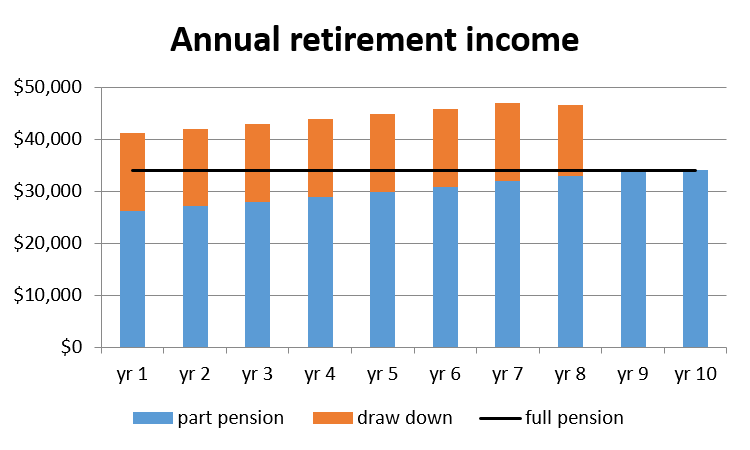

The following chart compares both scenarios. The first scenario (spending the $100,000 immediately) is shown by the straight black line on the chart. This is the full age pension for a couple of approximately $34,000 per annum (there may also be energy supplements which boost this amount). This is in current dollar terms so the amount does not change over time with inflation.

The second scenario (drawing down the $100,000 over time) is shown by the columns on the chart. The blue section of the column is the part pension that the retirees receive after the reductions for the asset test (note for couple home-owners the income test will only have a greater impact on the pension once assets above the threshold level fall below about $27,000). The red section of the column is the additional income the couple receive each year by drawing down $15,000 from their savings. Assuming an investment return of inflation + 4% per annum, the $100,000 capital not spent on the house provides an income stream of $15,000 per annum for seven years and in year eight the couple can draw down about $13,500.

Not spending on the family home provides higher income

Drawing down their $100,000 as an 'income' stream of $15,000 per annum will, in combination with a part pension, provide a materially higher annual income and standard of living compared with spending their $100,000 in year 1 to maximise their entitlement to the age pension. Of course, the family home has not benefitted from the $100,000 capital spent on it, but nobody knows how much that will improve its value (which may well go to the beneficiaries of the estate in any case).

The faulty reasoning involved in spending the $100,000 in year 1 is a classic example of mental accounting bias. This bias places a different value on a dollar of income and a dollar of accumulated capital in being able to support a retirees’ lifestyle. In this example the retirees have placed a greater value on the ability to access an additional $7,800 in aged pension in year 1, over the $15,000 in additional 'income' from drawing down their accumulated savings.

Gordon Thompson CFA is Senior Manager, Platforms, at Perpetual. This article is general information and does not consider the needs of any individual.