For many years there has been considerable media debate about the fairness (or otherwise) of the superannuation tax concessions and the apparent advantage they provide to high income earners.

However, government support for retirement income comes from two main sources:

- the direct age pension payments made by the government to many older Australians who have experienced low-moderate lifetime earnings, and

- the superannuation tax concessions, in respect of concessional contributions (received during one’s working years) and investment earnings (received both before and after retirement).

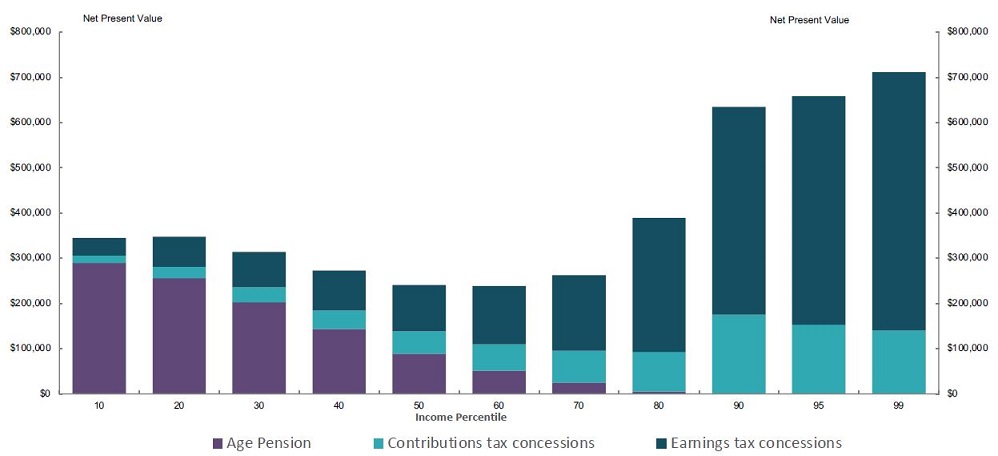

This is illustrated in the following graph taken from the Treasury consultation paper prepared for the Retirement Income Review which shows the level of lifetime government support at various income levels.

As expected, the value of the expected age pension payments reduce as incomes rise whereas the reverse applies in respect of the super tax concessions. This is chart is commonly used to demonstrate the inequity of superannuation concessions.

Government support for retirement incomes

Discounting to a present value requires assumptions

Of course, both the age pension payments and tax concessions are spread over several decades into the future. Therefore, to obtain a present value of the level of lifetime support in today’s dollars, it is necessary to discount these future payments and concessions.

The Treasury calculations discount these future levels of support at the assumed nominal GDP growth rate, or about 5% per annum. While this rate may be reasonable from the government’s perspective, as it allows for productivity gains and population growth, it is totally inappropriate when comparing the level of government support between individuals.

A lower rate relevant to individuals is needed.

The Retirement Income Review used the assumed wages growth of 4% pa until retirement and then the assumed inflation rate of 2.5% pa during the retirement years. So, to keep it simple, let’s use 3.5% pa. The results are shown below.

As expected, the present value of all these future payments increases when a lower discount rate is used. However, given that the age pension payments are further into the future than the superannuation tax concessions, the level of retirement income support received at lower incomes increases by a higher percentage than at higher incomes.

(For an analogy, growth stocks that are estimated to earn profits far into the future become more valuable when rates are lower, as the discount rate on the earnings is less. So important is this assumption that it has driven the value of growth stocks ever higher as rates have fallen over recent years).

A highly-different result

Indeed, the lowest three income deciles now receive more government support than the 80th income percentile. This is a very different result from the Treasury numbers.

It is also apparent that middle income earners receive less support than both high and low income earners. That is, there is a 'U-shape' in the level of government support.

One way of providing a fairer outcome is to reduce the assets test taper from $3 per fortnight (equivalent to 7.8%) to $1.50 per fortnight (or 3.9%). The next graph shows the effects of applying the lower deeming rates that applied in 2020 and halving the assets test taper.

While the reduced deeming rates provide some improvement, the halving of the assets test taper provides a significant boost to the level of government support to middle income earners as more age pension payments will be received by these individuals.

In fact, this is a similar result to that shown in the Final Report of the Retirement Income Review through their somewhat unrealistic assumption that retirees could spend their assets down more quickly than normal and so receive increased age pension payments.

One final comment

Even with the halving of the assets test taper, the highest income decile receives the highest level of government support due to their high levels of superannuation and the resulting tax concessions.

However, the approach adopted by Treasury in valuing these concessions is misleading as it assumes that these individuals would pay the highest marginal tax rate on their investment earnings if there was no superannuation. This is unrealistic as I’m sure they would find other legal means to reduce their tax.

In summary, the level of government support for retirement income across different income levels is not as unequal as often claimed. Indeed, if the assets test taper were halved, the level of support would be remarkably level across all incomes.

Dr David Knox is a Senior Partner at Mercer. See www.mercer.com.au. This article is general information and not investment advice.