Fees are firmly in focus and quite rightly so. Regulators, the media and asset owners are more fee-aware than ever. But in their desire to compare headline fees across products, investors risk missing the bigger picture. A single-minded focus on headline fees comes at the expense of finding true value for money as well as measuring and managing hidden costs that impact fund performance.

The investment universe is heterogeneous and no two products are exactly the same. All investments need to be assessed and considered independently. Investors need to ask themselves five key questions to establish if they are getting value for money:

- How large are fees as a proportion of added value?

- How accessible is the asset class?

- How much is the manager doing for the fee?

- What is in the fee small print?

- How do I understand and measure the hidden costs?

1. Fees as a proportion of added value

Fees should be proportionate to the amount of active risk taken, i.e. the extent a manager’s portfolio deviates from that of its respective benchmark. Assuming the manager has skill, greater active risk gives greater active return (sometimes called ‘alpha’) above a passive portfolio following the same benchmark. Therefore, asset owners are able to invest less capital to achieve a given level of alpha since the manager is making more active decisions. This should be compensated with a higher fee, all else being equal. Conversely, closet index trackers delivering a low level of alpha should be paid close to passive fees.

Many active managers add value through their largest overweight (highest conviction) positions, only for this to be eroded by a large tail of smaller holdings they have little or no conviction in. The large number of smaller holdings keep the manager’s tracking error down, but at the expense of offsetting the alpha. By focusing an equity mandate on, say, 10-20 stocks, investors get a concentrated portfolio of best ideas. It is then possible to build a diverse, highly-active portfolio of concentrated managers which has similar systematic and sector risk exposures as the benchmark.

2. Hard to access assets

Manager fees should be higher when the cost of doing business is greater. A good example of this is direct lending, where the manager organises and contracts on each deal rather than simply buying pre-packaged units from an exchange. Typically, strategies such as direct lending have no low-cost or passive alternatives and are often hard to transact, so investors should expect to yield an illiquidity premium.

3. How much is the manager doing?

Managers can add value over and above active risk through more 'management' of a fund, such as stewardship, activism through private equity and varying gross and net exposures.

Stewardship can add significant value: a CEO’s remuneration package, for example, can be larger than the fee paid to the asset manager, yet few managers vote against CEO pay.

Then there is private equity: firms operating private equity strategies contend with M&A costs, debt fees, placement fees, as well as board and consultancy fees. These can be a significant part of the private equity manager’s fee, yet these costs are also paid in public equity mandates where they are hidden in the companies’ profit and loss accounts.

Investors might also pay for products that provide more exposure to alpha or higher gross exposure.

4. Check the small print

The way managers calculate and accrue fees can also make a big difference. Even if the headline fees are the same, a performance fee with a high watermark and hurdle will align managers and investors much better than those without either of these mechanisms.

5. Measuring and managing hidden costs

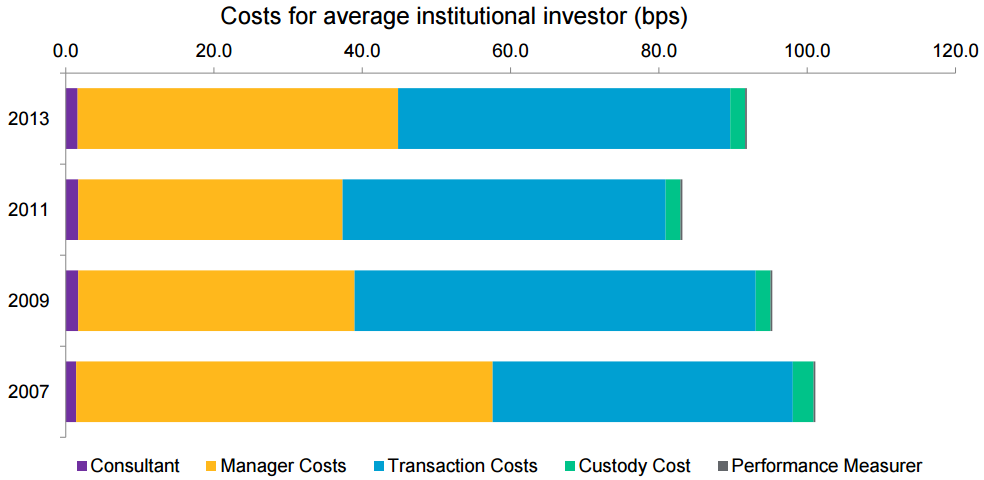

The chart below shows the total costs paid by the average institutional investor globally over time. While manager fees now represent less than half the total costs paid by institutional investors, they are still sizeable and can be reduced further. Note that transactions costs are often higher than management costs, yet there is far more focus on the latter.

Chart 1: Estimate of average costs for institutional investors, basis points per annum

One way to reduce expenses is simply transact less often, such as by encouraging long-termism. Following work done by our Thinking Ahead Group in 2003 and 2004, a number of our clients invested in long-term equity mandates. These long-term mandates have been a success from a performance perspective, with our model portfolio returning CPI+4.9% pa, or Index+2.1% pa, over the 11-year period to end-2015.

Administration fees, trading costs and expenses

There is also a huge number of hidden costs which are easy to ignore but which can have a material impact on the portfolio. They fall under the broad umbrella headings of 'administration costs' (such as custody and auditing), 'trading costs' (such as dealing commissions and foreign exchange transactions) and 'expenses', which can be just about anything.

Administration costs are the only ones that tend to be included in a given total expense ratio. It is likely, over time, that trading costs will start to be included in total cost comparisons, with an unbundling of execution and research costs driven by regulation.

Foreign exchange is another cost that few investors focus on. Many active managers have poor forex processes, with the design and execution left to back office teams which may not fully understand the 'all in' cost of the strategy.

Finally, there are expenses on items such as Bloomberg terminals, travel costs and indemnity insurance, which we believe should be part of the management fee.

Conclusion: ask questions and seek transparency

In an age where everything and everyone is under greater scrutiny, high costs are naturally raising questions about how much value the industry creates. Investors need to ask the right questions that lead to where the real costs lie and how they can then be addressed.

One way to manage cost issues is via managed accounts, or a managed-account platform, where investors pay the manager a management fee and the managed account provider controls the remaining costs – from prime brokers, to forex, to custody. This has the added benefit of full transparency for each underlying position.

[Editor's Note: There is a major debate which borders on hysteria in the UK on 'hidden costs' and transparency in asset management, as reported in this article, called, 'Lack of fee transparency a 'festering sore' for UK asset managers'. It calls into question the efficiency of the market as new disclosure requirements are debated.]

Craig Baker is Global Chief Investment Officer at Willis Towers Watson. This article is general information and does not consider the investment needs of any individual.