In Greek mythology, Scylla was a seven-headed monster that lived on one side of the Straits of Messina, a narrow strip of water separating the island of Sicily from the Italian mainland. On the other side lay Charybdis, a deadly whirlpool that led to many a watery graveyard for passing ships.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Circe advises Odysseus to sail closer to Scylla,

“A large fig tree in full leaf grows upon it, and under it lies the sucking whirlpool of Charybdis. Three times in the day does she vomit forth her waters, and three times she sucks them down again; see that you be not there when she is sucking, for if you are, Neptune himself could not save you; you must hug the Scylla side and drive ship by as fast as you can, for you had better lose six men than your whole crew.”

Modern Greece faces its own dilemma; should it too sail within reach of Scylla, the 28-headed monster that lives in Brussels to avoid Charybdis, the ‘sucking whirlpool’ that is the return of the drachma?

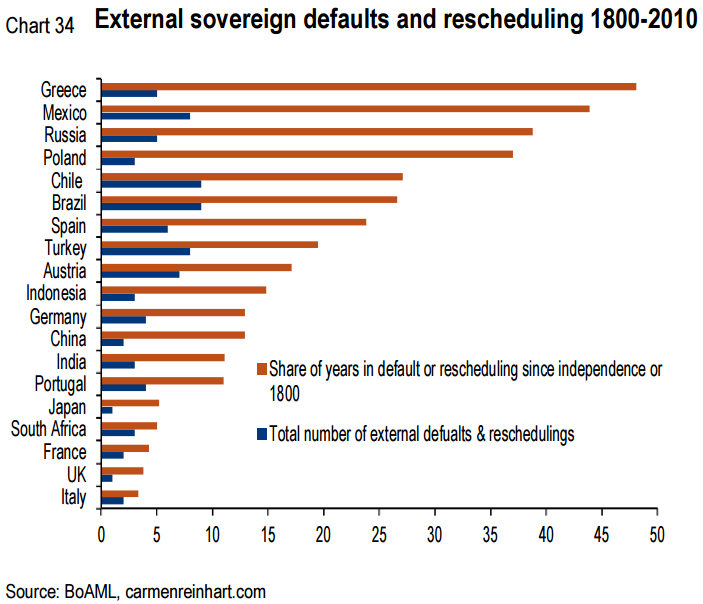

Golden Rule No. 1 in Stanford Brown’s 10 Golden Rules of Investment is Mark Twain’s prophetic comment that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme”. Greece isn’t technically in default but the probability of it being able to repay its 340 billion euro debt load is zero. This is actually not an unusual situation for Greece as it has been in default for 48 of the past 210 years.

The Greek Parliament has recently passed a much harsher austerity Budget than was rejected by its own people in a recent referendum. Prime Minister, Mr. Tsipras, elected to end austerity, has bizarrely agreed to a tightening of the austerity noose. Greece, reeling under the weight of its burgeoning debt mountain, has been given an additional 86 billion euros in debt. The IMF has said it won’t participate as it believes it has no chance of ever getting repaid. And the Greek people want to stay in the euro, but reject the austerity that membership requires. In this topsy-turvy world of contradictions, catch-22s and nonsense, the Mad Hatter could not have put it any better,

“If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn't. And contrariwise, what is, it wouldn't be. And what it wouldn't be, it would. You see?”

Pour encourager les autres

David Zervos, chief strategist at research house, Jeffries, never doubted the outcome,

“The Greeks now stand as poster children for European profligacy. And they are being paraded through every town in the EU, in shackles, as the bell tolls near the gallows for their leader… The Portuguese, the Italians, and Spanish are surely taking notice… With no real way to ensure fiscal discipline through the treaty, they resorted to killing one of their own in order to keep the masses in line.”

There has always been widespread support in Europe for the Union, but the single currency has never been popular. The euro was the price demanded by France for the re-unification of Germany in 1990; such was their fear of a strong neighbour to the east. The French believed that binding Germany into the corset of monetary union would curb her power. What a colossal mistake.

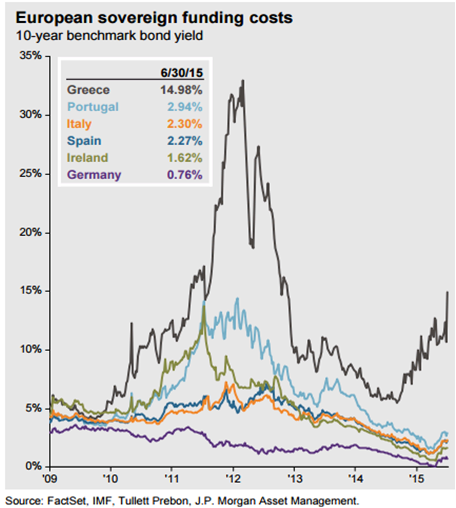

Whilst tragic for Greece, the fallout for investors across the globe is not going to resemble a ‘Lehman moment’ – even in the worst case of a messy Greek exit from the single currency. There are four key reasons for our complacency. First, Greece is very small, accounting for just 0.25% of the global economy; the European banking system is now much less exposed to a Greek default, having swapped its Greek debt with the IMF and the Eurozone; the other vulnerable European economies of Portugal, Spain, Italy and Ireland are in much better economic shape than during the last Eurozone sovereign debt crisis in 2011; and finally, Europe has now established robust defence mechanisms with sufficient firepower to handle future crises. These include a bailout fund called the European Stability Mechanism (despite being expressly banned by the Maastricht Treaty), cheap funding for banks from the European Central Bank, and the ECB’s mammoth Quantitative Easing program, which has so far contained any rise in bond yields of the peripheral countries (see chart below).

The disastrous experiment that was the European Single Currency will serve as a classic case study for generations of future Business School graduates. The lesson learnt is that economics always trumps politics, no matter how hard you wish it wasn’t so. If only we had all listened to the great economist, Milton Friedman, who in 1997, two years prior to the establishment of the single currency, had this to say,

“The drive for the Euro has been motivated by politics not economics. The aim has been to link Germany and France so closely as to make a future European war impossible, and to set the stage for afederal United States of Europe. I believe that adoption of the Euro would have the opposite effect. It would exacerbate political tensions by converting divergent shocks that could have been readily accommodated by exchange rate changes into divisive political issues. Political unity can pave the way for monetary unity. Monetary unity imposed under unfavorable conditions will prove a barrier to the achievement of political unity.”

The image at the start of this article depicts Greece sailing within reach of Scylla (the euro), to avoid Charybdis, the ‘sucking whirlpool’ that is Grexit. But have we mixed our monsters? Returning to the drachma would give Greek businesses an immediate competitive boost, albeit with much associated turmoil, and buy the country precious time to make necessary reforms. Perhaps Grexit is the modern-day Scylla, resulting in the loss of six years, whilst the whirlpool of Charybdis represents the continued membership of the European single currency and a lost generation. In this case, it’s better the devil you don’t know.

Jonathan Hoyle is Chief Executive Officer at Stanford Brown. Any advice contained in this article is general advice only and does not take into consideration the reader’s personal circumstances.