Why would investors earn less than the funds they invest in? It all comes down to timing.

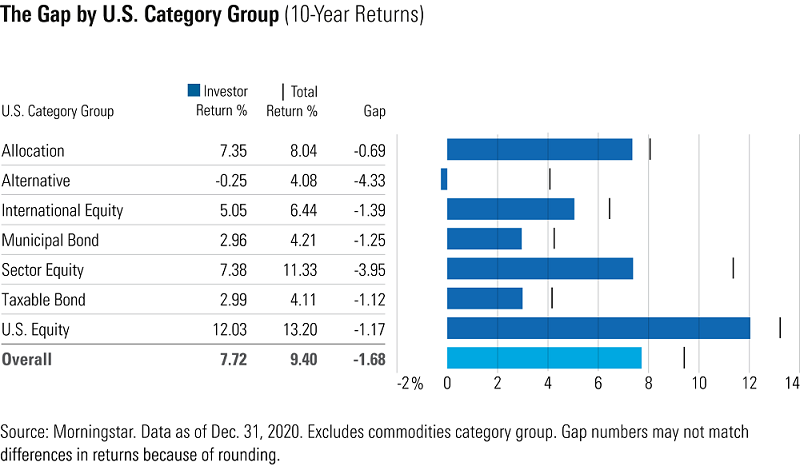

Our '2021 Mind the Gap' study of dollar-weighted returns finds investors earned about 7.7% per year on the average dollar they invested in equity funds over the 10 years ended 31 December 2020. This was about 1.7% less than the total returns their fund investments generated over that time span.

This shortfall, or ‘gap’, stems from inopportunely-timed investment in and redemptions from funds, which cost investors nearly one-sixth the return they would have earned if they had simply bought and held.

The persistent gap makes cash flow timing one of the most significant factors – along with investment costs and tax efficiency – that can influence an investor's end results.

What is the gap between investor returns and total returns?

To use a simple example, let's say an investor puts $1,000 into a fund at the beginning of each year. That fund earns a 10% return the first year, a 10% return the second year, and then suffers a 10% loss in the third year, for a 2.9% annual return over the full three-year period. But the investor's dollar-weighted return in this simple example is negative 0.4%, because there was less money in the fund during the first two years of positive returns and more money exposed to the loss during the third year. In this case, there was a 3.3% per annum gap between the investor's return (negative 0.4%) and the fund's (2.9%).

In our study, we estimate the gap between investors' dollar-weighted returns and funds' total returns in the aggregate. This allows us to assess how large the gap is and how it's changed over time.

The results by different fund types

More specialised areas with the most volatile cash flows - namely, alternative funds and sector equity funds - fared much worse than average and pulled down the aggregate results. The more mainstream areas that are home to the majority of investor assets such as broad equity and bond funds fared much better, with return gaps of about 1% per year.

In this US study, equity fund investors experienced a 1.2% annual gap while bond fund investors suffered a 1.1% gap per year.

A few other areas worth noting:

- Asset allocation funds had the smallest gap, suggesting that their built-in asset-class diversification makes them easier for investors to buy and hold over time. Investors in these funds, which combine stocks, bonds, and other asset classes, experienced a dollar-weighted return lag of only 0.69% per year over the 10 years.

- Alternative funds have proved difficult for investors to use successfully. The average dollar invested in these funds lost about 0.3% annually over the 10 years, which was a remarkable 12% per year less than the returns in US equity funds.

- Sector-specific equity funds also saw negative gaps for investors, by about 4% per year. These specialised funds were doubly disappointing, with returns lagging diversified equity funds and investors failing to capture the full benefit of those lower returns.

How does dollar-cost averaging impact investor returns?

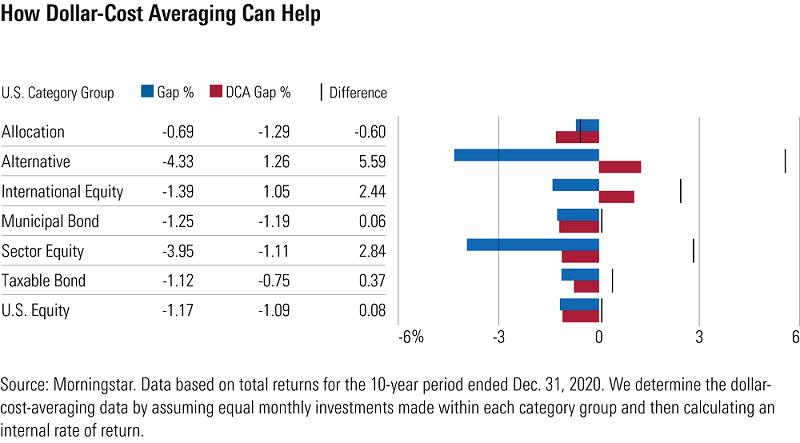

We also added a series of returns to see how the results would look in a hypothetical scenario in which an investor contributed equal monthly investments (dollar-cost averaging) to funds in each broad category group.

Dollar-cost averaging doesn't usually lead to better results compared with a buy-and-hold approach. In fact, because market returns are often positive, dollar-cost averaging often leads to lower investor returns.

This simply reflects the underlying maths of total returns: If returns are generally positive, investors are typically better off making a lump-sum investment and holding it for the entire period. Investors who contribute smaller amounts over time often have fewer dollars invested during periods with strong returns.

The results show dollar-cost averaging can help investors avoid some of the ill effects of poorly-timed cash flows by enforcing a more disciplined approach. In fact, following such a systematic investment approach would have improved investors' returns in six of the seven major category groups. With international-equity and sector-equity funds, for example, investor returns based on dollar-cost averaging came out more than 2% per year ahead of investors' actual returns.

What to do to improve investor returns

The persistent gap between investors' actual results and reported total returns may seems disheartening, but investors can take away a few key lessons about how to improve their results. The study's results suggest:

- Keep things simple and stick with plain-vanilla, broadly diversified funds.

- Automate routine tasks such as setting asset-allocation targets and periodically rebalancing.

- Avoid narrowly-focused funds for long-term investing, as well as those with higher volatility.

- Embrace techniques that put investment decisions on autopilot, such as dollar-cost averaging.

These findings shine more light on the merits of keeping things simple. In particular, funds that offer built-in asset class diversification, such as balanced funds, help investors keep more of their returns.

Finally, we found that investors' trading activity is often counterproductive. Investors can improve their results by setting an investment plan and sticking with it for the long term. Investors who follow a consistent investment approach and avoid chasing performance will likely reap rewards over time.

Amy C. Arnott, CFA, is a Portfolio Strategist for Morningstar.

For more details on the results and methodology, see the 2021 Mind the Gap Report. We changed the way we calculate the total returns used as benchmarks for the gap numbers in this year's study. In past studies, we used an equally-weighted average but this year we used an asset-weighted methodology to calculate the average. This change had the effect of increasing the average total return figures used as a benchmark for the gap calculations, leading to a wider return gap overall. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. It has been edited somewhat from the original US version for an Australian audience.

Register for a free trial of Morningstar Premium on the link below, including the portfolio management service, Sharesight.

Try Morningstar Premium for free