It is well known that there are both benefits and costs to living and working in the city – higher wages on the one hand, and higher housing costs on the other. In this article, we refer to the higher wages in the cities relative to the regions as the urban wage premium and the higher housing costs in the cities relative to the regions as the urban housing cost premium.

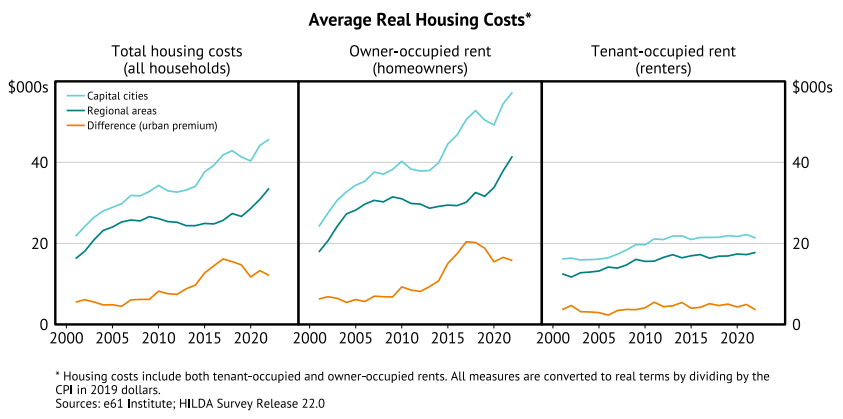

Using the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, we find that, on average, housing costs – measured as the sum of both tenant-occupied rents and owner-occupied rents – are rising faster in the cities than in the regions.

The urban housing cost premium is increasing because of a widening gap in housing prices as measured by owner-occupied rents. Rising housing costs have been a strong feature of the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets.

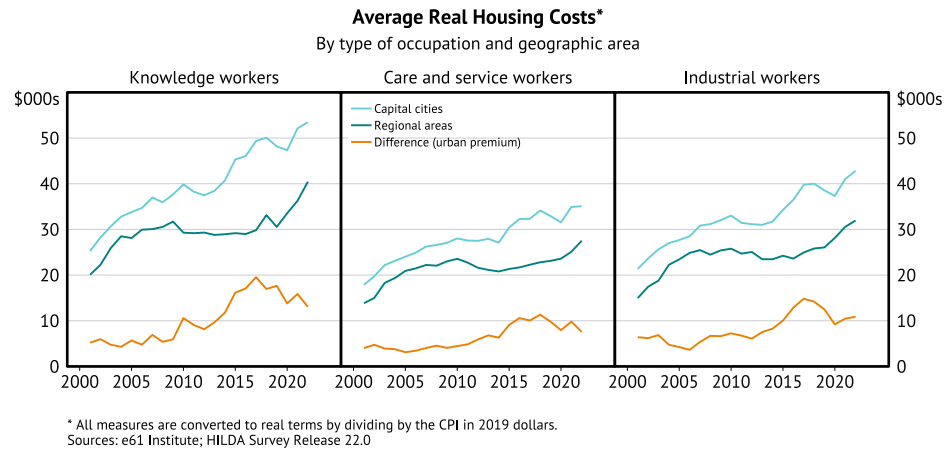

A novel feature of the housing cost estimates from the HILDA Survey is that we can track how housing costs are changing for workers in different occupations and geographic regions.

The estimates indicate that housing costs have risen by more for city-based workers compared to regional workers across all occupations since the mid-2000s. This increase in housing costs is mostly driven by higher costs of home ownership, as measured by owner-occupier rents.

Why are housing costs rising more in the city than in the regions?

It is difficult to isolate a specific cause. Housing costs are determined by locational trends in supply and demand – with that demand also determined by relative earnings opportunities in different locations. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that housing supply has not kept up with rising housing demand in these locations.

A further possibility is that, in areas where housing supply is most constrained, immigration has contributed to housing demand, alongside other sources of demand.

Sydney and Melbourne remain the destinations of choice for many immigrants, which has brought many economic and cultural benefits to the cities. Over half of Australia’s foreign-born population lives in Sydney and Melbourne.

Regional areas, which typically find it easier to expand housing supply, do not have a high share of immigrants despite in-built incentives in the immigration system.

Without a corresponding increase in housing supply, stronger demand for housing in the cities may be contributing to higher housing prices. And, given the low shares of immigrants moving to the regions, they have not experienced the same housing demand increase. Higher wages and housing costs tend to interact.

Whatever the underlying causes, a given individual weighs up locational decisions based on relative housing costs and wage prospects between locations. To the extent that housing costs have risen faster than wages for many workers, this is likely to influence their decisions about where to locate.

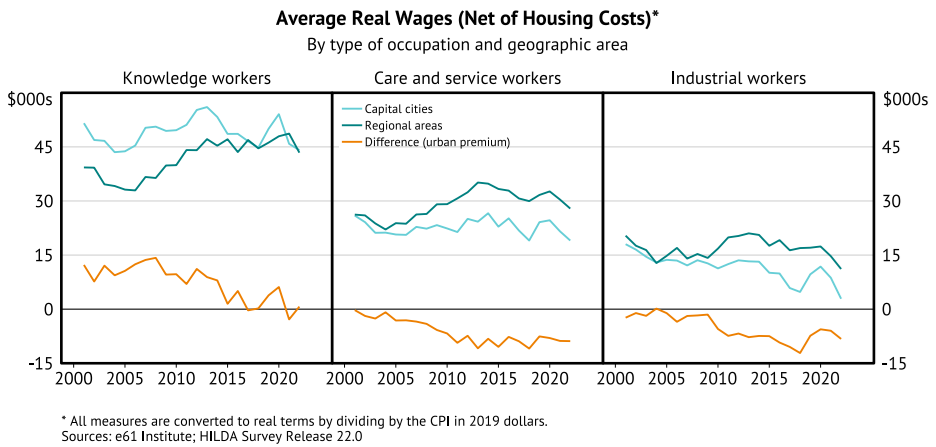

Broadly speaking, in the early 2000s the benefit of living in capital cities – as measured via wages – outweighed the cost – as measured by housing. But that is no longer the case.

Unsurprisingly, given we have found that industrial workers no longer obtain a wage benefit from being in the city, their urban housing cost premium exceeds their urban wage premium – and that has been the case since the start of this century.

Similarly, for city-based care and service workers, their wage premium has fallen short of their housing premium for some time too. But, most strikingly, this phenomenon is now extending to knowledge workers who earn the highest urban wage premium.

The locational calculus is changing for many workers

For workers, on average, the incentive to stay in, or move to, the city has been weakening. The urban wage premium is no longer sufficient to offset the housing cost premium associated with living in the city.

This average effect does not apply to every individual – many workers have above-average urban wage premiums. Many incumbent city-dwellers have accumulated significant equity in their homes, such that the current urban housing cost premium could be less likely to affect their locational choices.

Hence, a change in the urban wage premium and a rise in the urban housing cost premium may not matter to the same extent for all.

For some, the benefits of city living are more than just wages, including access to a higher share of cafes, bars and restaurants and educational opportunities, as well as proximity to family and established community networks. On the other hand, those seeking to purchase a home for the first time, face a pivotal locational decision. For them, the shift in relative wage and housing cost premiums could prove more decisive.

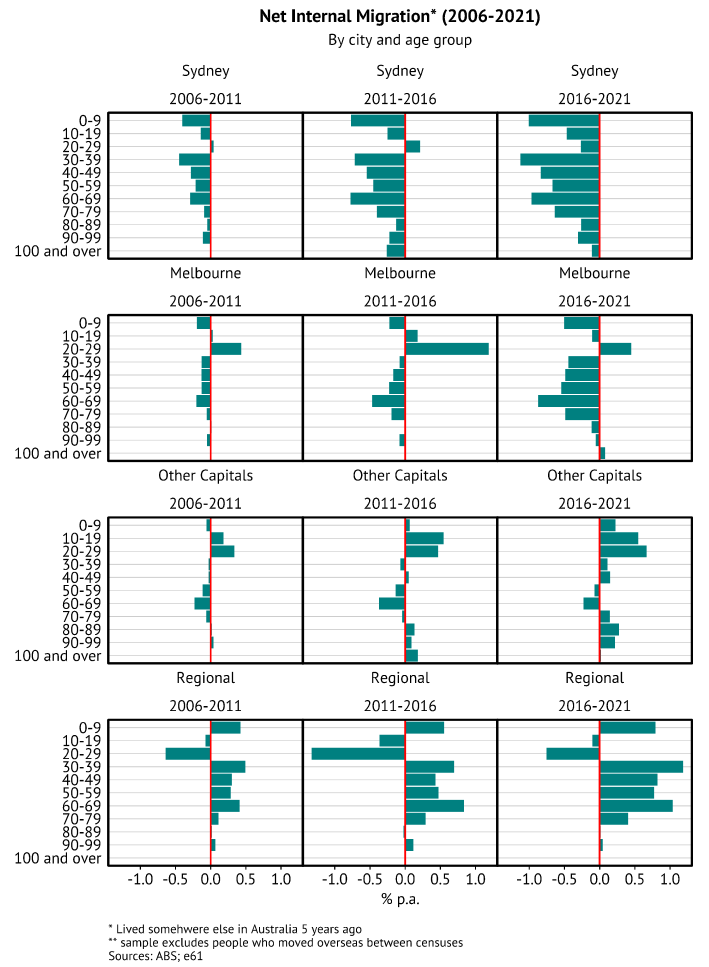

The combination of rising relative housing costs and flat-to-falling relative wages in the cities may explain why people in their 30s are leaving Sydney and, to a lesser extent, Melbourne. This exodus has been particularly strong for those in industrial, care, and service jobs.

Millennials in Sydney are most impacted

Sydney and Melbourne are experiencing outflows of people to other parts of Australia – with more people leaving than coming, excluding overseas immigrants.

In Melbourne, since 2006, people of all age groups have been leaving the city, with 20-year-olds the exception – they are the only age group entering on net. In Sydney, the outflows are stronger and those in their 30s are leaving at the highest rates.

The fact that those in their 30s are leaving reinforces the idea that rising housing costs are a key factor in their location decision. People in this age bracket will be making life decisions, such as getting married and having children, which are typically associated with demand for larger homes.

Where are they going?

For Melbourne, people are more likely to move to the outer suburbs than leave Victoria entirely. For Sydney, some people are moving to coastal regions like the Central Coast and Wollongong, while others are leaving the state altogether.

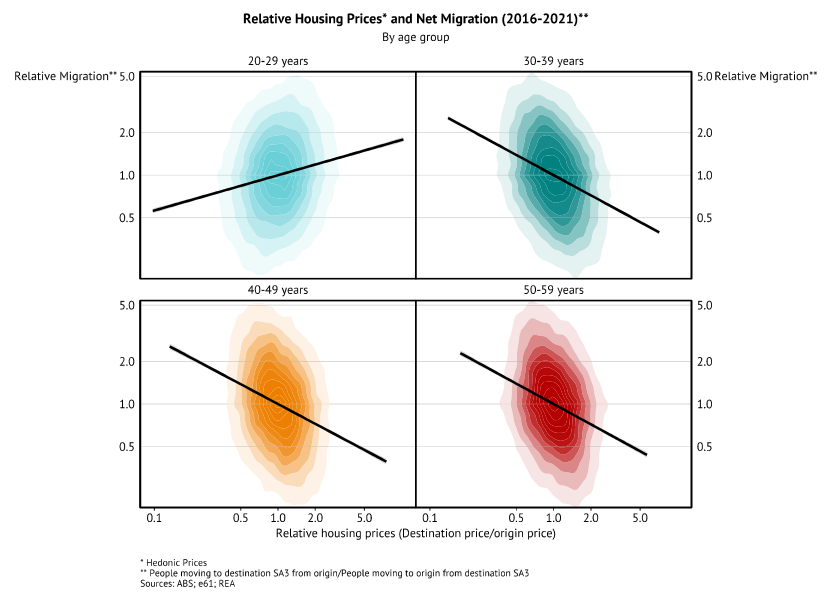

People who are 30 years and older are moving away from high housing price areas to low housing price areas, suggesting they are seeking home ownership. This is not a new behaviour – but the link has become stronger as housing prices have risen over time.

By contrast, people in their 20s – who are more likely to be renters than buyers – are moving towards areas with more expensive housing. This holds true regardless of labour market status. Those in their 20s may still be choosing to live in the cities to gain better educational opportunities and access amenities.

We note three major economic implications from the above: risk of labour misallocation, cities becoming less occupational diverse, and an opportunity for Australia’s regions.

Risk of labour misallocation

Productivity and real income growth have slowed over recent decades. This report raises the possibility that, for some young people, the housing cost premium in cities could be a decisive motivation for moving – causing them to move away from areas of high wages and productivity, and potentially high human capital investment.

To the extent that constraints on the supply of housing in the cities are raising the cost of housing and preventing workers from moving to locations that maximise their productivity, this will lead to a misallocation of Australia’s workforce.

Less occupationally diverse cities

The trajectory of wage and housing premia is such that industrial and care workers have faced the strongest incentives to locate away from cities. A key question is whether this could lead, over the long term, to greater occupational segregation across locations: with highly qualified knowledge workers located in the cities and industrial and care and service workers in regions.

Complete segregation is impractical – there will be demand for the services of industrial and care and service workers in the city. Hence, wages could adjust to attract them.

Opportunity for Australia’s regions

The movement of some city-based workers into the regions could also represent an opportunity for the regions. Workers who leave the city tend to earn more than their new neighbours who are in the regions and bring with them city-based skill accumulation.

In addition, the regions have the potential to continue to attract and retain more city-based workers. But it will be important that regional housing supply can adjust, to accommodate the additional demand without upward pressure on housing costs that could create inequality within regions.

This article is an abridged excerpt from the e61 institute’s research paper titled “The Lucky Country or the Lucky City?”. You can read the full report here. Contributors include Michael Brennan, Elyse Dwyer, Nick Garvin, Theo Gibbons, Rose Khattar, Gianni La Cava, Aaron Wong.