Private equity is not an asset class at the top of most individual investors’ wish lists. Why? It is certainly an asset class people are aware of. It gets a lot of press, and it is an asset class that large institutional investors value and allocate to. The Future Fund, for example, has a 15% allocation to private equity.

So why don’t individual investors invest significantly in this asset class? The overriding theme is that it is too hard to access. Reasons may include a lack of suitable investment vehicles which would enable investors to obtain meaningful and diversified access. The investment process is also complicated by minimum equity commitments, the management of progressive drawdowns, irregular distributions, and long-term lock ups.

What is private equity?

Private equity typically involves taking an ownership interest in an unlisted, private business or asset. It includes a broad range of longer-term and company-specific exposures which, because they are not listed on a public market, tend to exhibit somewhat lower correlation to traditional stock and bond markets. Private equity managers seek to generate superior returns through taking an active role in monitoring and advising companies through restructuring, refocusing and revitalising tactics in order to sell the investment at a profit. It is a more hands-on investment compared to an investment in the shares of a listed company.

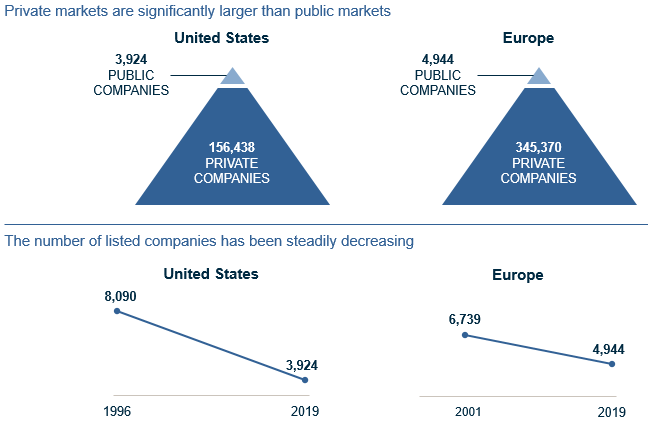

It may surprise some that the universe of private companies is significantly larger than that of public companies, and that the number of listed companies has been steadily decreasing. As shown in the following diagrams, since 1996 the number of US listed companies has fallen 50%.

Source: S&P Capital IQ

Global allocations by investors to private equity have been steadily growing since 2000, having increased almost 6 times over the period.

How has private equity performed?

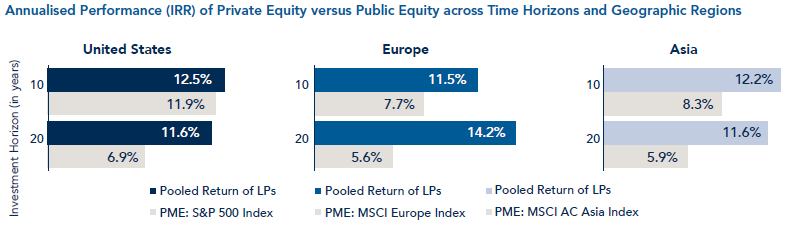

One of the key reasons for the increasing allocations to private equity may have been its performance. Private equity has outperformed public equity across long term time horizons (10 and 20 years) as well as geographic regions. The following graphs compare private equity investments against hypothetical funds that buy and sell shares of the relevant equity index at the same time the private equity vehicles call and distribute cash.

Source: GCM, using data from Burgiss Group and MSCI

There are a number of factors that have historically contributed to the strong performance of private versus public equity. The most significant are:

- the lack of short-term public pressure allowing for a long-term investment orientation

- the historical resilience of performance across various market environments

- the illiquidity premium – investors prefer liquid investments and therefore demand an increased return on less liquid alternatives.

Five ways the risks are different from listed equity

The unlisted and hands-on nature of private equity investments suggest there are different risk considerations compared to public equity markets. Some risks are of course the same – economic, market, currency, political, etc. – but others differ, and we highlight these below:

- Unlisted private equity investments are typically illiquid. Private equity funds may hold securities or other assets in companies that are thinly traded or for which no market exists.

- Distributions tend to be irregular and depend on the sale of an underlying investment.

- Third party pricing information is also not available for a large proportion of private equity assets. Valuations may therefore require discretionary determinations and in certain circumstances investors may have to rely on valuations from the underlying managers themselves.

- The companies invested in may involve a high degree of business and financial risk. They may be in the early stage of development, may be rapidly changing, may require additional capital to support their operations, or may be in a weak financial condition. While these are also opportunities, they clearly represent risks that need to be controlled by private equity managers.

- There is also generally less information available about private companies than their listed peers. This means that investors with higher quality information are often able to make better investment decisions and is one of the reasons performance dispersion in private equity tends to be greater than in the public markets. Extensive due diligence and careful monitoring are essential safeguards when constructing private equity portfolios.

What does private equity bring to a diversified portfolio?

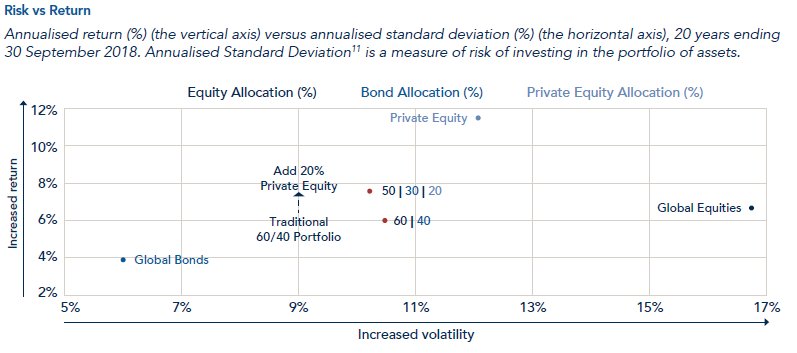

Historically, one of the key benefits of private equity has been its somewhat lower correlation to other traditional assets and the diversification benefits this has provided at a portfolio level. The chart below shows that adding a 20% allocation of private equity to a traditional 60/40 equities/bond portfolio generated higher returns with lower risk (as measured by volatility) over the last 20 years.

Source: GCM using data from Burgiss Group

To an extent, the diversification may be derived from periods of economic stress such as the GFC.

How can retail investors access private equity?

Private equity has been a difficult asset class to access for individual investors. However, there are now a handful of unlisted and listed funds and trusts in Australia that overcome many of the hurdles.

Listed and unlisted vehicles have their own pros and cons, but the key is liquidity. Unlisted funds may offer daily or monthly liquidity, however, given the illiquid nature of the underlying investments, they have the ability to restrict or freeze redemptions. Listed vehicles provide liquidity for investors who can buy and sell on market as long as an active market exists.

The private equity universe is vast, differentiated by types of companies, investment strategies, and implementation options. Private investment vehicles differ markedly across these variables and, as with listed equity vehicles, it makes sense to have more than one in your portfolio.

Nick Griffiths is the Chief Investment Officer of Pengana Capital. This article is for general purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.