The phrase ‘secular stagnation’ is again popping up in reports and discussions on the global investment outlook. Secular stagnation – persistently weak economic growth - can result from a sustained deficiency of demand, continuing low growth in productivity, or from a slowly growing or shrinking workforce. One of its consequences, over the medium-term and longer, is that investment returns are very low, even negative.

In my view, secular stagnation is unlikely in countries like the US and Australia. However, with populations ageing and with enthusiasm for productivity-boosting reforms waning, both countries are likely to experience, over the medium-term and longer, modest reductions in potential growth rates and in average investment returns. Japan has experienced a couple of decades of secular stagnation and the euro-zone is now at serious risk of a similar experience.

Concerns about secular stagnation come and go

The concept of secular stagflation was developed by Alvin Hansen, a US professor of economics, during the Great Depression and soon after the publication of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by John Maynard Keynes.

Hansen postulated that capitalist economies would suffer both a sustained glut of saving and limited opportunities to invest. As a result, the ‘natural’ rate of interest (the interest rate level that would balance saving and investment at full employment) would be significantly negative – and well beyond the ability of central banks to deliver.

The outbreak of the Second World War caused attention to switch to other, more immediate matters, and both the allied and axis powers undertook massive increases in military spending that had war-time economies operating at full capacity. Almost as soon as peace returned, concerns developed about economies and investments falling into the grip of secular stagnation – now renamed the ‘under-consumption theory’. As things turned out, however, the 1950s and 1960s were the decades of postwar prosperity, and most economies operated close to their potential output levels. Interest in secular stagflation fell away.

The oil price shocks of the 1970s led to a revival of fears about secular stagnation – re-badged simply as ‘stagflation’. As the oil producers’ cartel weakened and central banks brought inflation under control, those fears subsided.

Fears about long-term stagnation (and with it, sustained low investment returns) have come to the fore again during and since the global financial crisis. Initially, these concerns were usually presented as part of predictions for ‘a new normal’ of very modest growth in GDP and low investment returns.

Then – and just when some people were thinking it safe to go back into the ocean - Larry Summers (former head of treasury under Bill Clinton, and also President Obama’s preferred pick as chairman of the US central bank before the position went to Janet Yellen) launched a hard-hitting campaign on the long-term risks to the US and global economies from sustained negligible growth. No old wine in new bottles for him: he uses the phrase, secular stagnation, minted almost 80 years ago.

As Summers sees it, the US economy was kept afloat, even in the decade before the global financial crisis hit, only by debt and asset bubbles. He foresees a lasting glut of saving in the US, Asia and the Middle East – at a time when opportunities to invest and to raise productivity in western countries are limited and when an ageing population will be constraining growth in the US workforce. This combination of events will “reduce normal levels of interest rates…(and) we’re getting financial bubbles before we get full employment”.

Fears of secular stagnation and economic policy in the US

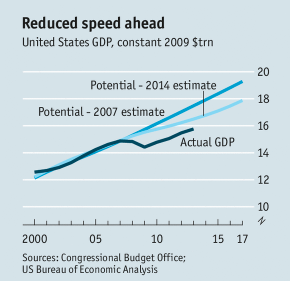

This graph, from The Economist, illustrates the thinking of the US Congressional Budget Office on the secular stagnation debate in the US: that the trend rate of potential growth has been lowered by the reluctance to invest and the abundance of saving, but only modestly; and the current under-performance of the US economy is mainly cyclical in nature and will correct.

Senior officials at the Fed share this view: expectations are that the trend rate of potential growth in the US is reducing but without secular stagnation being a likely outcome. They expect the labour force participation rate, which has fallen sharply in recent years, to experience a powerful cyclical increase.

How big a risk is secular stagnation?

In my view, the risk of secular stagnation is being exaggerated, particularly for countries such as the US and Australia, though both economies seem likely to experience some slowing in trend rates of economic growth, and somewhat lower average returns from investments, as populations age and productivity gains prove hard to come by.

Japan’s two wasted decades show, among other things, that a failure to reform and re-capitalise banks is a major contributor to secular stagnation – a lesson that the euro-zone countries need to learn from and to act on.

Fidelity’s Michael Collins offers a sensible conclusion in his review of Summers’ arguments:

“There are solutions to the prospect of secular stagnation such as sustained increases in infrastructure spending. And then there’s the possibility that Summers is overstating the case for endless stagnation.”

“The world could simply be undergoing the sluggish growth that is expected after a financial crisis. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in their book This Time is Different found that damage from a financial binge takes years to repair …”

“Summers’ likely mistake [is] he appears to be underplaying the fact that economic booms sow their own demise and recessions create their own revivals, largely through pent-up demand after time has allowed the worst excesses to be tackled … Economies have built-in mechanisms to drive economic cycles, even if those recoveries can sometimes come too slowly for many including the most articulated and respected economists.”

Don Stammer chairs QVE, is a director of IPE and an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund, Altius Asset Management, Philo Capital and Centric Wealth. The views expressed are his alone. An earlier version of these comments was published in The Australian.