Listed Investment Companies (LICs) in Australia are going through a renaissance driven by the introduction of FOFA (Future of Financial Advice) and the amendment to the Corporations Act in 2010 allowing LICs to pay dividends when deemed solvent by the board.

This article discusses these topics, the history of the LIC sector and what the future holds for the space.

A LIC is a listed equity fund: a managed share investment fund that is itself a listed share. In Australia there are 61 listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) with a value of $20.4 billion. Currently 46 of them are trading below the value of the shares they own, creating a lot of great value investing opportunities.

The first investment trust was launched in the UK in 1868 by Foreign & Colonial. It was the world’s first collective investment vehicle and planned to raise £1 million to invest in government stock of foreign countries and colonial territories. In the prospectus it said it aimed ‘to give the investor of moderate means the same advantages as the large capitalist in diminishing the risk of investing in foreign and colonial government stocks, by spreading the investment over a number of different stocks’.

Unique structure of LICs

This principle is still the same today. Like unit trusts, LICs are pooled funds invested in a diverse range of shares that are listed on a stock market. But, unlike unit trusts, LICs are incorporated as quoted companies and instead of buying units in a fund, investors buy shares in a company.

LICs are closed end funds with a fixed amount of capital. No one can buy shares in a LIC unless someone else is willing to sell. Therefore the share price moves according to the rules of supply and demand rather than as a direct reflection of the movement in the underlying assets of the LIC. Thus LICs often trade at either a premium or a discount to the value of the assets they own, namely their Net Tangible Assets (NTA).

It is this premium or discount that makes LICs appear complicated. Most investors are familiar with unit trusts, which quote their unit values every day. Investors can buy or sell the units at the stated NTA daily. With LICs, the variance between the value of the LICs assets and its share price is a complication for some, but provides an incredible opportunity for others.

In a market downturn, such as the GFC, investors in a managed fund are likely to sell their units to get cash, forcing the managed fund manager to liquidate some of their holdings to repay the unit holders. This means the manager is selling into a market that has fallen, and may be forced to sell stocks that they believe are cheap. In a bull market, when money is rapidly flowing into managed funds, the reverse is the case. The managed fund manager may be forced to buy shares they know are over-valued as money pours in from investors. This is never the case with LICs. The LIC manager can continue to hold the same portfolio, and is never forced to sell or buy any stock. Their total focus is on managing money for the benefit of all their shareholders — the manager’s investment strategy is not dictated by market sentiment or flow of funds. They may start buying in a downturn and pick up some bargains or sell stocks that become overvalued in a bull market. Supporters of LICs argue that the closed end structure enables them to invest more efficiently and outperform unit trusts or other managed funds over time.

Australian evolution and outlook

The origin of the LIC sector in Australia dates back to the 1920s. The oldest investment company that is now listed is Whitefield Ltd (WHF), which was incorporated in 1923, originally as an investor in mortgage loans. Its business has been solely focused on equity investment since 1949, though it didn’t list on the ASX until 2 August 1971.

The largest Australian LIC started life in 1928 as Were’s Investment Trust Ltd. In 1936 it changed its name to Australian Foundation Investment Trust Ltd and it adopted its present name, Australian Foundation Investment Company Ltd (AFI), in 1938. It listed on the stock market on 30 June 1962. In 1973 it was used to amalgamate the Capel Court group, which resulted in the takeover of Capel Court Investments, Breton Investments, Clonmore Investments, Haliburton Investments, Jason Investments, Jonathan Investments, National Reliance Investments and Shelbourne Investments. AFIC now has assets of $5 billion. The second-largest LIC, Argo Investments Ltd (ARG), was established in 1946 and listed on the ASX in 1950. It currently has a market cap of $4.3 billion.

The LIC sector is currently benefiting from two major structural changes.

The first is the change to the Corporations Act in June 2010, allowing companies to pay dividends as long as they are solvent. Previously they could only pay a dividend if they had an accounting profit, so the company might have had the cash flow, the cash and the franking credits, but if its assets had fallen in value (as happened during the GFC) it couldn’t pay a dividend. This is no longer the case. This change in legislation will give companies greater flexibility with dividend payments. Since this change was implemented we have seen several LIC’s pay a steady stream of dividends which in my view has helped to narrow the discount to NTA in the last two years.

The second significant structural change is the reform of the financial planning industry. From 1 July 2013, commissions paid to financial planners by providers of managed funds will be banned on new allocations. This will remove a significant impediment for financial planners looking at LICs or other investment products listed on the stock market, such as Exchange Traded Funds. LICs don’t pay trailing commissions. For years financial planners have had a significant financial incentive to recommend managed funds, and thus LICs have not fully benefited from the significant growth in the funds management industry. Finally, the playing field will be level. In our business at WAM, we are already seeing an increased level of interest from financial planners in LICs with our funds under management increasing from $300 million to $700 million over the last 12 months.

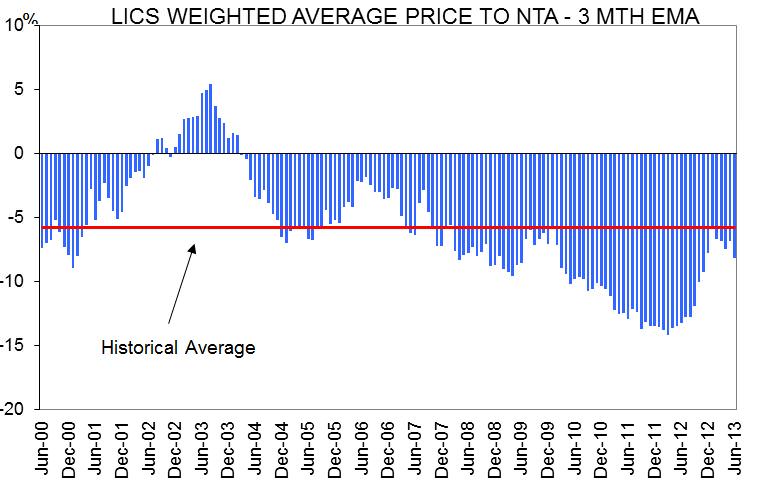

Source: Patersons Securities. EMA = Exponential moving average.

Since these changes were first discussed, the discount to NTA of a number of LICs has decreased. Currently the average discount for the sector is 8.4%. The above chart from Patersons Securities highlights the experience since 2000. To date in 2013, we have seen two successful LIC floats being the Naos Emerging Opportunities Fund and the Watermark Market Neutral Fund. These are the first LICs to make initial public offers since the GFC, further evidence that interest is returning to the sector. I believe that the momentum gained in recent years has scope to continue given the thematics for the sector.

Chris Stott is Chief Investment Officer and Portfolio Manager at Wilson Asset Management.