Brace yourself! If only an ‘amygdala hijack’ came with this warning. In 1995, psychologist Daniel Goleman coined the term to describe what happens when individuals experience an immediate, intensified emotional response that short-circuits the rational, decision-making part of the brain. In this moment, our limbic brain (the emotional hub) takes centre stage, bypassing our cerebral filtration system and generating an action plan without rhyme or reason. The good and bad news: amygdala hijacks are indiscriminate, meaning they can and do affect us all. But they are especially pervasive in the stock market, where whipsawing prices beget sudden heightened emotions.

So, what happens when our feelings gain the upper hand? In the heat of the moment, a disproportionate emotional response can have untold financial repercussions. While we cannot forecast the timing of an amygdala hijack, we know it may loom on the horizon. However, by cultivating better behavioural habits and implementing routine, positive interventions, we can minimise its severity and swing our emotions in our favour.

The chasm between investment returns and investor returns

Empirical evidence demonstrates that most investors underperform their investments. The case of Peter Lynch of Fidelity Magellan is a classic example. From 1977 to 1990, the fund generated an average annualised return of 29.2%, while investors in the fund reportedly averaged ~7%. This suggests something that caused investors to make ill-timed entries and exits and let their returns slip, landing them on the wrong side of an enormous delta. Whether it was a gap between their perceived and actual tolerance for uncertainty; an unchecked appetite for risk; or their proclivity to invest when prices were high and exit when they were low, it boils down to a temperamental differential. In lieu of an appropriate anchor to reel them in, investors surrendered to feelings that were urgent-but-fleeting, ignoring their better judgment and taking the expressway to short-change their future selves.

In this example, an invisible psychological divide emerges between investors such as Lynch and the rest of the fund’s investors. While many succumbed to price swings, the fund’s performance demonstrates that calibrating one’s emotions in accordance with the positions one holds can bear significantly on an investor’s outcomes. This gap between investment return and investor return proffers an invaluable lesson: while stock selection is important, the successful investor’s edge lies in synchronising their portfolio make-up with their individual emotional make-up—or else, history demonstrates that a shaky mindset will not survive a well-chosen but volatile stock or fund. To borrow from psychologist Alfred Adler, it may be argued that although fixation is an inevitable and universal experience for investors, what they fixate on is theirs to choose – and can have a decisive impact on their outcomes. Thankfully, like a muscle or a habit, fixation can be optimised.

Staircase versus ‘rollercoaster’

This is why we choose to concentrate on the dividend-growth staircase of our companies rather than fixating on short-term, often erratic gyrations of share prices. We have developed a skillset to identify and predict companies who can grow their dividends sustainably at rapid rates for the long arc of time. While share price can and will diverge from an underlying company’s fundamental business performance from time to time, engendering the possibility of occasional amygdala hijacks, a focus on the rapid growth rates of these dividend increases parses the investment journey into smaller, manageable increments while providing helpful clues to the company’s fundamentals.

This graphic illustrates the stark experiential differences between the investor-friendly dividend-staircase journey versus the more volatile and erratic nature of the share price ‘rollercoaster’. Source: Roper Technologies Inc (NASDAQ: ROP) company filings and DivGro research. Roper Technologies Inc has been held in the DivGro Fund since inception.

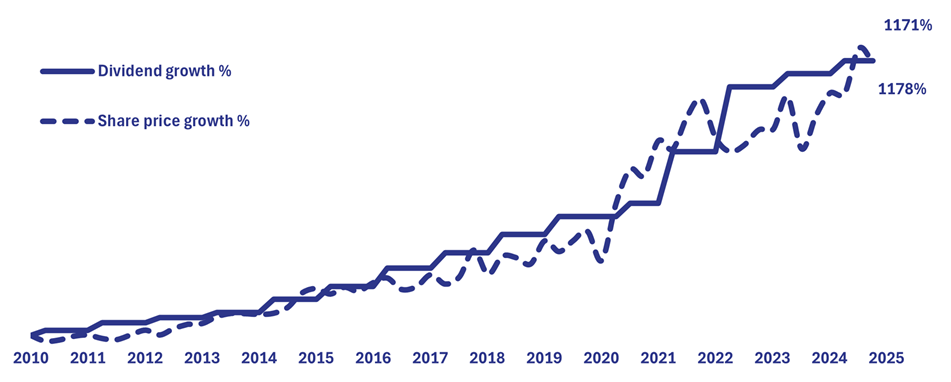

While rates of change in dividends and share prices have been shown to ultimately synchronise, they traverse distinct paths with inherently obverse emotional experiences. The fast-rising dividend-growth staircase provides the opposite of an amygdala hijack. It offers microdosed anticipation: regular boosts of positive data points that fortify investor mindsets and prime us for long-term success. Plus, unlike other metrics, which may be massaged, dividends are paid in cash and are extremely telling; cut or increased, consistent or sporadic, fast or slow growing, they open a window into a company’s health span. If volatile prices can engender our fight-or-flight response, think of rapidly rising, consecutive dividend-growth updates as brain fertilisers, arming investors with enough emotional scaffolding to stay the course and enjoy the benefits of compounding.

This graph exhibits the relationship between the rate of dividend growth of Lowe’s Companies and the rate of growth of its share price. Lowe’s Companies (NYSE: LOW) has been held in the DivGro Fund since inception. Source: Company filings and DivGro research

This approach has roots at MIT, where Professor Myron Gordon and his team demonstrated that over time and at points in time, where the dividend goes, share price follows. For example, if one can identify a company that will raise its dividend annually at 13% for the long arc of time, one should expect its share price to appreciate at an approximately commensurable rate.

A further psychological innovation, which we developed, underlies this model. If you shift investor focus to this dividend-growth progress, by regularly highlighting entitlements, receipts and rapid increases, this highly original methodology can buoy investors and empower them to focus on the fundamentals, dramatically upleveling their likelihood of holding onto their investments long enough to see them compound. It is a unique investment playbook with a one-two punch: dividend growth provides both an analytical sieve to identify excellent companies and a highly effective psychological keel.

Why psychology tips the scales

What happens if we don’t troubleshoot our emotions? Given it is harder to quantify, investor psychology is largely overlooked even though it is critical to one’s success or failure in the stock market. It is easier to blame bad selection, bad timing, or bad luck than to consider the correlative relationship between emotional resilience and positive feedback. Yet countless real-life examples evidence that the two work in lockstep and have profound impacts on our outcomes and abilities to correct a stress-induced response.

Take Uber. To reduce rider discomfort, Uber implemented the Goal Gradient Theory within its app. Originally tested on mice in a maze, the theory posits that the closer we are to a goal, the more motivated we become to reach it – and the less we are inclined to ditch the app, hail a taxi, or agonise over whether our ride will arrive at all. So, Uber introduced the animated car feature so riders can track the incremental progress of their car on its way to them, making the experience more palatable, providing a degree of certainty, and reducing the long-term into short-term intervals. It’s a low-stakes example of the ways positive intervention, repeated consistently, maximises durability – a sticking point that is magnified in investing, where individuals stand to be rewarded handsomely in the outer years but tend to trade in and out of holdings prematurely.

French pharmacist and psychologist Émile Coué’s work echoes the efficacy of positive intervention. Born in 1857, Coué earned a degree in pharmacology, eventually working in an apothecary. There, he had an epiphany while interacting with patients: if Coué helped them to expect to recover, his patients would respond better to their medication. So, he developed the habit of attaching positive notes to his prescriptions (what we now call positive affirmations), recognising that wherever attention is focused repeatedly, it tends to materialise – and it worked. Analogous to a dividend-growth focus, Coué mobilised what mattered so his patients could tune out the rest, lowering the decibel on ancillary anxieties to give his patients a better chance to heal.

Still, naysayers may believe emotion has no place on Wall Street. They should cast their minds to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, where Simone Biles (history’s most decorated gymnast) was set to become the first woman to win consecutive titles in the all-around in 53 years. She hadn’t lost an all-around since 2013. Suddenly, she withdrew from the competition due to the ‘twisties’, a phenomenon wherein gymnasts lose spatial awareness mid-air due to a disconnect between mind and body. In the most decisive moment of her career, Biles’s mind failed her body when she needed it most. Her skills, talent and experience were no match for an amygdala hijack, even though Biles was at the top of her game. Her story is a powerful reminder that the most climactic moments can expose our fragilities should we choose to ignore them – or provide an opportunity to succeed if we develop the habit of mastering them instead.

Jen Nurick and Josh Veltman work across Investor Relations and Communications at DivGro. This information is not investment advice or a recommendation to invest. It is general information only and does not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation or needs of any prospective investor.