As a fund manager, we like to talk about the stocks we hold: what the companies do, why they look attractive and how they fit with our investment philosophy. Stock picking is key to our investment philosophy. Outperforming over the long term, however, does not solely depend on the stocks you pick. It also depends on how you weight those stocks in your portfolio.

While there are many ways to construct a portfolio, our preferred method is to weight stocks so that those we think have lower downside risk, both in absolute terms and relative to the potential upside, have a higher weight.

This article explains why we choose to do this: exploring some theoretical underpinnings in the Kelly Criterion; explaining how it might apply to portfolios; some practical limitations in the real world and how we use this approach in the Allan Gray Australia Funds.

Lessons from a coin toss

Suppose we play a game in which we toss a fair coin (50% chance of heads or tails) once a month for 20 years, a total of 240 coin tosses.

We start with $100 in the bank and, for each coin toss, we are allowed to bet as much of our current pool of funds as we would like.

For every $1 we bet, if the coin toss comes up heads, we win exactly the amount we staked as profit, so we end up with $2 in total. If the coin toss comes up tails, we lose half of our stake and would end up with 50 cents.

Sounds like a pretty good game to play, doesn’t it? Even odds of winning and losing, but the amount you win is double the amount you lose. So why not bet everything you’ve got? After all, on average, for each dollar you bet, you will end up with $1.25 (there is a 50% chance of winning $1, and a 50% chance of losing 50c). The more you bet, the better, right?

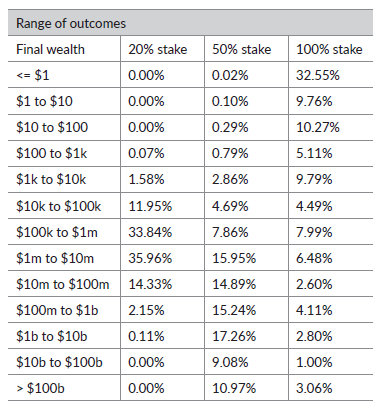

If things go your way and a lot of heads come up, you could end up as rich as Warren Buffett. Indeed, there is around a 3% chance that your initial $100 will be worth more than $100 billion after 20 years.

Unfortunately, if there are a lot of tails in the series of coin tosses, this strategy fares badly. In fact, there is about a one-in-three chance that you will have less than $1 left after 20 years, and a greater than 50% chance you will end up with no more than the $100 you started with.

Suddenly, betting the farm on every coin toss seems risky. It turns out that the average return is distorted by a small minority of outliers.

What about the other extreme? If you bet zero on each coin toss, you will end up with $100 at the end of 20 years. That’s a good way to limit the downside, but $100 might only buy a couple of decent hamburgers in 20 years – probably not a sensible retirement strategy.

The Kelly Criterion

It was American physicist, John Kelly, who figured out the optimal strategy for the coin toss scenario, as well as far more complicated examples, in the 1950s.

His work established the so-called ‘Kelly Criterion’, which describes the size of the stake that maximises the expected geometric growth rate of your wealth over time or, equivalently, the amount of money you will have at the end of a given period.

In the case of the coin toss game, the optimal stake at each toss of the coin is exactly half of what is in your wallet. Following this strategy, the chance that you will end up with less than the $100 you started with is only 0.4%, compared to the one-in-two chance with the all-in strategy. There is a greater than 50% chance of amassing more than $100 million at the end of 20 years, and an 11% chance of amassing more than $100 billion! Position sizing changes the payoff profile dramatically.

What you sacrifice is the tail-end chance of earning astronomic returns (trillions and higher) with a run of extreme luck in the all-in strategy, but most people would regard the range of possible outcomes as very attractive.

We simulated playing this game a million times, with stakes of 20%, 50% and 100% of our wallet at each stage. You can see the results in the table below.

While it will not always be true that allocating a 50% stake gives the best outcome, in our simulation, this allocation gave a better outcome than placing a 20% stake roughly 95% of the time, and a better outcome than placing a 100% stake over 99% of the time.[1]

One striking aspect about following the Kelly Criterion is that it leads to concentrated bets. In the above game, a 50/50 bet where you lose half your stake if you are wrong but win the entire amount you stake if you are right, dictates betting 50% of your wallet on each bet.

To take another example, for an even money bet (which will return exactly the amount you staked as profit if you win but will cause you to lose the full amount staked if you lose), and where the odds of success are 60%, the Kelly Criterion suggests betting 20% of your wallet.

Applying the Kelly Criterion to an investment portfolio

If we think through the lens of the Kelly Criterion, the process of a fund manager selecting stocks is very similar to playing a succession of games like those in the example.

When fund managers think about how to construct a portfolio, they can choose different ways to size their positions. Some of these include:

At Allan Gray, we tend to construct our portfolios using option 3.

This may seem counterintuitive. Why not use option 2 and weight more to the stocks that have greater upside potential?

The Kelly Criterion shows us why that may not be optimal. If the downside is large, or the probability of that downside is large, then Kelly would suggest investing a small fraction of your capital, because repeating this across many stocks over many years would result in a suboptimal outcome.

By using option 3, we essentially focus on how much we could lose relative to how much we could gain. If we think the downside is small in both relative and absolute terms, we will consider allocating a larger weight. And knowing that even getting 60% of our calls correct is probably quite a good outcome, the probability that the investment increases or decreases in value may be near equal.

Practical limitations and general lessons

While this is all nice in theory, the real world is messier than the idealised example we use to illustrate the Kelly Criterion. For example:

- You cannot place the identical trade successive times

- Many investments are made in parallel

- There are friction costs, such as trading fees and tax, that will eat into returns

- The stocks we invest in can be correlated, which changes the portfolio’s risk profile

- News flow can change the upside and downside potential continuously

- The opportunity to buy a stock at your ideal price may not last long enough to build your position

- There may be self-imposed constraints that try to reduce some measure of risk, e.g. not having any individual stock be greater than a certain weight in the portfolio

- It is usually not possible to precisely know the probability of success in advance.

The theory provides a few useful lessons

Some applications for portfolio construction include:

- Consider having a more concentrated portfolio. Application of the Kelly Criterion lends itself to larger weights than you might expect. This is not the way most fund managers behave; most are overly diversified, perhaps in part because incentive structures are not aligned to reward the potential volatility of such a strategy.

- Sense-check position sizes. When viewing our portfolio, we always ask ourselves: have we got a greater weight in stocks that have a lower downside risk – both absolute and relative to upside – and, if not, what can we do about it? Restraint can be better than regret.

- Hit rate (the number of stocks in a portfolio that outperform) isn’t everything. You can outperform with a low hit rate (providing the upside of each outperforming investment is large) and you can underperform with a high hit rate (if, for example, your position sizing does not work out).

In summary, maximising the chances of long-term outperformance depends on the position size, as well as the stocks that we pick. Our contrarian investment strategy helps us with stock selection, but the somewhat ‘hidden art’ of portfolio weighting contributes no less to how we perform in the long term.

[1] For some of the details behind this simulation, see this article from the CFA Institute.

This version was first published on 10 February 2023.

Dr Justin Koonin is an Analyst at Allan Gray, and is also a board director, philanthropic adviser, academic, community advocate on health and human rights, and holds several expert roles with the World Health Organization in global health.

Additional contributors: Simon Mawhinney, Managing Director and Chief Investment Officer; Dr Suhas Nayak, Analyst and Portfolio Manager; and Julian Morrison, Investment Specialist.