Australia’s fertility rate has dropped to a historic low level of 1.5 births per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1 required to maintain a stable population. One factor affecting fertility decisions may be the availability of childcare, as it helps reduce financial and logistical barriers to child-rearing. Grandmothers are a vital source of informal childcare support for many families. However, policies that increase the labour market participation of older women, such as raising the Age Pension eligibility age from 60 to 67, may reduce grandmothers’ availability to provide childcare.

This note investigates an underexplored trade-off in policy design: how measures encouraging work among the older population can unintentionally impact their offspring’s fertility rates. Specifically, it investigates how changes to Age Pension eligibility age may have reduced grandmothers’ availability for childcare, subsequently influencing their daughters’ fertility decisions. Given Australia’s low fertility rates and aging population, this note highlights the trade-offs in designing policies that encourage labour force participation among older people without negatively affecting fertility.

Our results show:

- The increase in the pension eligibility age delayed grandmothers’ retirement, increasing their employment rate from 25% to 36%, and hours of work by 3.9 hours per week.

- Having a grandmother who qualifies for the pension based on her age increases the likelihood that her daughter will have a child, from 69% to 73.5%, and increases the average number of children per woman from 1.47 to 1.56. This effect on the average number of children per woman is comparable to the impact observed with the introduction of paid parental leave policies.

- Among daughters in lower-wealth households and those with lower educational attainment, grandmother’s pension eligibility had a larger effect on fertility, suggesting that access to grandparental childcare may play a greater role in fertility decisions for these groups.

- The increase in pension eligibility age reduces grandmothers’ ability to provide childcare by keeping them in the labour market longer. Grandmothers who are age-qualified for the pension are more likely to provide childcare, whereas those who work longer hours are less available for caregiving.

Fertility decisions are shaped by a range of factors, often reflecting a trade-off between career prospects and family planning. Support systems/arrangements, such as free or grandparental childcare, play a crucial role in easing the financial burden of child-rearing. The recent Productivity Commission report on early childhood education and care underscores the importance of grandparental childcare, highlighting its spillover effects: caring for grandchildren can act as a barrier to working for grandparents and lead them to reduce their working hours to provide this support. However, less attention has been paid to the reverse dynamic: policies aimed at increasing labour market participation among older individuals may reduce the availability of grandparental childcare, potentially impacting fertility choices among their offspring.

Census data reveal that grandparental care is predominantly provided by women, with the share of women caring for other children — likely their grandchildren — peaking around their age pension (AP) eligibility age. This pattern underscores the trade-offs they face between caregiving and labour market participation.

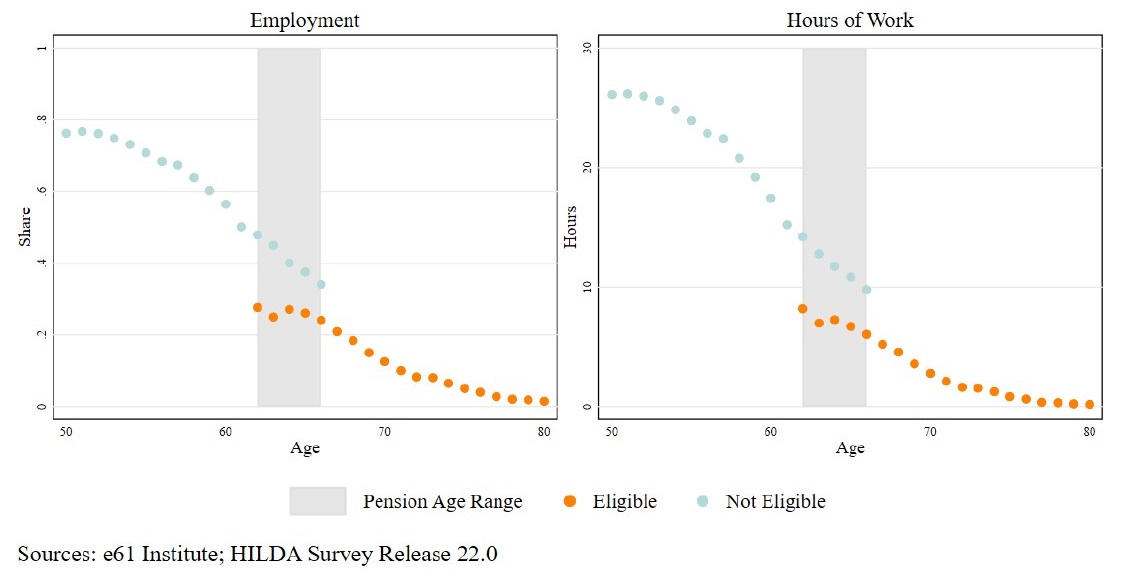

Figure 1: Effect of age pension eligibility on women’s labour market outcomes by age pension eligibility

What is the effect of pension reform on the labour supply of older women?

The Australian AP reform has gradually raised the minimum age for AP eligibility for women from 60 to 67, increasing by six months every two years since July 1, 1995, to decrease the fiscal cost of the aging population. Using data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, Figure 1 illustrates that women eligible for the pension based on their age1 have lower employment rates and work fewer hours per week compared to those who are not eligible. However, this raw comparison does not account for the differences between cohorts, which are influenced by the gradual implementation of the reform. For example, consider two women born in June 1952 and June 1954, respectively. The woman born in 1952 would qualify for the pension at age 65, while the woman born in 1954 would qualify at age 66. As a result, when these women are 65 years old, one becomes eligible for the pension based on age, while the other would still be ineligible. These differences in outcomes by pension eligibility reflect not only the staggered rollout of the policy, but also the varying social and economic contexts experienced by different birth cohorts. As a result, women from different cohorts may have been influenced by varying economic, social, and labour market conditions, potentially confounding the observed relationship between pension eligibility and employment outcomes. Therefore, it is important to control for these differences.

To address this, we control for observed and unobserved, time-invariant factors affecting labour market outcomes, such as cohort-specific differences.2 After accounting for individual differences, our analysis shows that the employment rate among grandmothers eligible for the pension is 25%, compared to 36% for those who are ineligible. Additionally, eligible grandmothers worked 3.9 fewer hours per week. These results suggest that the Australian pension reform was effective in keeping older women in the labour market, achieving its intended policy goal.

What is the effect of mother’s age pension eligibility on the fertility of daughters?

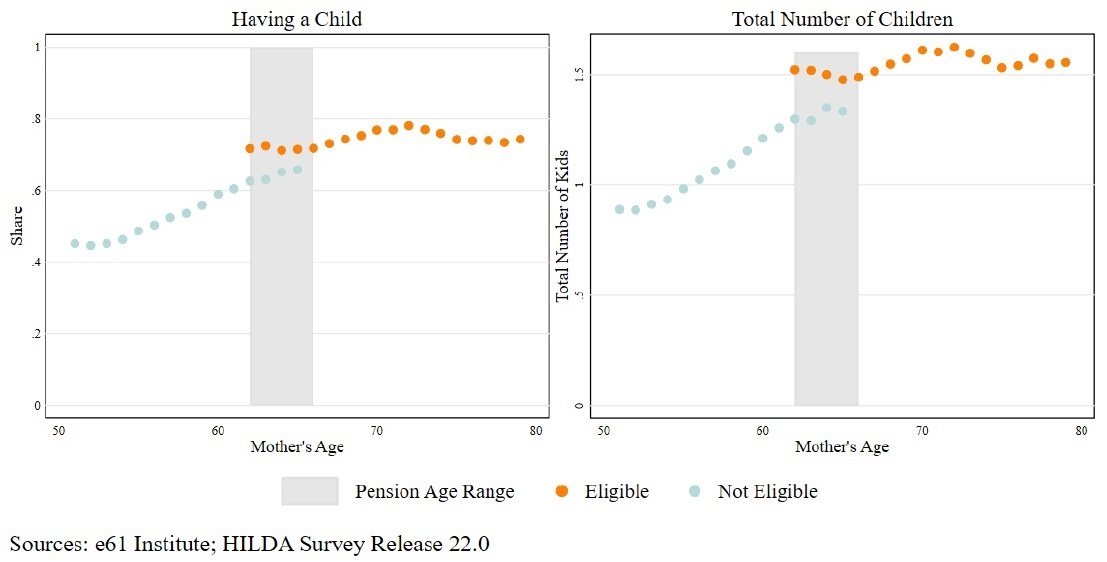

Women whose mothers are eligible for the AP based on their age are more likely to have children and have more children on average, compared to women whose mothers are of similar age but ineligible (Figure 2). However, this association may also reflect cohort differences, as women whose mothers qualified for AP earlier belong to older cohorts that may have different norms, socioeconomic conditions, and characteristics.

Figure 2: Effect of mother’s age pension eligibility on fertility of daughters by age pension eligibility

After taking into account individual, age- and year-specific factors, we find that having a mother eligible for AP increases the probability of having a child from 69% to 73.5% and increases the average number of children from 1.47 to 1.56. These effects are more pronounced for women in lower-income households and those without a university degree, suggesting that grandparent support is likely more important for women facing greater financial or social constraints.

The observed impact of grandmother’s AP eligibility on the average number of births is around 4.5%, comparable to the effect of introducing paid parental leave policies, which increased the average number of births by 5% through improved childcare support and reduced financial burdens.

How does grandmothers’ pension eligibility affect their childcare provision?

The most plausible mechanism linking grandmothers’ AP eligibility to their daughters’ fertility is the availability of informal childcare. Pension reform delayed grandmothers’ retirement, which could have reduced their ability to provide childcare to their grandchildren. Our results confirm this, showing that grandmothers eligible for pension based on their age are more likely to provide childcare, with the proportion increasing from 59.4% to 63.4%. Additionally, the frequency of care increases with their pension eligibility.

We examine grandmothers’ hours of work to understand whether this increase in childcare provision is driven by the reform’s effect on grandmothers’ labour market participation. Our analysis shows that once we account for the hours worked by grandmothers, the effects of pension eligibility on the provision and frequency of childcare become smaller and less pronounced. Moreover, grandmothers who work longer hours are less likely to provide care for their grandchildren and tend to do so less frequently. Overall, our findings suggest that pension eligibility increases grandmothers’ availability for childcare by reducing their labour market participation.

These findings suggest that pension reforms that increase the eligibility age can have unintended intergenerational consequences on fertility. While such policies aim to improve fiscal sustainability and labour market outcomes, they may inadvertently reduce the availability of grandparental childcare, influencing daughters’ fertility decisions. This highlights the importance of designing policies that balance the needs of an aging population with support for young families.

1 Throughout this note, pension eligibility refers only to age-based eligibility, excluding income, assets, or residency criteria.

2 We also include year-fixed effects and potentially time-varying characteristics such as education, region, etc.

Dr. Pelin Akyol is an Economist and Research Manager at e61 Institute. Professor Kadir Atalay is a Postgraduate Research Coordinator (Economics) at the University of Sydney. The the full report, including references, appendices and disclaimers can be accessed here.