Since its origination in the United States in the early 1970s, indexing as an investment strategy has grown tremendously, to the point that according to Morningstar, assets in US-domiciled index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) accounted for 38% of equity and 19% of fixed income funds as of year-end 2014. In Australia, 6.6% of total assets under management are now index funds and ETFs as at the same date. Broader industry surveys point to indexing representing 18% of assets (Rainmaker data, 31 December 2014).

An indexed investment strategy seeks to track the returns of a particular market or market segment after costs by assembling a portfolio that invests in the same group of securities, or a sampling of the securities, that compose the market. Indexing (or passive) strategies use quantitative risk-control techniques that seek to replicate the benchmark’s return with minimal expected deviations (and, by extension, with no expected positive excess return versus the benchmark). In contrast, actively managed funds, either fundamentally or quantitatively managed, seek to provide a return that exceeds a benchmark. In fact, any strategy that operates with an objective of differentiation from a given market capitalisation-weighted benchmark can be considered active management and should therefore be evaluated based on the success of the differentiation.

Can investors consistently pick winning funds?

Two critical questions for investors in actively managed funds are: “Do I have the ability to pick a winning fund in advance?” and “Will the winning fund continue to win for the entire life of my portfolio?” In other words, can an investor expect to select a winner from the past that will then persistently outperform in the future? Academics have long studied whether past performance can accurately predict future performance. More than 40 years ago, Sharpe (1966) and Jensen (1968) found limited to no persistence. Three decades later, Carhart (1997) reported no evidence of persistence in fund outperformance after adjusting for both the well-known Fama-French three-factor model (that is, the influence of fund size, fund style and momentum). Carhart’s study reinforced the importance of fund costs and highlighted how not accounting for survivorship bias can skew results of active/passive studies in favour of active managers. More recently, Fama and French (2010) reported results of a separate 22-year study suggesting that it is extremely difficult for an actively managed investment fund to regularly outperform its benchmark.

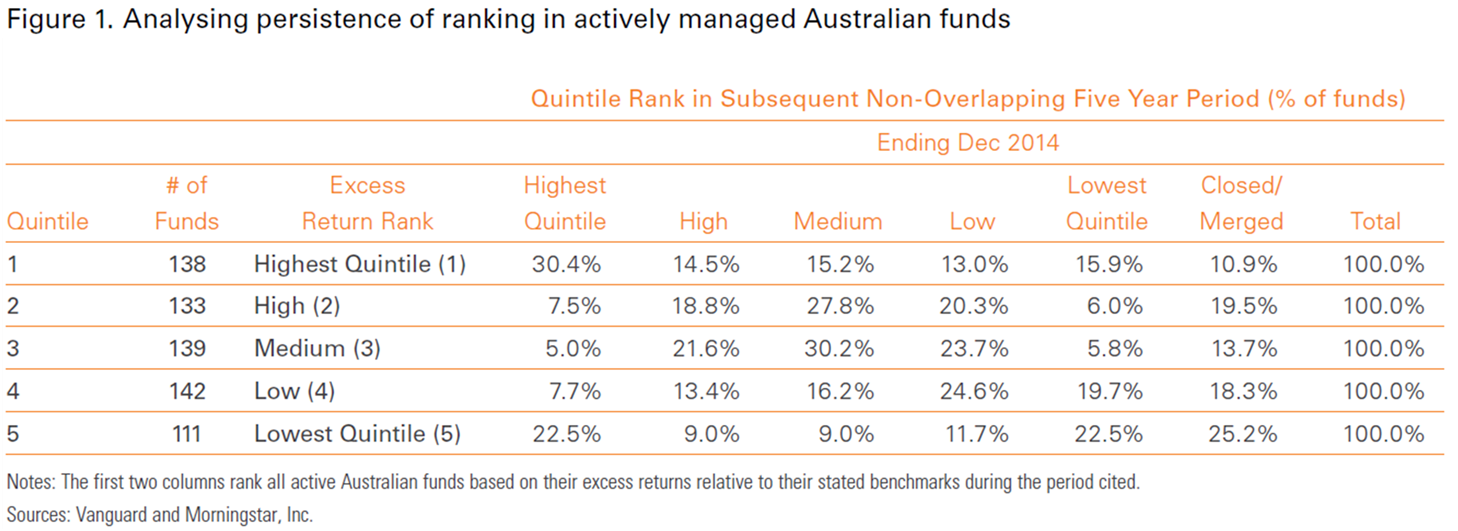

To analyse consistency among actively managed funds, we ranked all eligible Australian funds in terms of excess return versus their stated benchmarks over the five years ended 2009. We then divided the funds into quintiles, separating out the top 20% of funds, the next-best-performing 20% of funds, and so on. We then tracked their excess returns over the following five years (through December 2014) to check their performance consistency. If the funds in the top quintile displayed consistently superior excess returns, we would expect a significant majority to remain in the top 20%. A random outcome would result in about 20% of funds dispersed evenly across the five subsequent buckets (that is, if we ignore the possibility of a fund closing down).

Figure 1 shows the results for Australian funds do not appear to be significantly different from random. Although about 30% of the top funds (42 of 138) remained in the top 20% of all funds over the subsequent five-year period, an investor selecting a fund from the top 20% of all funds in 2009 stood a 27% chance of falling into the bottom 20% of all funds or seeing his or her fund disappear along the way. Stated another way, of the 663 funds available to invest in 2009, only 42 (6%) achieved top-quintile excess returns over both the five years ended 2008 and the five years ended 2014.

The subsequent performance of funds that were in the bottom quintile in 2009 was revealing. Fully 25% of the 111 funds were liquidated or closed by 2014, and 23% remained in the bottom quintile, while only 32% managed to ‘right the ship’ and rebound to either of the top-two quintiles. Indeed, persistence has tended to be stronger for previous losers than previous winners.

This high turnover with respect to outperformance and market leadership is one reason the temptation to change managers because of poor performance can simply lead to more disappointment. For example, Goyal and Wahal (2008) found that when US institutional pension plans replaced

underperforming managers with outperforming managers, the fired managers outperformed the managers hired to replace them by 0.49% in the first year, 0.88% over the first two years, and 1.03% over the first three years.

Impact of market cycles on results of actively managed funds

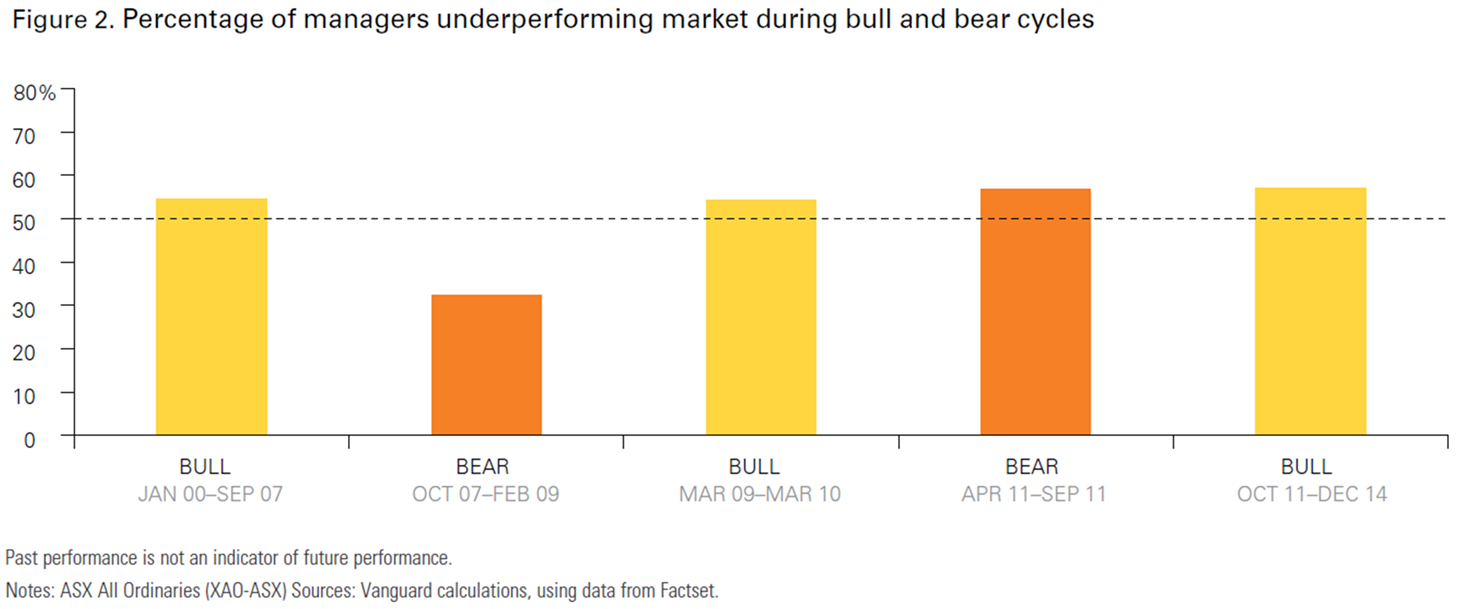

One perspective with respect to market cycles is the performance of actively managed funds during bear markets (index down by a cumulative 20%. A bull markets is the converse). A common perception is that actively managed funds will outperform their benchmark in a bear market because, in theory, active managers can move into cash or rotate into defensive securities to avoid the worst of a given bear market.

In reality, the probability that these managers will move fund assets to defensive stocks or cash at just the right time is very low. Most events that result in major changes in market direction are unanticipated. To succeed, an active manager would have to not only time the market but also do so at a cost that was less than the benefit provided. Figure 2 illustrates how hard it has been for active fund managers to outperform the broad ASX accumulation index. In one of two bear markets and three out of three bull markets, the average mutual fund underperformed its stated benchmark. To win over time a manager must not only accurately time the start and end of the bear market but select winning stocks during each period.

The challenge facing investors is to correctly identify those managers who they believe may outperform in advance and stick with them through good times and bad. Finally, when deciding between an indexed or actively managed strategy, investors should not overlook the advantages in portfolio construction that well-managed indexed strategies bring to bear.

Sheunesu G. Juru is a Credit Research Analyst and Jeffrey Johnson is Head of Investment Strategy Group Asia-Pacific at Vanguard Investments Australia. This article is general in nature and readers should seek their own professional advice before making any financial decisions.